Corridor Through the Mountains

Smith's Clove: Wartime Line of Communication and Passageway for the Continental Army, 1776-1783

Richard J. Koke

[Editor's Note: Richard J. Koke authored a series of five articles that appeared in Volumes 19 -23 of the OCHS Journal between 1990 and 1994. These articles will be presented in multiple sections over the next few years.]

Part IV:

1779: A Crucial Year

Chapter 5:

Bracing for Attack

Smith's Clove was a superb base from where Washington could move to West Point or, if need be, back into New Jersey. His immediate objective was to form a front to the river, from where an attack could come, and to station his divisions at the junctions where the crossroads from the east joined the Clove Road at June's tavern, Earl's tavern and the Van Ambrose house, where the approaches could be contested if an attack came or the crossroads used for an offensive advance.

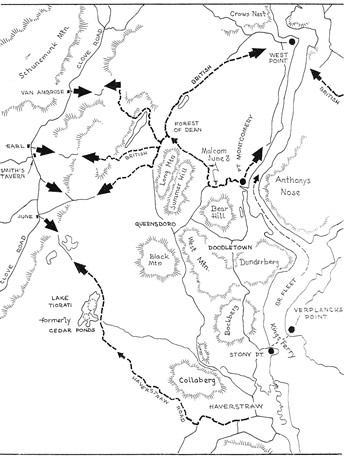

DANGER FROM THE HUDSON: BATTLE TACTICS IN THE HIGHLANDS June 1779. Map of the Highland terrain between the Hudson River and Smith's Clove, showing conjectured routes of British attack against West Point and into Smith's Clove anticipated by the American Highland command immediately after the British capture of King's Ferry on May 31-June 1, 1779. The American defenders were convinced that a three-pronged offensive against West Point was imminent, not only by way of the river with a fleet of about forty sail but through the mountains on both sides of the Hudson. As envi. sioned by the Americans, one force, operating on the east shore, would advance from Peekskill through the Continental Village and Gorge of the Mountains to the river shore opposite West Point to form a linkage with the fleet. Another force, operating west of the Hudson, would debark from the ships in Popolopen Kill below the ruins of Fort Montgomery and would push inland by Mine Road to the Forest of Dean, and from there would advance north along what is now Route 293 to envelop West Point from the rear while the fleet and support units pressed in from the river. It was also considered probable that enemy detachments, guided by sympathizers among the mountain inhabitants, would descend into the Clove from the Forest by any of the several pathways indicated to cut the main line of communication through the western Highlands. Another threat to the corridor from the river, where the British were in strength, was by way of the ten-mile-long Haverstraw road at bottom left, now vanished, which crossed the mountains between lower Orange (now Rockland) County and June's tavern and served as a crucial artery throughout the summer of seventy-nine. The uneasy situation was stabilized somewhat by the end of the first week. The endangered Fort Montgomery crossroad between the river and Forest was quickly blocked by Colonel Malcom and his New York militiamen from West Point on June 3. Washington, hurrying with his main force from New Jersey, entered the Clove on June 6 and formed a front to the river along the clove Road between June's tavern and the Widow Van Ambrose at Woodbury, positioning his three divisions, as indicated at the left, athwart the heads of the lateral roads from the Forest and Haverstraw from where attack could be expected. Sir Henry Clinton's offensive never materialized. He had an eye on West Point, but considered an immediate thrust hazardous following the seizure of King's Ferry; awaiting, instead, the arrival of reinforcements from Europe before undertaking any serious drive into the mountains. The eagerly awaited reinforcements, however, never arrived until August when the season for campaigning was late and the military picture was completely changed. The isolated British garrison was withdrawn from the remote ferry outpost at the gate of the Highlands which for five months - save for a few days in July, when Anthony Wayne gained glory - had served as a dangerous threat to West Point and hindered the transport of American troops and supplies and prevented communication across the Hudson between New England and the other colonies.

DANGER FROM THE HUDSON: BATTLE TACTICS IN THE HIGHLANDS June 1779. Map of the Highland terrain between the Hudson River and Smith's Clove, showing conjectured routes of British attack against West Point and into Smith's Clove anticipated by the American Highland command immediately after the British capture of King's Ferry on May 31-June 1, 1779. The American defenders were convinced that a three-pronged offensive against West Point was imminent, not only by way of the river with a fleet of about forty sail but through the mountains on both sides of the Hudson. As envi. sioned by the Americans, one force, operating on the east shore, would advance from Peekskill through the Continental Village and Gorge of the Mountains to the river shore opposite West Point to form a linkage with the fleet. Another force, operating west of the Hudson, would debark from the ships in Popolopen Kill below the ruins of Fort Montgomery and would push inland by Mine Road to the Forest of Dean, and from there would advance north along what is now Route 293 to envelop West Point from the rear while the fleet and support units pressed in from the river. It was also considered probable that enemy detachments, guided by sympathizers among the mountain inhabitants, would descend into the Clove from the Forest by any of the several pathways indicated to cut the main line of communication through the western Highlands. Another threat to the corridor from the river, where the British were in strength, was by way of the ten-mile-long Haverstraw road at bottom left, now vanished, which crossed the mountains between lower Orange (now Rockland) County and June's tavern and served as a crucial artery throughout the summer of seventy-nine. The uneasy situation was stabilized somewhat by the end of the first week. The endangered Fort Montgomery crossroad between the river and Forest was quickly blocked by Colonel Malcom and his New York militiamen from West Point on June 3. Washington, hurrying with his main force from New Jersey, entered the Clove on June 6 and formed a front to the river along the clove Road between June's tavern and the Widow Van Ambrose at Woodbury, positioning his three divisions, as indicated at the left, athwart the heads of the lateral roads from the Forest and Haverstraw from where attack could be expected. Sir Henry Clinton's offensive never materialized. He had an eye on West Point, but considered an immediate thrust hazardous following the seizure of King's Ferry; awaiting, instead, the arrival of reinforcements from Europe before undertaking any serious drive into the mountains. The eagerly awaited reinforcements, however, never arrived until August when the season for campaigning was late and the military picture was completely changed. The isolated British garrison was withdrawn from the remote ferry outpost at the gate of the Highlands which for five months - save for a few days in July, when Anthony Wayne gained glory - had served as a dangerous threat to West Point and hindered the transport of American troops and supplies and prevented communication across the Hudson between New England and the other colonies.

On Sunday the sixth, three days after the commander-in-chief had departed Middlebrook, the main army entered the Clove. St. Clair and the Pennsylvania division came from the Ringwood hills and led the way along Eagle Valley Road into what is now Sloatsburg and after a halt at Slot's turned left and pushed five miles up the Clove Road to Galloway's tavern at Southfields, where Washington had stopped two years earlier. During the course of Sunday and Monday, the troops were deployed through the entire length of the corridor.

Major Lee and his cavalry rode to the mouth of the Clove and was joined at Suffern's by two light infantry companies detached from de Kalb's division, and then continued around the Point of the Mountains into lower Orange and Kakiat to "plague the enemy" (the words are Washington's) and afford protection against the depredations of raiding parties from Stony Point which thus far Colonel Hay could do little to prevent.

Washington rode in and took quarters at Slot's, from where General Orders on Sunday directed the Pennsylvania division to encamp at June's or in the vicinity, and that three or four hundred light infantrymen were to be sent "into the passage of the mountain" to reinforce Colonel Malcom on the Fort Montgomery crossroad and remain until further orders. The Virginia division was to proceed to Smith's tavern, and the Maryland division was to move by way of Slot's and Galloway's and join the other troops. All divisions were to march "at the rising of the moon."

The movement into the Clove was not without problems. All day on Sunday, Major-General Greene watched the army toil through Ringwood, and in the evening he sent a complaining letter to Washington that some solution would have to be found to curtail the amount of baggage that was being hauled, and it would be necessary to separate superfluous baggage from what was necessary. He saw teams fail and overloaded wagons break down that were impossible to replace. Regiments had more wagons than ever allowed before - the Pennsylvania line alone having between sixty and seventy - and yet there was constant call on his department for more. And, as a crowning touch, the wagons were loaded with women and lazy soldiers. "There must be some new order on this subject," he urged, "to prevent their riding."

That an enemy thrust across the mountains from the river was still anticipated was evident when Washington posted a letter from "Head Quarters" on Sunday to St. Clair at Galloway's and called his attention to the ten-mile-long mountain path that led from June's tavern to Haverstraw over which the British could advance and intercept their line of march in the Clove, and he ordered him to send a good subaltern with a reconnaissance party forward as close to the enemy as possible and return word of any British movement, and suggested it would be useful if some of the "well affected" inhabitants acquainted with the country could accompany the detachment as guides. "The officers that commands your party," he said "should be cautioned against mistakes."

Washington's perception was acute, for on that very Sunday, Captain Patrick Ferguson (who will die at King's Mountain), led a British "alert" from Stony Point into the Haverstraw countryside and was on his return with cattle when he nearly encountered "the advanc'd Guard of Genl. Sinclair's Corps" as he was passing the country homes of the New York lawyers William and Thomas Smith on the main highway (now Route 9W) at present-day West Haverstraw.

On Monday, after paying "for Lodging and Milk" at Slot's, Washington rode fourteen miles farther up the road through what is now Tuxedo, Southfields, Harriman and Central Valley to Captain Smith's tavern on the Clove Road opposite the highway leading west to Chester, where Continental headquarters was established and remained for fourteen days until June 21. The commander-in-chief's Life Guard, marching twenty-five miles from Ringwood through the confusion of an army operation, also joined him on the seventh and pitched tents near the tavern.

The final disposition for the locations of the encampments appeared in General Orders issued from Smith's tavern on Monday after Washington's arrival. Stirling and the Virginia division - which was to remain in the Clove longer than the other two - was to take post "near the road leading from June's to the Forest of Deane" in the area of Turner Road and Woodbury Common in lower Central Valley. De Kalb and the Maryland division was to take position two-and-a-half miles farther north "near the road leading from Earl's" to the Forest, now Park Avenue at Highland Mills; and St. Clair and the Pennsylvania division was to take post another two miles farther on near the road leading to the Forest from the home of the Widow Van Ambrose on what is now Route 32 at Trout Brook Road in Woodbury Valley. Shortly thereafter, from June 14 to July 17, the Pennsylvanians camped on the farm of John W. Smith in the broad valley bottom in the Mountainville countryside. Each division was to furnish pickets and patrols for security "on the avenues leading from the enemy", and the officers were ordered to acquaint themselves as best as possible with the roads and by-paths leading towards the enemy and the Forest and West Point.

Reports drifting into the British lines at New York were routinely published by James Rivington in his Royal Gazette, in which he announced in early June that by the latest accounts received, "Mr. Washington" was "serenely embowered at Smith's Clove", most of his artillery was at Ringwood and about three hundred of his dragoons - Lee's corps - were at Kakiat.

And here, Washington waited.

Part I

Introduction

Clove and Precinct

The Clove Road

The Clove Taverns

Clove Taverns II

Part II

Prelude to War

The Continentals Arrive

Blocking the Clove

In the Midst of Tories

Offensive from the Highlands

The Militia Take Over

The Post at Ramapo

The Reluctant Militia

Holding the Line

An Embarrassing Situation

To Galloway's and Back

The Scotsman's Regiment

September Raid

Prelude for Disaster

Clinton Takes the Highlands

Sidman's Bridge: The Last Holdout

Part III

Introduction

Summer, 1778

A Cogent Appraisal

Villains and Robbers

Part IV

Introduction

Aaron Burr's Ride

March to the Clove

The Barren Clove

Bracing for Attack

Among the Rocks and Rattlesnakes

The Present Interesting Occasion

A Waiting Game

Redeployment

The Continental Road

The Taphouse Keeper's Daughter

The Indian Fighters Appear

March to Morristown

Part V

Introduction

A Fruitless Excursion

Summer at the Clove

A Frenchman's Journey

Pompton Mutiny: Blood in the Snow

Blockhouse in the Clove

The Allies at New Antrim

The Intercepted Messenger

A Questionable Story

What Really Happened

Perils of A Post Rider

New Yorkers at the Clove

Congress' Own Regiment

The Last Garrison

A Man of Passion

Homeless Canadians

The Last March

Part VI

Introduction

The Post at Sidman's Bridge

Marking the Site