Corridor Through the Mountains

Smith's Clove: Wartime Line of Communication and Passageway for the Continental Army, 1776-1783

Richard J. Koke

[Editor's Note: Richard J. Koke authored a series of five articles that appeared in Volumes 19 -23 of the OCHS Journal between 1990 and 1994. These articles will be presented in multiple sections over the next few years.]

Part V:

Finally, A Dreary Blockhouse

Chapter 5:

Pompton Mutiny: Blood in the Snow

For the commander-in-chief, seventeen eighty-one opened in the worst way possible. On New Year's Day, the Pennsylvania line at Morristown mutinied, and twenty days later - one month after Chastellux traveled the Clove - the New Jersey line rose in revolt at Pompton. The Pennsylvania outbreak was settled by negotiation; the Jersey insurrection ended deadly. Pompton mutiny started on a Saturday; seven days later it ended on a Saturday, and once again Smith's Clove was to be a lifeline for military movement.

About ten o'clock on Sunday night, January 21, word of the trouble at Pompton reached Washington at his Ellison house headquarters at New Windsor. Already experiencing the trauma of the Pennsylvania revolt, he was in no mood to temporise further. He was finished with provocation; this matter would be handled in his own way. There would be no negotiation, no haggling, no compromise. He sent word immediately to the New Jersey officers to collect whatever loyal troops they could to restore order, and the "more decisively you are able to act the better." He dispatched word to Heath at West Point that he was determined "at all hazards" to put an end to unruly proceedings that could spread and infest the entire army and bring about its utter ruin and dissolution, and ordered him to prepare a detachment of 500 or 600 men for a march into New Jersey.

On Monday, he went to West Point to expedite matters and assigned command of the detachment to Major-General Robert Howe with orders to march on the following day and rendezvous either at Ringwood or Pompton and compel the mutineers to unconditional submission. No terms were to be granted while they were in a state of resistance, and if he was successful in forcing surrender "you will instantly execute a few of the most active and most incendiary leaders."

On Tuesday, the Massachusetts troops assigned to accompany Howe left their mountain huts behind West Point and started towards the Clove by the inland road (now Route 293) that went by way of Long Pond and the Forest of Dean. Pompton lay twenty-three miles from the Point in a direct line, but the difficult terrain made it seem longer, and to make everything worse a heavy snowfall had started on Monday that continued through the night and by Tuesday the region was isolated; horses were difficult to procure and the snow delayed all transport.

Dr. James Thacher, surgeon, who had been in the Clove with the Virginians in 1779 but was now with the New Englanders, wrote that "a body of snow, about two feet deep, without any track, rendered the march extremely difficult. Having no horse, I experienced inexpressible fatigue and was obliged several times to sit down on the snow." On reaching the Forest, at what is now Stillwell Lake on the West Point military reservation, they crowded for the night into whatever buildings were available at the ironworks.

Thacher's assertion that the next day's march was by way of Earl's tavern at Highland Mills (which he misidentified as "Carle's"), indicates the road taken from the Forest was that which went by way of the lonely Bull house and joined the Clove Road in front of the tavern on the line of Park Avenue. Howe rested the troops for two hours and then pushed on through Central Valley, and after a march of thirteen grueling miles halted for the second night and put up in houses and barns, probably somewhere in the vicinity of Galloway's tavern at Southfields.

On Thursday, five days after the mutiny had broken out, he sent a report to Washington from the Clove that the men were marching without hesitation, and continued for nine more miles, according to Thacher, and after three days in the snow finally arrived at Ringwood, where a detachment of one hundred Connecticut troops was stationed under Major Benjamin Throop to guard the magazine.

The hospitality of the widow Erskine's house was quickly made available and Howe and his officers were welcomed after the dogged march. Their hostess, whom Thacher called "the amiable widow of the late respectable geographer of our army," entertained them "with an elegant dinner and excellent wine," and she impressed him as "a sensible and accomplished woman" who lived in a style of affluence and fashion, every thing indicates wealth, taste and splendor; and she takes pleasure in entertaining the friends of her late husband with generous hospitality."

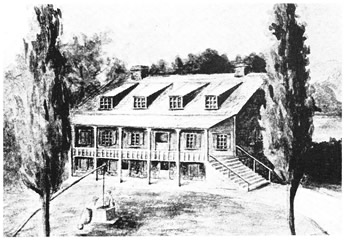

ROBERT ERSKINE HOUSE, Ringwood State Park, New Jersey When Robert Erskine arrived at Ringwood in 1771 to manage the ironworks, he moved into a "large dwelling house" on the grounds formerly occupied by the ironmaster Peter Hasenclaver and previous owners, and here spent the remaining nine years of his useful life. In 1771 he wrote that "the mansion house has been patched together at different times which makes it a very acquard [awkward) piece of architecture"; but it must have been commodious and comfortable despite his implication that it was of architectural ungainliness. Chastellux called it in 1780 "a very handsome house". In 1804, when again offered for sale, it was advertised as "an elegant Mansion House, 92 feet front, and about 30 feet deep", on which a large sum of money had been expended to put it "in perfect repair". The house either burned or was razed around 1807 when it came into the possession of the Ryersons. When Abram S. Hewitt acquired the property and moved to Ringwood in 1857 he commissioned an artist to paint a picture of the house from descriptions given by elderly people who remembered the building, a small watercolor now in the collection of the Manor House at Ringwood State Park and here reproduced. As given, it shows decided Hudson Valley architectural features similar to the Van Cortlandt Manor House at Croton and the Colonel Thomas Ellison House formerly on the river bluff at New Windsor. Edward Ringwood Hewitt, Abram's son, who knew the Ringwood country, stated in old age in 1946 that the house stood in front of the present Manor House in Ringwood State Park, and in very dry seasons the line of the rear wall of Erskine's house beneath ground level was discernible through discoloration of the earth and grass.

ROBERT ERSKINE HOUSE, Ringwood State Park, New Jersey When Robert Erskine arrived at Ringwood in 1771 to manage the ironworks, he moved into a "large dwelling house" on the grounds formerly occupied by the ironmaster Peter Hasenclaver and previous owners, and here spent the remaining nine years of his useful life. In 1771 he wrote that "the mansion house has been patched together at different times which makes it a very acquard [awkward) piece of architecture"; but it must have been commodious and comfortable despite his implication that it was of architectural ungainliness. Chastellux called it in 1780 "a very handsome house". In 1804, when again offered for sale, it was advertised as "an elegant Mansion House, 92 feet front, and about 30 feet deep", on which a large sum of money had been expended to put it "in perfect repair". The house either burned or was razed around 1807 when it came into the possession of the Ryersons. When Abram S. Hewitt acquired the property and moved to Ringwood in 1857 he commissioned an artist to paint a picture of the house from descriptions given by elderly people who remembered the building, a small watercolor now in the collection of the Manor House at Ringwood State Park and here reproduced. As given, it shows decided Hudson Valley architectural features similar to the Van Cortlandt Manor House at Croton and the Colonel Thomas Ellison House formerly on the river bluff at New Windsor. Edward Ringwood Hewitt, Abram's son, who knew the Ringwood country, stated in old age in 1946 that the house stood in front of the present Manor House in Ringwood State Park, and in very dry seasons the line of the rear wall of Erskine's house beneath ground level was discernible through discoloration of the earth and grass.

Apprised of the situation at Pompton from what he could learn at Ringwood, Howe wrote again to the commander-in-chief and informed him that the mutineers had gone off to Chatham but were returning to Pompton. He held the letter overnight, and at 7:00 on Friday morning added a postscript that two hundred of the insurgents were back in their huts, expecting to negotiate, and unless he was forbidden from taking measures to act in conformity with orders he had received when they parted at West Point - unconditional submission - he was confident he could bring the undertakng to a conclusion "in a manner more consistent with your Excellency's wishes" than mediation and without much trouble or bloodshed.

Howe remained at Ringwood all day while other contingents from east of the Hudson were approaching Pompton by way of King's Ferry, and during the day he was joined by a detachment of Continental artillery with three field pieces that had been dispatched the day before from the artillery park at Murderers Creek.

By Thursday, January 25, Washington at New Windsor knew no more of what was going on at Pompton on the other side of the mountains than what he had learned on Sunday night. Added to his uncertainty, was a fear that the British might attempt a sortie from New York to take advantage of the unrest to foment further trouble. During the day, while Howe's troops were trudging towards Ringwood and the field pieces were on their way down the Clove, the commander-in-chief determined to ride forward himself to ascertain the situation, and he wrote to Howe of his intent to set out "towards you" on the next day and requested him to forward any information that he could receive "somewhere on the road." And in preparation, he sent an order to Colonel Timothy Pickering, his quartermaster-general, to send a sleigh and a pair of horses and a driver to headquarters at 8:00 the next morning to take him to Smith's tavern, where he would be provided with a relief and the sleigh would then return - and he added a word of caution: "I would have no notice taken of these being wanted for my use."

Early on Friday, accompanied by the Marquis de Lafayette and his newly-married aide, Hamilton, the commander-in-chief left Ellison's and headed down the Clove in deep snow to Captain Smith's hostelry, where Lieutenant Philip Strubling of the Maréchausée Corps was waiting with a cavalry escort. The silent cortege, heavily clothed against the chill, continued past lonely houses amid the white stillness and late in the day, close to midnight, Washington and the hardened dragoons of the Maréchausée reached the Erskine house at Ringwood.

Within a short time, Hamilton was writing to a friend that they were there "on the business of the Jersey revolt" and "tomorrow it will be brought to a decision." Lafayette, who had gone along in case a ranking officer would be necessary to oppose the British in case of a move from New York, wrote to the French Minister that Washington was determined to pursue rigorous measures and four hundred men were ready to move against the mutineers, but under the circumstances, with nothing to do, he intended returning to New Windsor in the morning.

An attempted negotiation with the mutineers by a New Jersey commission had broken down, and the men remained unruly and riotous. Free of civil interference, Washington went ahead with his original plan - no negotiation, no terms, no compromise. The final order was given and at 1:00 on Saturday morning Howe and his New England Continentals, outnumbering the mutineers two to one, set forth on the eight-mile night march to Pompton. Washington remained at Mrs. Erskine's.

At dawn, Howe surrounded and trained his 3-pounders on the huts, and the mutineers were paraded without arms. What happened next, happened quickly. Three of the ringleaders, standing in the snow, were given a summary court martial and were condemned and ordered executed. Two, placed on their knees, were shot (twelve of their weeping comrades assigned as executioners); the third was pardoned. The mutiny was over. On the next day a visitor found everything "very peaceable" in the camp, but in the bitter aftermath the Jerseymen did not forgive the hated New Englanders for their part in the bloody suppression.

Washington stayed at Ringwood all day on Saturday while order was being restored. On Sunday he returned to New Windsor, but before leaving he instructed the commanding officer of the Jersey line that if the Jersey post in the Clove and another at Dobbs Ferry were in any way "deranged" as a result of "the late disturbances" they were to be reestablished in conformity with the orders issued in November.

Howe and his troops remained at Pompton for four days after the executions to guard against any further disturbance, and on January 31 retraced their way through the Clove and Forest to West Point. For one soldier, however, the return turned out to be more than he anticipated and took him full cycle back to where he had started. Lieutenant William Pennington, who had come with the artillery from New Windsor, went to Pompton from Ringwood on Sunday and then to the nearby Ponds Church at Oakland for an overnight visit with some cousins; but instead of rejoining his unit at Ringwood by the way he came, he chose to leave on Monday by the main road (now Route 202) that led east along the Ramapo escarpment to Suffern's, where he turned into the Clove with intent to overtake his artillery in the corridor on its return. However, on reaching Warwick Brook, where the Clove highway joined the new road seven miles above Mrs. Sidman's, he was surprised to learn that the artillery was still at Ringwood and he had to make his way back to the ironworks, after going a good fourteen miles out of his way. He and his detachment left on Tuesday, and after another night in the Clove arrived back at the artillery park on Wednesday. He confessed his weariness when he wrote in his diary of his return, "having had 7 Days continued fatigue at this Season, and there being a large body of Snow on the ground."

Thereafter, in coming months, the garrisoning of the lower Clove continued in a state of flux. On February 7, in a complete realignment of positions, Washington wrote again to the commanding officer of the New Jersey troops and ordered the withdrawal of the Dobbs Ferry detachment, and that a captain's company of about forty men should be posted "at the entrance of Smiths Clove" and another either at Pompton or Ringwood to protect the stores and country, and all remaining troops were to be marched to Morristown and quartered in the empty Pennsylvania huts.

A few weeks later, as part of a broad plan to arrange militia support for West Point if threatened by the enemy, he ordered Colonel Ann Hawkes Hay of the Haverstraw militia to send detachments "to possess the entrance of the Clove at sufferans" and other pathways leading into the mountains, but no evidence exists that such a course became necessary. The continued presence of the Jerseymen at the corridor was still apparent in May when Washington placed the Jersey brigade under marching orders, but "the parties at the Clove are not to be immediately called in." However, the officers, if called upon, were to be ready to move.

Part I

Introduction

Clove and Precinct

The Clove Road

The Clove Taverns

Clove Taverns II

Part II

Prelude to War

The Continentals Arrive

Blocking the Clove

In the Midst of Tories

Offensive from the Highlands

The Militia Take Over

The Post at Ramapo

The Reluctant Militia

Holding the Line

An Embarrassing Situation

To Galloway's and Back

The Scotsman's Regiment

September Raid

Prelude for Disaster

Clinton Takes the Highlands

Sidman's Bridge: The Last Holdout

Part III

Introduction

Summer, 1778

A Cogent Appraisal

Villains and Robbers

Part IV

Introduction

Aaron Burr's Ride

March to the Clove

The Barren Clove

Bracing for Attack

Among the Rocks and Rattlesnakes

The Present Interesting Occasion

A Waiting Game

Redeployment

The Continental Road

The Taphouse Keeper's Daughter

The Indian Fighters Appear

March to Morristown

Part V

Introduction

A Fruitless Excursion

Summer at the Clove

A Frenchman's Journey

Pompton Mutiny: Blood in the Snow

Blockhouse in the Clove

The Allies at New Antrim

The Intercepted Messenger

A Questionable Story

What Really Happened

Perils of A Post Rider

New Yorkers at the Clove

Congress' Own Regiment

The Last Garrison

A Man of Passion

Homeless Canadians

The Last March

Part VI

Introduction

The Post at Sidman's Bridge

Marking the Site