Corridor Through the Mountains

Smith's Clove: Wartime Line of Communication and Passageway for the Continental Army, 1776-1783

Richard J. Koke

[Editor's Note: Richard J. Koke authored a series of five articles that appeared in Volumes 19 -23 of the OCHS Journal between 1990 and 1994. These articles will be presented in multiple sections over the next few years.]

Part IV:

1779: A Crucial Year

Chapter 8:

A Waiting Game

On June 21, Washington transferred headquarters from Smith's to the home of Thomas Ellison at New Windsor, where he was better situated to keep in touch with West Point and the troops on both shores of the Hudson. Putnam and the divisions remained in the Clove. The military situation was becoming more stabilized and changing from what it had been earlier in the month, when Sir Henry Clinton was testing the approaches and Washington feared for West Point and Aaron Burr undertook his solitary journey through Smith's Clove to seek succor of St. Clair at Pompton.

WASHINGTON AT THE ELLISON HOUSE, NEW WINDSOR On June 21, 1779, Washington transferred his headquarters from Captain Francis Smith's tavern in the Clove to the stone rivershore home at New Windsor of Thomas Ellison, a wealthy merchant and former colonel of Ulster militia under the Crown, where he remained until his removal to West Point on July 21. The assault on Stony Point was planned here. The building, erected in 1723 or 1724, stood on a bluff overlooking Newburgh Bay at the lower edge of New Windsor village and was variously described - even by Washington himself - as confined, disagreeable, dreary and not large, but, nevertheless, comfortable. It was again occupied by Washington as his headquarters from November 6, 1780, to June 25, 1781. Crayon drawing by Henry Alexander Ogden (1856-1936), based on a painting of the house by John Ludlow Morton (1792-1871), taken shortly before its demolition in the 1830s.

WASHINGTON AT THE ELLISON HOUSE, NEW WINDSOR On June 21, 1779, Washington transferred his headquarters from Captain Francis Smith's tavern in the Clove to the stone rivershore home at New Windsor of Thomas Ellison, a wealthy merchant and former colonel of Ulster militia under the Crown, where he remained until his removal to West Point on July 21. The assault on Stony Point was planned here. The building, erected in 1723 or 1724, stood on a bluff overlooking Newburgh Bay at the lower edge of New Windsor village and was variously described - even by Washington himself - as confined, disagreeable, dreary and not large, but, nevertheless, comfortable. It was again occupied by Washington as his headquarters from November 6, 1780, to June 25, 1781. Crayon drawing by Henry Alexander Ogden (1856-1936), based on a painting of the house by John Ludlow Morton (1792-1871), taken shortly before its demolition in the 1830s.

The British were still at King's Ferry, but nothing was happening. It was a time of waiting as anxiety turned to confidence. Constant attention was given to security and the patrol of roads leading to King's Ferry and Haverstraw. On June 23, Washington ordered Putnam to advance Smallwood's Maryland brigade from the Clove to the Forest of Dean and the other troops were to be held in readiness to march if necessary.

In a letter to his wife, Baron de Kalb offered a vivid picture of campaign life in the wilderness: "Yesterday I made the most wearisome trip of all my life, visiting the posts and pickets of the army in the solitudes, woods and mountains, clambering over the rocks, and picking my way in the most abominable roads. My horse having fallen lame, I had to make the whole distance on foot. I never suffered more from heat. On my return I had not a dry rag on me, and was so tired that I could not sleep."

Even Erskine's young geographers found cause to complain, as when twenty-three-year-old Simeon DeWitt wrote: "I have been cursing the mountains ever since we came to this place because they tire me so much in travelling over them. We have Survey'd nothing but the Paths and Passes on them - I have wore a piece off my toe in Walking so much."

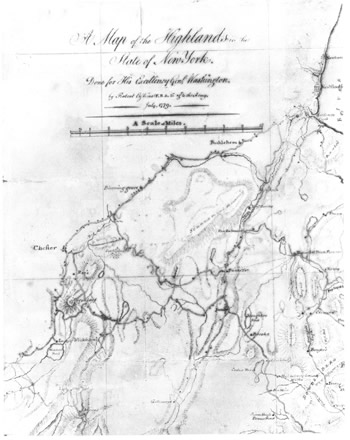

The enterprising activity of the cartographers was reflected in a handsome manuscript map of the Highlands in Erskine's own hand, now in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Dated July 1779 and inscribed as "Done for His Excellency Genl. Washington," the chart is of particular significance as far as Smith's Clove is concerned in its delineation of the camps of Washington's three divisions in the corridor - an important feature first noted in 1993 by Bob McDonald of Clementon, New Jersey, a student of the military camps, in discerning Erskine's use of tent-like symbols to indicate the campgrounds. These locations, otherwise unidentified, clearly coincide with the positions given in General Orders.

A MAP OF THE HIGHLANDS IN THE STATE OF NEW YORK July 1779. Detail from a manuscript map of the Hudson Highlands on both sides of the Hudson River drawn for His Excellency General Washington by Robert Erskine (1735-1780), Geographer to the Continental Army. The detail illustrated centers on the mid and northern area of Smith's Clove and depicts the course of the Clove Road, extending diagonally from Galloway's tavern at Southfields at the bottom center to New Windsor and Newburgh at the upper right. Also shown are the lateral roads leading westward from the Clove to Chester, Blooming Grove and Bethlehem, and eastward to the Forest of Dean, West Point and the Hudson. The now-vanished Haverstraw road, passing through the Palisades Interstate Park and connecting the Clove at June's tavern at Harriman with the settlements in lower Orange (now Rockland) County, is at the lower right. Other roads, not surveyed, are indicated by dotted lines. An important feature is Erskine's delineation in the Clove corridor of the encampments of Washington's three divisions at June's tavern, along Route 32 in Central Valley and on John William Smith's farm in Woodbury Valley below Mountainville. Aside from its preparation for the commander-in-chief, Erskine's map is of interest in its association with Brigadier-General Anthony Wayne, then recently arrived from Pennsylvania. On July 1, 1779, Washington formally assigned him to command the newly-formed corps of light infantry, with confidential instructions to look into the possibility of a surprise attack on the British post at Stony Point, and to acquaint himself with the terrain and state of the enemy garrison. Two days later, pursuant to Washington's order, Erskine wrote to Wayne from New Windsor, transmitting the map with Washington's request "that no Copies whatever be permitted to be taken of it." Bob McDonald, who carefully researched the circumstances of Erskine's chart, offers the interesting commentary that the map may well have been used by Wayne during his planning with Washington of the assault on the British post, and points out that another letter, exactly duplicating the date and content, was also sent to Baron von Steuben, which clearly indicates that at least two charts, presumably identical, were completed by Erskine early in July. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

A MAP OF THE HIGHLANDS IN THE STATE OF NEW YORK July 1779. Detail from a manuscript map of the Hudson Highlands on both sides of the Hudson River drawn for His Excellency General Washington by Robert Erskine (1735-1780), Geographer to the Continental Army. The detail illustrated centers on the mid and northern area of Smith's Clove and depicts the course of the Clove Road, extending diagonally from Galloway's tavern at Southfields at the bottom center to New Windsor and Newburgh at the upper right. Also shown are the lateral roads leading westward from the Clove to Chester, Blooming Grove and Bethlehem, and eastward to the Forest of Dean, West Point and the Hudson. The now-vanished Haverstraw road, passing through the Palisades Interstate Park and connecting the Clove at June's tavern at Harriman with the settlements in lower Orange (now Rockland) County, is at the lower right. Other roads, not surveyed, are indicated by dotted lines. An important feature is Erskine's delineation in the Clove corridor of the encampments of Washington's three divisions at June's tavern, along Route 32 in Central Valley and on John William Smith's farm in Woodbury Valley below Mountainville. Aside from its preparation for the commander-in-chief, Erskine's map is of interest in its association with Brigadier-General Anthony Wayne, then recently arrived from Pennsylvania. On July 1, 1779, Washington formally assigned him to command the newly-formed corps of light infantry, with confidential instructions to look into the possibility of a surprise attack on the British post at Stony Point, and to acquaint himself with the terrain and state of the enemy garrison. Two days later, pursuant to Washington's order, Erskine wrote to Wayne from New Windsor, transmitting the map with Washington's request "that no Copies whatever be permitted to be taken of it." Bob McDonald, who carefully researched the circumstances of Erskine's chart, offers the interesting commentary that the map may well have been used by Wayne during his planning with Washington of the assault on the British post, and points out that another letter, exactly duplicating the date and content, was also sent to Baron von Steuben, which clearly indicates that at least two charts, presumably identical, were completed by Erskine early in July. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The camp of the Virginia division on the Clove Road at the head of the mountain path leading to Haverstraw is shown clustered around June's tavern on ground now altered and traversed by the Thruway and approach roads in the tollbooth area of the Harriman Interchange (Exit 16). The Maryland division, stationed with other units in the center close to Clove headquarters, is shown on both sides of Route 32 in the present business center of Central Valley, extending, roughly, between Dunderberg Place and Roselawn Road near Smith's tavern and the Earl's tavern road head, half-a-mile above. The camp of St. Clair's Pennsylvania division on the farm of John William Smith in Woodbury Valley is shown on the west side of Woodbury Road (old Route 32), extending from the lower end of the valley towards what was later to be Houghton Farm in the mid-valley where lawyer Smith's house was situated. Modern Route 32, which parallels the colonial Clove Road a few hundred feet to the west, passes directly through the campground.

By July 6, all Nathanael Greene could do was to write resignedly from New Windsor: "We are here in a state of inactivity ... Almost as idle as if the season for a Campaign had [not] arrived." Stirling, whose daughter was about to be married in New Jersey, requested a week's leave of absence to attend the wedding at his Somerset home at Basking Ridge, which the commander-in-chief granted, broadly hinting that "the present situation of affairs" required the presence of every officer and he hoped, if possible, that he return within the time mentioned. "I wish you a pleasant journey."

On the same day Stirling was given leave, a more uneasy problem was broached by Major Henry Lee, whose free-ranging dragoons controlled lower Orange to the very perimeters of Stony Point. According to one of the enemy garrison on the promontory, no less than thirteen American deserters had come into the British post on July 6 with prevailing rumors of an American attack, which Lee deemed sufficient reason to suggest to Washington two days later that deserters should be put to death instantly on capture and their heads should be cut off and sent to their units as an example - a dire proposal that was to reach its sad culmination within days in Smith's Clove.

MAJOR HENRY LEE (1756-1818), Washington's eyes and ears in lower Orange (now Rockland) County in the summer of 1779. In 1807 his wife Ann gave birth to a son, Robert Edward Lee, who will gain fame in the Civil War as commander of the fabled Army of Northern Virginia to the time of its demise at Appomattox Court House. Portrait by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Independence Hall Collection, Philadelphia.

MAJOR HENRY LEE (1756-1818), Washington's eyes and ears in lower Orange (now Rockland) County in the summer of 1779. In 1807 his wife Ann gave birth to a son, Robert Edward Lee, who will gain fame in the Civil War as commander of the fabled Army of Northern Virginia to the time of its demise at Appomattox Court House. Portrait by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Independence Hall Collection, Philadelphia.

Lee's onerous solution was put to a severe test that very night before he even had opportunity to receive a return opinion from headquarters, when one of his patrols apprehended three more deserters on their way to the enemy - these, from the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment - and an argument arose as to what was to be done with them. Some wanted to kill all three on the spot immediately without trial or orders, while others advised delay, and it was finally agreed to eliminate only one - an unfortunate corporal chosen by lot who was summarily hanged and had his head hacked off.

In a letter to the commander-in-chief from Haverstraw on July 9, Lee apprised him of the execution, and the two remaining deserters were taken under guard with the severed head to the Clove where the Pennsylvanians lay and were forced to carry the gruesome object on a pole through the camp amid the stunned soldiery and see it affixed to the gallows as a warning to all.

Washington at New Windsor was appalled at what happened. On receiving Lee's first letter, suggesting death and decapitation, he replied on the ninth that instant execution for desertion would probably be a deterrent, though it was something to be handled cautiously and only if attending circumstances were clear and unequivocal - but as for cutting off heads as a matter of policy, he was adamant in ordering that it "better be omitted." "Examples, however rare," he said, "ought not to be attended with an appearance of inhumanity; otherwise, they give disgust and may excite resentment rather than terror."

He learned of the extreme brutality of what finally happened when he received Lee's second letter on July 10, but, returning word to his energetic twenty-three-year-old subordinate, could do little more than express his abhorrence and firmly forbid further irregularities of this nature. "I wish mine of the same date," he confided, "had gotten to hand before the transaction you mention had taken place. I fear it will have a bad effect both in the army and in the country. I would by no means have you carry into execution your plan of diversifying the punishment, or in any way to exceed the spirit of my instruction yesterday. And even the measure I have authorized ought to be practiced with caution." The execution evidently had taken place within close proximity to Stony Point, for in a postscript Washington added: "You will send and have the body buried lest it fall into the enemy's hands."

Brigadier-General William Irvine, who commanded one of the Pennsylvania brigades in St. Clair's division, saw the blood-caked head on the gallows and wrote to Wayne at Fort Montgomery on the tenth that the two surviving "villains" had been brought to trial that day and presumably would share the same fate. "I hope in future Death will be the punishment for all such. I plainly see less will not do." They were hanged the next day; but they, unlike the corporal, kept their heads.

On July 16 the uneasy stalemate on the Hudson came to an abrupt end when, at 9:30 in the morning, Washington received a two-sentence report from Anthony Wayne that Stony Point and the entire garrison had been surprised and taken by the light infantry. It was the military highlight of the year, brilliantly conceived and executed and superb for morale, but its strategic effect was negligible. After the removal of prisoners, cannon and stores, it was abandoned two days later and on the third was reoccupied by Sir Henry Clinton and troops from downstream - who even then was not without hopes that "Mr. Washington" was finally being drawn into the general battle he had sought since spring. The King's Ferry posts were both quietly retained by the British for another three months until their final evacuation in October.

Interestingly, Smith's Clove played a small - if insignificant - role in the aftermath of Stony Point as part of the route traversed by the 472 British captives on their way to confinement in Pennsylvania. Setting forth from Stony Point under military guard on the day of its capture, they camped overnight at Kakiat and on July 17 continued by way of the western road to Suffern's, where they turned into the Clove and marched across Sidman's bridge to Slot's and turned into Eagle Valley Road and on to Sterling and over the mountain to Chester and Goshen and onto the great Sussex road along which Burgoyne's captive army had been taken to the Delaware eight months earlier.

For the first and only time during the war, British redcoats in force made an appearance in Smith's Clove - their line of march known from the pen of a loyalist who heard of it from a captive officer taken at Stony Point and given his parole. The captured ordinance was likewise removed and letters dispatched by Virginia officers from June's tavern and Smith's on the nineteenth and twentieth make reference to its transport and safe arrival at Suffern's.

Part I

Introduction

Clove and Precinct

The Clove Road

The Clove Taverns

Clove Taverns II

Part II

Prelude to War

The Continentals Arrive

Blocking the Clove

In the Midst of Tories

Offensive from the Highlands

The Militia Take Over

The Post at Ramapo

The Reluctant Militia

Holding the Line

An Embarrassing Situation

To Galloway's and Back

The Scotsman's Regiment

September Raid

Prelude for Disaster

Clinton Takes the Highlands

Sidman's Bridge: The Last Holdout

Part III

Introduction

Summer, 1778

A Cogent Appraisal

Villains and Robbers

Part IV

Introduction

Aaron Burr's Ride

March to the Clove

The Barren Clove

Bracing for Attack

Among the Rocks and Rattlesnakes

The Present Interesting Occasion

A Waiting Game

Redeployment

The Continental Road

The Taphouse Keeper's Daughter

The Indian Fighters Appear

March to Morristown

Part V

Introduction

A Fruitless Excursion

Summer at the Clove

A Frenchman's Journey

Pompton Mutiny: Blood in the Snow

Blockhouse in the Clove

The Allies at New Antrim

The Intercepted Messenger

A Questionable Story

What Really Happened

Perils of A Post Rider

New Yorkers at the Clove

Congress' Own Regiment

The Last Garrison

A Man of Passion

Homeless Canadians

The Last March

Part VI

Introduction

The Post at Sidman's Bridge

Marking the Site