The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781

By Michael S. McGurty

Part II - "answered a very good purpose"

[Editor's Note: This article appeared in the 2009 Issue of the Journal of the Orange County Historical Society. It is being republished on the website as part of the ongoing activities surrounding the 250th Anniversary of the Revolutionary War. The footnoted version is contained in the 2009 Journal which is available for purchase. JAC]

====================

Continued from Part I...

Though protected from small pox, the soldiers were still susceptible to a variety of contagious diseases and those brought about by poor diet and primitive living conditions. They were generally dirty, with winter hygiene limited to shaving every few days and possibly the daily washing of the face and hands. Such conditions bred diseases like the bacteriological skin infection of impetigo, commonly known as the “itch”. Soldiers had to rub lard mixed with sulphur on the afflicted areas.

Hut building was an activity fraught with danger. A drummer “jammed his little finger + the one next to it, with a Stone the former of which was broken in the bone at the hand.” A week later, Dr. Adams had to amputate the little finger. Another unfortunate soldier “cut his foot with an axe.”

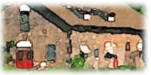

A portion of a Simeon Dewitt Map – “The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity

for 1783.” The hospital building shown served as artillery huts in 1781. General Knox made his headquarters,

south of the camp, at the house marked “Jn Ellis” (John Ellison). New Windsor and the Hudson River are to the right of this map, Snake Hill is just to the north. New-York Historical Society Digital Collection. Click on image to enlarge.

A portion of a Simeon Dewitt Map – “The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity

for 1783.” The hospital building shown served as artillery huts in 1781. General Knox made his headquarters,

south of the camp, at the house marked “Jn Ellis” (John Ellison). New Windsor and the Hudson River are to the right of this map, Snake Hill is just to the north. New-York Historical Society Digital Collection. Click on image to enlarge.

Discipline in camp was harsh. The high appearance standards and conduct demanded by the military clashed with the devil may care attitude of most Americans. Much effort was put into cajoling and threatening the soldiers to aspire to the ideals of dress and decorum that the officers had in mind. According to Baron von Steuben in his Regulations For The Order And Discipline Of The Troops Of The United States:

The oftener the soldiers are under the inspection of their officers the better;… for which reason every morning at troop beating they must inspect into the dress of their men; see that their clothes are whole and put on properly; their hands and faces washed clean; their hair combed; their accoutrements properly fixed, and every article about them in the greatest order.

In February, the conduct of the muster parade and inspections was specifically enumerated in the 2nd Continental Artillery orderly book. Usually conducted monthly, the muster parade was “a review of troops under arms to see if they” were “in good order [and] to take an account of their numbers.”

During good weather, the arms were “lodged on the Racks in front of the Barracks” so they could be inspected at any time. This measure also precluded the soldiers from taking their arms to fire at game.

The officers made every effort to acquaint the men with their duties and the regulations governing their conduct. Well aware however, “of the evil that men do” anyway, the first structure built in camp was the guard house.

While additional training and increased supervision were used to correct deficiencies in military duty performance, soldiers who violated the Articles of War were dealt with severely. The harshness of camp discipline might be partly responsible for the 30 desertions, over the course of the winter.

Enacted by the Continental Congress to regulate conduct within the Army, the Articles of War contained not only statutes derived from English common law, but those regarding the peculiar military offenses of insubordination, mutiny and desertion. Soldiers convicted by a court martial usually received some form of corporal punishment, the ultimate sanction being death.

Cornelius Hague, from the 2nd Artillery, was sentenced for being absent 24 hours “to wear a log [block] of thirty pounds weight [for] three days.” The unfortunate soldiers were usually forced to work on all fatigues while wearing the block. His sentence however, was remitted the next day, because he was a new recruit.

John Welch, also from the 2nd, for the same offense was sentenced to “stand in the Cage twenty four hours and be fed only with bread and water.” Sergeant George Garland, another soldier from the 2nd, for “riotous behaviour at the house of Mr. Hortons, Disobedience of Orders, collaring and attempting to strike Lieut Giles” received one hundred lashes with a whip and was reduced to a matross. James Cunningham received “100 lashes on his back with switches” for absenting himself and fraudulently borrowing money from some inhabitants. A young fifer received the Biblical allotment of 39 lashes, for stealing a pair of silver shoe buckles.

Despite the probable feelings of enlisted soldiers, to the contrary, the officers did not delight in meting out these punishments.

"The Commandant [of the 2nd Artillery Lieutenant Colonel Stevens] sincerely laments the great necessity there has been for so many Court Martials of late, and it is with pain he finds that the many Punnishments that have been inflicted have not had the desired Effect – He wishes to assure the Men that it is not his Inclination to see them punished on the contrary, it wou’d afford him real pleasure, if there was not occasion for another Court Martial in the Regt – but if Soldiers are so lost to every sense of Rectitude so regardless of their own honor and that of the Corps, as to forget the sacred duties they owe to their Country; and act in direct violation of every virtuous Principle, they must expect the Rewards due to their crimes.

In many cases where he was lenient, the soldiers went on to carry out even more heinous offenses. He requested that company commanders read the Articles of War and the responsibilities of the non-commissioned officers out of the Steuben Manual to their soldiers monthly.88 Nothing seemed to deter some of the soldiers from repeatedly committing offenses.

Matross Henry Harris, from the 2nd Artillery, appeared before a court martial several times, over the course of the winter, for crimes of theft, drunkenness and insubordination. Short of execution, there was nothing more the officers could do, because their sentence options, in the most serious cases, were limited by the Articles of War, to upwards of 100 lashes or death. The military courts had no qualms about condemning offenders to death, but they readily passed this judgment, because most executions were never carried out. Having been set aside in so many instances, the death sentence had all but lost its deterrent effect.

Ironically, soldiers who committed the most serious offenses often escaped punishment, while those who were guilty of lesser crimes were usually punished with vigor. Washington believed that the “great part of the vices [in] discipline” was caused by this inequity. Though, he warned Congress that without “a proper gradation of punishments in our military code”, officers would resort to potentially excessive arbitrary sentences, his appeal for authorization to increase punishments to upwards of 500 lashes, service on a man of war or hard labor on some public project was defeated.

Overindulgence was the cause behind many of the crimes and derelictions of duty. Forbidden to leave the camp without permission, the soldiers looked to alcohol to ease their boredom. General Knox observed that “a number of tippling houses were opened by the Soldiers in the Park”. Provoking “much Diforder and Irregularity” he banned his soldiers from “selling liquor of any kind”.

In December, Stevens forbid any huts to be built out of the main line, because of the tendency for excesses to be committed in them. He must have relented to their construction however, because he had to forbid the sale of cyder and other spiritous liquor in the huts detached from the main line under “pain of having [the] Hutts pulled down.”

Some of the officers were hardly the paragons of virtue either, but they were generally more discreet. On December 3, almost every officer, in the park, called at the tent of Captain George Fleming [of the 2nd Artillery] to partake in some brandy. “Some that went there sober did not come [out] sober.”

Drinking, “may do for once in away, but not to make a practice of.” Dr. Adams broke his resolution to limit his drinking again and again. The officers sought consolation in the bottle just like the enlisted soldiers, because they too were quite bored.

One night, Dr. Adams was reading the Boston Chronicle for 1767. His eclectic selections also included a romantic comedy: the Beau Stratagean, Richard the III and “assorted novels.” Card games were also a favorite source of amusement. The aurora borealis made a spectacular appearance on January 21.

Women were a welcomed diversion. Officer wives made visits, Martha Washington foremost among them. Soldiers in search of female companionship organized dances with local women, but those who wanted to be assured of finding a pliant partner, had only to seek out the sporting houses that would invariably spring up in the vicinity of the camps.

There were dangers however, in the search for intimacy. Besides the ever present specter of venereal disease, there were also unwanted pregnancies and wrathful fathers and brothers to be wary of. Unmarried women were not allowed in camp, but soldiers sometimes smuggled them in anyway.

Some of the soldiers’ wives lived with the Army. These women followed the soldiers from place to place and they were given no special consideration. Exposed to the same harsh conditions as the soldiers, they were also subject to military law. Despite the difficulties, there were so many women wanting to travel with the Army that Washington ordered a board of general officers to determine “The proportion of Women which ought to be allowed to any given number of men and to whom rations shall be allowed”.

Children trailed behind many of the women. They needed to be fed as well. Dr. Adams delivered the child of a sergeant from the park, at the home of Mr. Parsons. While the companionship of a wife and possibly children provided some comfort, caring for oneself was hard enough, without the added burden of looking after a family.

Heedless of the troubles assuredly to come, Oliver Tomsen Harden of the 2nd Artillery married Prudence from the Newburgh army on May 30, 1781, at the New Windsor Presbyterian Church.

With their freedom of movement unrestricted, the officers had access to more amusements. Adams dined with Colonel Crane and other officers from the 3rd Artillery. They were serenaded by the 3rd Artillery’s celebrated band of professional civilian musicians paid for by a subscription among the officers of that regiment.

A dinner at Colonel Stevens’ hut was attended by General Washington, Major General, the Marquis de Lafayette, General Knox, Director of the Military Hospital Doctor John Cochran and by most every officer in the park. After Washington and the Marquis left they “danced there in the evening.” The choice of Mrs. Stevens as belle of the ball was not difficult as she was the only lady present.

On two occasions Adams was invited to Washington’s headquarters. He shared the general’s table with General Robert Howe, Adjutant General Colonel Alexander Scammell and Doctor Cochran the first time and with either General George or James Clinton and the Marquis de Lafayette the second.

A Mason, Adams attended the monthly lodge meeting at West Point.

On December 20, 1780, “near the artillery barracks”, the Chevalier de Chastellux, encountered George Washington and Martha in a carriage “going on a visit” to Lucy Knox at the Ellisons. Martha Washington visited George at every opportunity, mostly during his relatively inactive winter months.

In May, the Comte de Rochambeau, commander of French forces in America, invited Washington to a conference in Wethersfield, Connecticut, because they needed to quickly decide on an objective for the upcoming campaign. Knox and the commander of the American Corps of Engineers, the Chevalier Duportail, accompanied the Commander-in- Chief. Duportail was a talented military engineer, who the French Court loaned to the Continental Army.

The Comte de Rochambeau, Major General

and Commander of the French expeditionary

force by Charles Willson Peale. A hardened veteran,

with nearly forty years service, Rochambeau

had extensive experience attacking fortified cities. He

could not have liked the Allies’ chances of breaching

the New York fortifications, given their scant

forces and the enemy multitudes. While professing

only the desire to serve under General Washington,

Rochambeau would, in practice, only follow orders

if he agreed with the decisions. He would work to

change the objective to the Chesapeake. Independence

National Historic Park.

The Comte de Rochambeau, Major General

and Commander of the French expeditionary

force by Charles Willson Peale. A hardened veteran,

with nearly forty years service, Rochambeau

had extensive experience attacking fortified cities. He

could not have liked the Allies’ chances of breaching

the New York fortifications, given their scant

forces and the enemy multitudes. While professing

only the desire to serve under General Washington,

Rochambeau would, in practice, only follow orders

if he agreed with the decisions. He would work to

change the objective to the Chesapeake. Independence

National Historic Park.

While discussing other possibilities, the relief, of the south, being foremost among them, Washington was adamant about attacking New York. Washington left the meeting with the impression that Rochambeau had coalesced with this decision. He could not have been more wrong.

View of New York City c. 1773. The British captured New York City in 1776. Turning the city

and its environs into their most important base in America, the British heavily fortified the place and

maintained a large garrison in it. The British defenses were scattered however, along a long perimeter

that could be breached by a massed force attacking at one or more locations. Most important, to

Washington, having been disappointed before by the French fleet, it could be attacked without naval

superiority. He viewed the recapture of New York as the Allies primary objective, but he knew that

circumstances might force him to operate against other enemy forces. National Maritime Museum,

London: from the Atlantic Neptune series of charts and coastal views prepared by J.F.W.

Des Barres & Co. for the British Admiralty. In The American Revolution in Drawings and

Prints A Checklist of 1765-1790 Graphics in the Library of Congress. Donald H. Cresswell,

comp., Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1775.

View of New York City c. 1773. The British captured New York City in 1776. Turning the city

and its environs into their most important base in America, the British heavily fortified the place and

maintained a large garrison in it. The British defenses were scattered however, along a long perimeter

that could be breached by a massed force attacking at one or more locations. Most important, to

Washington, having been disappointed before by the French fleet, it could be attacked without naval

superiority. He viewed the recapture of New York as the Allies primary objective, but he knew that

circumstances might force him to operate against other enemy forces. National Maritime Museum,

London: from the Atlantic Neptune series of charts and coastal views prepared by J.F.W.

Des Barres & Co. for the British Admiralty. In The American Revolution in Drawings and

Prints A Checklist of 1765-1790 Graphics in the Library of Congress. Donald H. Cresswell,

comp., Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1775.

While agreeing to the joint land and sea attack against New York, in July, Rochambeau, urged on by his officers, still tried to push for an expedition to join Lafayette, in Virginia. Rochambeau knew that it would be nearly impossible for the Americans to assemble, even a small fraction, of the soldiers necessary, for assaulting such a large and well-defended place as New York. He also knew that he could only request the assistance of the French Navy. Admiral De Barras, commander of the French squadron, in Newport, Rhode Island had shown little inclination to cooperate with anyone.

Having to sell the plan to Admiral De Grasse, commander of the large fleet, ordered north, from the Caribbean, to support the Allied operation, Rochambeau tried again, in June, to convince Washington to head to the Chesapeake. Jealous for the safety of his ships, De Grasse, would in all likelihood, oppose making the very risky forced entry into New York harbor. Under orders not to unnecessarily place his fleet at risk, De Grasse would more likely agree with the southern strategy, because it would give him more room to maneuver.

Admiral, the Comte de Grasse – Another

French veteran with four decades of service, De

Grasse’s decision as to where he would direct his

fleet would determine whether the Allied objective

for 1781 was New York or Virginia. In August, he

gave notice that he was bound for the Chesapeake,

so Washington and Rochambeau marched their

armies south to join him. In September, he dropped

anchor in the Chesapeake and then drove off the

British fleet in the Battle of the Capes. By blocking

the British seaward escape routes, DeGrasse

doomed Cornwallis’ Army. Just six months later,

De Grasse was decisively defeated in the Caribbean,

at the Battle of the Saints, and captured aboard

his flagship, the Ville de Paris. Wikipedia.

Admiral, the Comte de Grasse – Another

French veteran with four decades of service, De

Grasse’s decision as to where he would direct his

fleet would determine whether the Allied objective

for 1781 was New York or Virginia. In August, he

gave notice that he was bound for the Chesapeake,

so Washington and Rochambeau marched their

armies south to join him. In September, he dropped

anchor in the Chesapeake and then drove off the

British fleet in the Battle of the Capes. By blocking

the British seaward escape routes, DeGrasse

doomed Cornwallis’ Army. Just six months later,

De Grasse was decisively defeated in the Caribbean,

at the Battle of the Saints, and captured aboard

his flagship, the Ville de Paris. Wikipedia.

Rochambeau eventually had to inform Washington that he and his officers had been working all along to make the objective of the campaign Virginia. Having already dismissed the idea of relieving the southern states, Washington would have none of it. Angered by this belated challenge, he at first refused to reply. A few days later, he icily told Rochambeau’s emissary, the Duke de Lauzun, that he would only consider operations elsewhere, if the attack on New York became impracticable. Not undone by this rebuke, Rochambeau eventually forced Washington’s hand by convincing De Grasse to head to the Chesapeake.

Excited by the prospects of this campaign, Knox trained his gunners to bombard fortifications. Preparing to besiege New York, the gunners practiced ricochet-firing with their mortars and howitzers. In ricochet-firing, exploding shells, powered by small charges of powder were fired at low angles, so the balls skipped off the ground and rolled into the enemy’s works. Civilians in the area undoubtedly learned quickly to give the testing area a wide berth.

The most important product, of this training, was gunnery tables that enabled them to aim with incredible precision. Theoretically, if the barrel was placed at the same angle with the same charge of gunpowder, the ball would go the same distance each time. That is supposing that each batch of gunpowder met a standard proof; a test to determine the uniformity of its strength.

“The French and English tables of practice [were not of use when used with] American made powder of which some is above proof, some half proof and some no proof at all.” Fine and coarse sieves were needed to bring the powder to a standard proof.

Also included among the battering pieces were 18 and 24 pounder guns which fired solid shot to breach walls and fortifications. There was however, not enough ammunition for a large-scale military operation, unless they could “depend upon the private Magazines of the States and upon our Allies.”

The local powder mills, of Henry Wisner, supplied approximately a ton of gunpowder, over the course of the spring. A fraction, of the estimated 450,000 pounds, of gunpowder, necessary to besiege New York.

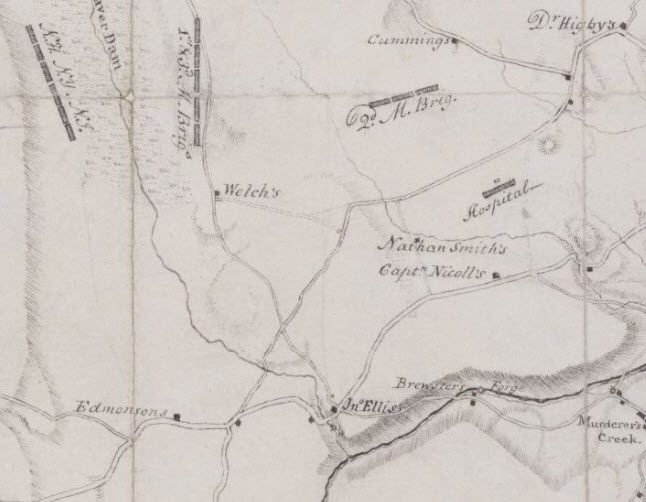

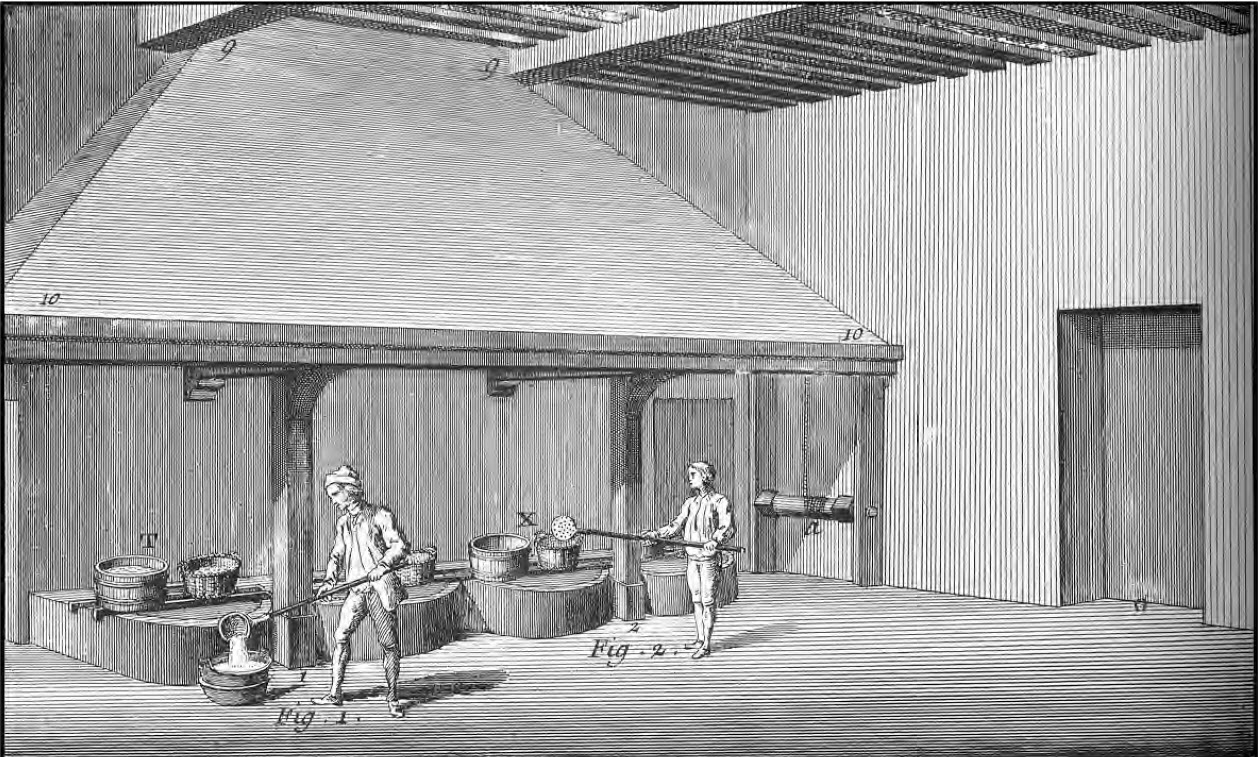

The Method of Refining Salt Petre – Of the elements required for making gunpowder, saltpeter,

made from nitrates, was the most difficult to obtain. Saltpeter combined with charcoal and sulphur produced

gunpowder. A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry, ed., Charles Coulston

Gillispie, 2 vols., New York, 1959 [Selected plates from the 1768 “L’ Encyclopedie” Diderot].

The Method of Refining Salt Petre – Of the elements required for making gunpowder, saltpeter,

made from nitrates, was the most difficult to obtain. Saltpeter combined with charcoal and sulphur produced

gunpowder. A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry, ed., Charles Coulston

Gillispie, 2 vols., New York, 1959 [Selected plates from the 1768 “L’ Encyclopedie” Diderot].

Knox later refined his estimate to over one million pounds. As of July 21, 1780, the Board of War, the committee of Congress responsible for military affairs, reported only 313,300 pounds of gunpowder on hand. Any thought of relying on gunpowder from West Point, had to be balanced with the knowledge that the bomb proof where it was stored was susceptible to flooding. After a May 1781 storm, the barrels of gunpowder in the “lower tier lay several inches under water.”

There was more involved in maintaining gunpowder than just keeping it dry. If the powder barrels were not turned periodically, the nitrates would subside and cause the powder to “cake and be spoiled.”

The procurement of solid shot and shells had degenerated into an opera bouffe. The Board of War, at the end of December 1780, appealed to Congress for money to “satisfy the pressing demands of the Contractors” to relieve them “from a very disagreeable situation.”

The Iron Masters in Pennsylvania and Jersey have completed their contracts for shot and shells, and are incessantly importuning the Board to procure the money... to pay them. They point out ...the positive assurances they received from the Board, that no public embarrassments should prevent their receiving the first payment... Many of them had suffered so severely by their former contracts, that it required the individual interest of some of the members of the Board to prevail on them to undertake the execution of the present agreements, and therefore their reproaches fall on us both in our public and private characters.

Knowing that “General Knox’s Estimates” of the shot and shells required for the “proposed enterprize” to “be undertaken next year” far exceeded the amount on hand, the Board warned Congress that it would “be utterly impossible to prevail on the Iron Masters again to undertake the business if they do not receive what was so solemnly stipulated to be paid them.” Despite the critical need of additional shot and shells for the rapidly approaching start of the campaign season, Congress did not act on the payment until the middle of March.

A scheme was finally worked out with the Admiralty Board to use proceeds from the sale of surplus cannons to pay the iron masters. Desperate to protect their shipping in the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays from privateers and Royal Navy commerce raiders, the merchants of Philadelphia bought the cannons to outfit the 16-gun ship Hyder Ally.

A “detachment of ten Blacksmiths, ten Carpenters and ten wheelwrights from Colonel [Jeduthan] Baldwin’s regiment [of Artillery Artificers, were ordered] to repair to the Park of Artillery.” They were ordered to bring their arms with them. This order was necessary, because the artillery did not always carry weapons for personal defense. Depending on the rest of the army, during the campaign season, the artillerymen were not issued “small arms” at the park, until the beginning of January.

The artificers, busily employed making carriages for the large amount of artillery being assembled from all over the northeast were, however, spared the additional burden of guard duty. Knox ordered “lumber for the carriages at Belknaps Mills”, 2½ miles northeast of the park. This included carriages for the field pieces as well as the larger siege guns. As the carriages were “proofed” or tested design changes were incorporated.

The artificers were given a respite on May 3, 1781. Congress proclaimed that date a day of “fasting, humiliation and prayer” and the army suspended all fatigues. By June, however, they were greatly distressed for lack of rum. “The physicians report that the Artificers (who labour exceedingly hard) are falling sick for want of it.” Their distress must have turned to despair in July when Knox ordered large amounts of additional work that needed to be done immediately.

In a letter to General Knox on July 14, 1781, Lieutenant William Price, from the 3rd Artillery, inquired how many shells were necessary for the 10 inch mortars and 8 inch howitzers. The measurement refers to the muzzle opening. Mortars “throw hollow shells, filled with powder; which, falling on any building, or into the works of a fortification, burst, and their fragments destroy every thing within reach.”

Knox told Captain Thomas Patten from the Artillery Artificer Regiment on July 5, 1781 that:

The mortar beds must be finished immediately, six of the kind at 45 degrees, and six brought down so as to fire at five degrees – these must have trunnion plates and must be strongly bolted.” Besides these there must be three more beds made for the same kind of mortars to be fired at 45 Degrees... If the mortar carriages which will be proved to day shall answer to fire horizontally, six must be finished as soon as possible.

In his manual, Captain William Stevens recorded that “at the siege of Yorktown, in 1781, some 8 inch mortars mounted on carriages constructed similar to travelling carriages with truck wheels, answered a very good purpose.” Truck wheels of garrison carriages were made from cast iron and measure from 12 to 19 inches in diameter, equal in thickness to the caliber of the gun.

Howitzers, mounted on traveling carriages, were short, in order to increase the elevation that their exploding hollow round shells could be fired at. During the development of gunnery tables, in the spring of 1781, tests included the firing of 10 inch mortars, 5½ inch and 8 inch howitzers.

English Bronze 5½ Inch Howitzer cast by

William Bowen, in 1760, at the Royal Gun

Factory, in Woolwich, England. The weight in

the English hundred weight system is marked on

the opposite end of the howitzer, from the muzzle

opening, called the breech. The weight is 4-0-24.

Multiply the first number by 112, the next by 28

and then add the last number to the total of the

other two to determine the weight. The weight of

the howitzer is therefore 472 English pounds. New

Windsor Cantonment State Historic Site.

New York State Office of Parks, Recreation

and Historic Preservation.

English Bronze 5½ Inch Howitzer cast by

William Bowen, in 1760, at the Royal Gun

Factory, in Woolwich, England. The weight in

the English hundred weight system is marked on

the opposite end of the howitzer, from the muzzle

opening, called the breech. The weight is 4-0-24.

Multiply the first number by 112, the next by 28

and then add the last number to the total of the

other two to determine the weight. The weight of

the howitzer is therefore 472 English pounds. New

Windsor Cantonment State Historic Site.

New York State Office of Parks, Recreation

and Historic Preservation.

The propelling charge for mortars and howitzers was placed in the powder chamber located at the bottom of the barrel. The bombardiers tried to lob, bounce or roll the shells into enemy positions, increasing or decreasing the elevation of the barrel and varying the powder charges to hit their target.

The “Artillery Park Magazine” contained ammunition also for 3, 4 and 6 pounder guns or field pieces, both canister and solid shot. The number being the weight of the solid shot. 'Guns' fired more or less on a flat trajectory as opposed to the higher angle fire of the howitzer and mortar. Canister also known as case shot was “formed by putting a great quantity of small iron shot into a cylindrical tin box, called a canister, that fits just fits the bore of the gun. Leaden bullets...[were] sometimes used in the same manner.”

The ammunition for field pieces was either fixed, semi-fixed or unfixed. Fixed ammunition was solid shot or case shot fastened to a wooden bottom with two tin bands and the attached powder charge encased in flannel. Semi-fixed omitted the powder charge and unfixed ammunition was in separate pieces.

The light field guns generally required gunpowder one fourth of the weight of the shot to propel the charge, while the heavy battering pieces used one third.

In July, Knox was readying for shipment to Peekskill, New York, where the army was assembling: six 3 pounders, ten 6 pounders, four 5½ howitzers, and three 8 inch howitzers.

English Bronze 8 Inch Howitzer cast in 1758.

This howitzer was part of the large artillery train

surrendered, by the British, following the Battle of

Saratoga, in 1777. Knox’s Headquarters State

Historic Site. New York State Office of Parks,

Recreation and Historic Preservation.

English Bronze 8 Inch Howitzer cast in 1758.

This howitzer was part of the large artillery train

surrendered, by the British, following the Battle of

Saratoga, in 1777. Knox’s Headquarters State

Historic Site. New York State Office of Parks,

Recreation and Historic Preservation.

To make up for the deficiency of large siege cannons, Washington tried to call in the guns loaned to the states or borrow ones owned by them. From Rhode Island he requested 8 cannons. He applied to Massachusetts for the loan of either 18 or 24 pounders on travelling carriages and “for the delivery of [the] two 13 inch sea mortars” left by the British when they evacuated Boston in 1776. Sent to Boston, to receive the artillery, Colonel John Crane, needed financial assistance from Massachusetts to pay for transporting them to the encampment in New Windsor.

Massachusetts’ and Rhode Island’s compliance with Washington’s requests far exceeded his expectations. At his home, in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Major General Heath recorded in his memoirs on June 23 that: “The marine mortars, and a number of heavy iron cannon, 18 and 24 pounders, were removing from Boston to the North River, New York.”

While showing great deference, in his requests, to the states, Washington could be far less diplomatic in his dealings with individuals. Captain-Lieutenant Jacob Kemper, of the 3rd Artillery, was ordered to Sussex, County, New Jersey “to procure 12 Barrels of Oil”. If the owners would not accept the payment, Kemper was authorized to seize it and bring it to the artillery park.

In July, General Knox wrote to Colonel Crane that “there are carriages made by the Park artificers at New Windsor which will exactly (?) fit the French 18(?) pounders which you have brought with you.” The artificers were ordered to make “12 Garrison carriages” for those cannons. They were also making a garrison carriage, for the 24 pounder cannon, at West Point. Four more English 24 pounder carriages were to be made in order to serve as spares or “supply the deficiencies of those coming from the eastward.” Six extra garrison carriages for English 18 pounders were made as well. As if their burden was not already overwhelming, “20 setts of Waggon Wheels” were necessary to transport the cannons.

They were also to repair the traveling forges used by the blacksmiths, as well as the ammunition wagons and some of the smaller field pieces. The traveling boxes of ammunition carried directly on the artillery carriages were placed in the wagons or in the two wheel carts called tumbrils to protect them from the weather. The cannons, in the park, were put up on skids to protect the carriages from the elements, but elsewhere neglect appeared to be the norm.

Major Bauman, at West Point, wrote to Major General Heath, in January 1781: “Here [West Point] is a number of fine Traveling Carriages for heavy Battering cannon Brought hither from the southward with a Deal of cost and labour, which for want of paint and covouring (?) are now rotting here!” Major William Perkins, from the 3rd Artillery, responsible for forwarding the artillery and ordinance, from New England, remarked that: “Eight Eighteen Pounders are goan by Water to Harford, their wont be but about Four or five Field Carriages of them fit to send.”

A laboratory was established in camp to prepare the shells, fuses, tubes and port-fires for the campaign. Shells were made in foundries, by pouring molten iron into an iron mold, with the core filled with sand. This produced a hollow ball. After cooling, the forms and sand were removed. Powder was poured inside the shell and a fuse was added. Fuses were usually made of hollowed out beech wood and received a composition of sulphur, saltpeter and meal powder that would burn at a fixed rate. The distance to the enemy was calculated and the fuses were cut so the shell would explode in the enemy’s midst, sending deadly fragments in every direction.

Tubes were tin cylinders filled with mealed powder moistened with spirits of wine that went into the vent, at the top, of the cannon, to complete the path to the powder placed inside the barrel. Port-fires, similar to modern car flares, were capable of firing the cannon under very wet conditions. For better coordination, of widely separated attacks, they made up some signal rockets.

In July, Knox led the 2nd Artillery south to join General Washington, in an expedition, not to New York, but instead to a small village, on the coast of Virginia, in which tobacco was traded, named Yorktown. Admiral Degrasse, commanding the large French naval and ground force sailing north from the Caribbean, gave notice, in August 1781, that he was bound for the Chesapeake, so Washington and Rochambeau marched south to join in the attack on British forces, in Virginia.

The 3rd Artillery must have watched with envy as their comrades, in the 2nd, went to Yorktown, while they remained in the Highlands guarding West Point.

During the siege of Yorktown, the 2nd looked back with satisfaction at the training done at New Windsor. They could now drop exploding shells “just over the enemy’s parapets destroying them where they thought themselves most secure.”

The French and American victory, at Yorktown, was the result of unprecedented cooperation and daring. French Admiral De Grasse’s moral courage in leaving the Caribbean virtually defenseless to achieve the mass of ships necessary to achieve naval superiority on the Atlantic seaboard and block any rescue attempt by the British Royal Navy made the campaign possible. Combined with the unprecedented cooperation between Congress and the states to supply the Continental Army and provide for its transportation from New York’s lower Hudson Valley, to Virginia, these actions proved decisive.

No small feat was the assembly of the American siege train of artillery that accompanied the Army to Virginia. When finally assembled, in Virginia, the American siege train “consisted of more than thirty pieces of cannons or mortars of a large bore.” This responsibility sorely tasked everyone involved in the endeavor, most of all, the officers and men of the artillery encamped at New Windsor, New York.

The burden fell heaviest on the artillery commander General Knox. “One cannot too much admire the intelligence and activity with which he collected from all quarters, transported, disembarked, and conveyed to the batteries the artillery train intended for the siege.”

Next Issue of Journal!

The Next Issue of the OCHS Journal is now accepting articles for consideration.

Authors

More guidelines for authors

Classics from the Journal

NEW!! The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part I

by Michael S. McGurty

NEW!! The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part II

by Michael S. McGurty

NEW!! Orange County Militia During the American Revolutionary War

by Alan Aimone

George Washington's Masonic Activities in Orange County

by Andrew J. Zarutskie

Prisoners of War in Goshen

by Harold J. Jonas

John Robinson of Newburgh

by Margaret V. S. Wallace

The Battle of Fort Montgomery

by Donald F. Clark

Role of Regional Revolutionary Women

by Michelle P. Figliomeni

Robert R. Burnet (1762-1854)- The Last Continental Officer

by Alan C. Aimone and Barbara A. Aimone

The Revolutionary Soldier in Washington's Army

by Edward C. Cass

Technical Communication in the Amercan Revolution

by Carol Siri Johnson

New Windsor Cantonment

by E. Jane Townsend

Sidman's Bridge

by Kenneth R. Rose

Corridor Through the Mountains

by Richard Koke

Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck and "The Sybil"

by Amy Kesselman

The Store at Coldengham (1767-1768)

by Jay A. Campbell