Corridor Through the Mountains

Smith's Clove: Wartime Line of Communication and Passageway for the Continental Army, 1776-1783

Richard J. Koke

[Editor's Note: Richard J. Koke authored a series of five articles that appeared in Volumes 19 -23 of the OCHS Journal between 1990 and 1994. These articles will be presented in multiple sections over the next few years.]

Part I:

The Country and Precinct

Chapter 3:

The Clove Road

The lifeline that ties the valley together and connected its scattered farms and dwellings was the Clove Road which traversed the entire corridor and had been laid out along the line of an earlier native trail by the redoubtable Charles Clinton of Little Britain, surveyor of the Cheesecock Patent. At one point in his noted Field Book of the patent survey he began in 1735 , Clinton specifically made mention of "an indian path through ye clove to Ramapo."

In its rudimentary state it was little more than an obscure trail which Clinton, describing the path between Ramapo and Nathaniel Hazard's land at Highland Mills, called "scarce noticeable it is so seldom used." By the midcentury, however, the influx of settlers who came to live amid the snakes and Wild beasts, mostly from Long Island, brought an improvement, but travel was not easy. From a scarce noticeable trail, it developed during the next two decades into a "horse path" and wagon way that was kept in what could be considered tolerable repair by local property owners under the prodding of road commissioners and precinct overseers.

In 1761, three years before the valley became Cornwall precinct, Jeffery Amherst, fresh from his conquest of French Canada, spent eleven hours on horseback traveling thirty-two miles from Coldenham to the Sidman house in the lower valley, most of it through the Clove, and he made note that the road was "very stony and narrow" but could "be made very passable." But even with improvements made by the American military to facilitate army use during the Revolution, it remained at best only "a poor common road" to the end of the century.

From Suffern north, it followed present Routes 59 and 17 through Ramapo, Sloatsburg, Tuxedo and Southfields to Arden where, descending to the Ramapo near Arden Valley Road, it crossed to the east shore and continued through the Harriman estate for four miles alongside and east of the New York Thruway to Harriman Interchange (Exit 16), where it turned northwest, passed behind Woodbury Common and into the line of Turner Road and Route 32, which it then followed through Central Valley, Highland Mills, Woodbury Falls and Woodbury Valley to Mountainville where it crossed Moodna Creek and emerged into the New Windsor countryside on its way to Newburgh.

For much of the way, with old turnings and twistings straightened, the road is still in use as a heavily traveled thoroughfare, but within the Harriman property it exists as a private country road. In a few places such as along Woodbury Road (old Route 32) in Woodbury Valley one can still experience something of its former bucolic state. In another place, northwest of Harriman Interchange and extending toward Woodbury Common, the road is abandoned and has reverted to a primitive state in dense woodland, bringing to mind Clinton's comment of two centuries earlier that the pathway was barely noticeable; and one can visualize something of what the road must have been when Washington and his generals rode through the mountain wilderness.

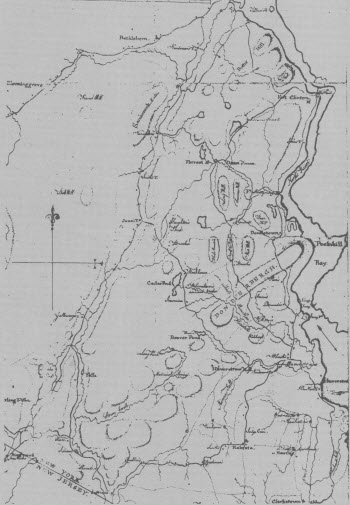

The course of the highway was surveyed and was meticulously plotted on a number of wartime charts now in the New York Historical Society prepared by Robert Erskine, Geographer General of the Continental Army, and his assistants for the cartographic file of Continental headquarters, which are of inestimable value in depicting natural valley features such as "The Torn" at Ramapo and the "Falls" of the river at Tuxedo, along with creeks and buildings and names of occupants along the road.

Map of West Point and the Country West of the Hudson River, 1778-79. Detail of a manuscript map drawn by Robert Erskine (1735-1780), Geographer General of the Continental Army, owned in 1933 by Erskine Hewitt of Ringwood, New Jersey. An identical map is in the Division of Maps, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. This chart delineates the Highland country between the Hudson River, at the right, and the Clove Road, at the left, passing through the Clove from Suffern's Tavern above the New Jersey line to Murderers (now Moodna) Creek below New Windsor. Erskine shows the locations of six of the seven Revolutionary War taverns which stood along the Clove highway.

Map of West Point and the Country West of the Hudson River, 1778-79. Detail of a manuscript map drawn by Robert Erskine (1735-1780), Geographer General of the Continental Army, owned in 1933 by Erskine Hewitt of Ringwood, New Jersey. An identical map is in the Division of Maps, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. This chart delineates the Highland country between the Hudson River, at the right, and the Clove Road, at the left, passing through the Clove from Suffern's Tavern above the New Jersey line to Murderers (now Moodna) Creek below New Windsor. Erskine shows the locations of six of the seven Revolutionary War taverns which stood along the Clove highway.

What is clearly evident in a perusal of the maps is that the more extensively settled region during the war was Upper and Lower Smith's Clove, where diverse families erected their homes and where evidence of more settled life is discernible in the presence of Smith's mill at Monroe, Earl's at Highland Mills, two grist mills on the descent of Woodbury Falls, and lawyer Smith's grist mill at Mountainville.

The key to the military mobility in the Clove that was engendered by war centered on a network of lateral side roads that branched to east and west at Sloatsburg, Harriman, Central Valley, Highland Mills, and Woodbury Clove and facilitated movement into and out of the valley and allowed communication with New Jersey, the river forts, and the hamlets and villages in the Orange and Ulster backcountry for the militiamen who were constantly called upon to succor the Highland's posts.

Those leading towards the river were little more than lonely trails interlocking with others that made their ways through the wilderness to Haverstraw and mountain settlements at Queensboro and Doddletown, the Forest of Dean, and to West Point and a few landings on the Hudson.

One of the most important was the ten-mile-long footpath that branched from the Clove Road at June's Tavern at Harriman and crossed the mountains to Haverstraw by way of Slaughter's Pond (now Forest Lake) and the Cedar Ponds (now Lake Tiorati). Charles Clinton referred to it as part of "Ye Road from Goshen to Haverstraw," and later frequent mention was made to it in testimony delivered in 1785 at the proceedings held at Chester to determine the disputed boundaries of the Cheesecock and Wawayanda patents. Weather-beaten inhabitants who were long resident in the county deposed at the time that the path was the only direct route through the mountains that connected Smith's Clove with the river settlements in lower Orange where the courts were held; otherwise, those contemplating the arduous journey would have to travel down the Clove to Suffern to make the circuitous turn into southern Orange at the Point of the Mountain.

One, recalled it as an "ancient path" that went back nearly half a century - bringing it back to Charles Clinton's day, or earlier; another, that the early settlers approaching from Haverstraw first spied the Clove from the path; and another, that it was a "hard" ride between Haverstraw and June's, and travelers could consider themselves lucky if they got across the mountains by nightfall, at a time when four days could be spent in travel alone making the round trip between Goshen and Tappan.

The course of the rough road was mapped by Erskine and other military cartographers, but with passing time it has become effaced within the forest of the Palisades Interstate Park and the only remaining vestige today is the extreme eastern end where it falls into the line of Willow Grove Road near Thiells.

Part I

Introduction

Clove and Precinct

The Clove Road

The Clove Taverns

Clove Taverns II

Part II

Prelude to War

The Continentals Arrive

Blocking the Clove

In the Midst of Tories

Offensive from the Highlands

The Militia Take Over

The Post at Ramapo

The Reluctant Militia

Holding the Line

An Embarrassing Situation

To Galloway's and Back

The Scotsman's Regiment

September Raid

Prelude for Disaster

Clinton Takes the Highlands

Sidman's Bridge: The Last Holdout

Part III

Introduction

Summer, 1778

A Cogent Appraisal

Villains and Robbers

Part IV

Introduction

Aaron Burr's Ride

March to the Clove

The Barren Clove

Bracing for Attack

Among the Rocks and Rattlesnakes

The Present Interesting Occasion

A Waiting Game

Redeployment

The Continental Road

The Taphouse Keeper's Daughter

The Indian Fighters Appear

March to Morristown

Part V

Introduction

A Fruitless Excursion

Summer at the Clove

A Frenchman's Journey

Pompton Mutiny: Blood in the Snow

Blockhouse in the Clove

The Allies at New Antrim

The Intercepted Messenger

A Questionable Story

What Really Happened

Perils of A Post Rider

New Yorkers at the Clove

Congress' Own Regiment

The Last Garrison

A Man of Passion

Homeless Canadians

The Last March

Part VI

Introduction

The Post at Sidman's Bridge

Marking the Site