Revolution in the Highlands

The Story of the Battle of Fort Montgomery

Donald F. Clark

[Editor's Note: This article appeared in the 1979 Issue of the Journal of the Orange County Historical Society. It is being republished on the website as part of the ongoing activities surrounding the 250th Anniversary of the Revolutionary War. The footnoted version is contained in the 1979 Journal which is available for purchase. JAC]

====================

The skirmishes at Lexington and Concord opened the "shooting war" of the American Revolution on the 19th of April 1775. The very next month, on May 25th, 1775, the Continental Congress resolved "that a post be . . . taken in the Highlands on each side of Hudson's River and batteries erected in such a manner as will most effectually prevent any vessels passing .... "

On May 30th, 1775, the New York Provincial Congress ordered Colonel James Clinton and Mr. Christopher Tappan "to go to the Highlands and view the banks of Hudson's river there; and report to this Congress the most proper place for erecting one or more fortifications; and likewise an estimate of the expenses that will attend erecting the same." Thus began the efforts to fortify the Hudson Highlands, over a year before the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

After James Clinton and Christopher Tappan visited the Highlands and made their report, the first fortification attempts were made at Constitution Island. However, by December of 1775, it was recommended that a strong fortification be built opposite Anthony's Nose, on Popolopen Creek.

On the 31st of December 1775, General Richard Montgomery was killed in his attempt to capture Quebec at night in a driving snowstorm. James Clinton was with Montgomery. It was natural that the new fortification was named Fort Montgomery. Incidentally, at Quebec, a brilliant young Colonel (himself wounded) took command of the remnant of the American army after the death of Montgomery. His name was Benedict Arnold.

General Richard Montgomery

General Richard Montgomery

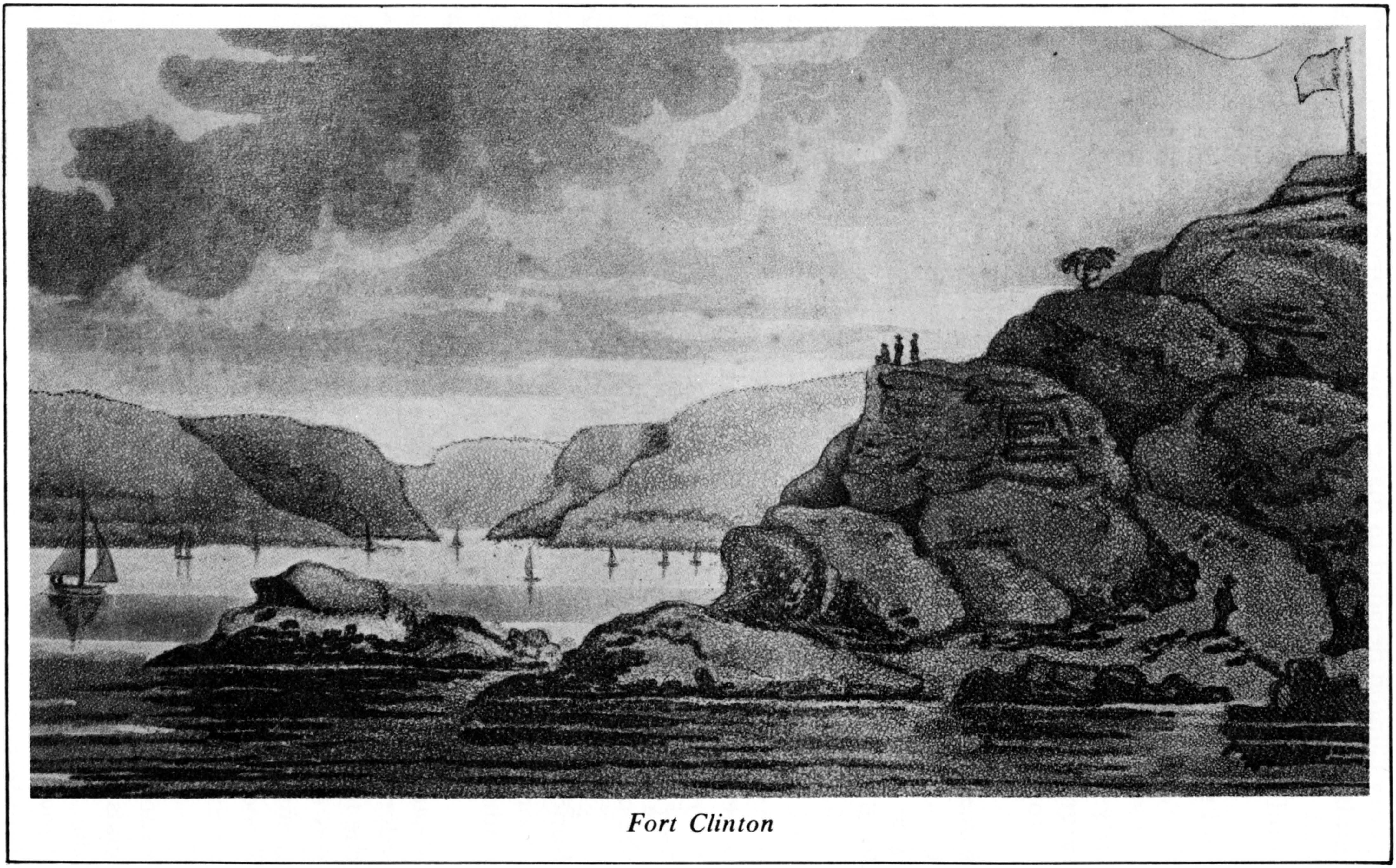

On the 1st of June 1776, it was recommended that another fort be erected on the south side of Popolopen Creek. This was called Fort Clinton. Meanwhile, George Clinton, younger brother of James, was representing New York in the Second Continental Congress at Philadelphia. The brothers were sons of Charles Clinton, leader of the Scotch-Irish settlement of Little Britain in New Windsor. The father and both sons had served in the French and Indian War. In the summer of 1776, George was chosen to serve in the New York Provincial Congress and was given command in the Highlands, with the rank of Brigadier-General. The Clinton brothers then worked together to strengthen the defenses, including the construction of the first Hudson River chain and boom, from Fort Montgomery to Anthony's Nose.

Fort Clinton

Fort Clinton

The Americans desperately tried to destroy British ships in the lower Hudson. On the 16th of August 1776, an effort was made to destroy two British ships, the Phoenix and the Rose. The Americans used fire ships and galleys, but the British successfully warded off the attack. In a further effort to obstruct navigation of the river, a chevaux-de-frize was constructed at Pollopel Island (later Bannerman's). This device consisted of wooden cribs sunk in the channel, with iron-tipped spears pointing upward, at an angle, to prevent passage of ships.

The year 1777 was a fateful one in the Hudson Valley. Inasmuch as the Declaration of Independence had affirmed that the colonies were free and independent states, it had become necessary for them to establish state governments. The representatives of the State of New York met at Kingston and adopted a constitution. Shortly after the adoption of this constitution, an election was held. So great was the popularity of George Clinton that he was elected as both Governor and Lieutenant Governor. He accepted the office of Governor, continuing to serve as a general.

The British ministry had its grandiose scheme to divide and conquer the rebellious colonies. Burgoyne was to come south from Canada (by way of Lake Champlain) to Albany. St. Leger was to advance on Albany by way of the Mohawk Valley. Sir William Howe was to move up the Hudson Valley to Albany. Burgoyne and St. Leger tried to follow the plan. Howe, apparently thinking he had discretionary powers, moved toward Philadelphia, not Albany. He left Sir Henry Clinton in command of the British forces at New York City. Sir Henry was a distant cousin of the Little Britain Clintons and a son of another George Clinton, Admiral of the White Squadron and Governor of the Province of New York in the 1740's.

St. Leger met resistance in the Mohawk Valley and never reached Albany. Burgoyne ran into trouble near Saratoga and soon found himself in a desperate situation. Meanwhile, Sir Henry Clinton decided to make a diversionary expedition up the Hudson River. On the 25th of September 1777, fifty British ships had arrived in New York harbor, bringing supplies and troop reinforcements.

In a few days, Sir Henry and Commodore William Hotham had their joint army-navy expedition under way. Clinton's "little army," as he called it, consisted of about three thousand men, a sizeable force for those days. The navy provided the Preston (a fifty-gun warship); two frigates (the Mercury and the Tartar), a large number of flatboats and batteaux, and a "flying squadron" of row-galleys under the command of Sir James Wallace.

Governor George Clinton received word of the British reinforcements and the British movements, and hastened to join General James Clinton at Fort Montgomery and Fort Clinton. The brothers could muster only about six hundred men, mostly local militia.

The British proceeded up the river as high as King's Ferry and Verplank's Point and landed a considerable force on the east side of the river at daybreak on Sunday, the 5th of October. The Americans retreated from Verplank's Point, leaving a twelve-pounder cannon behind them. That evening, George Clinton, at Fort Montgomery, sent Major James Logan southward through the mountains to reconnoitre.

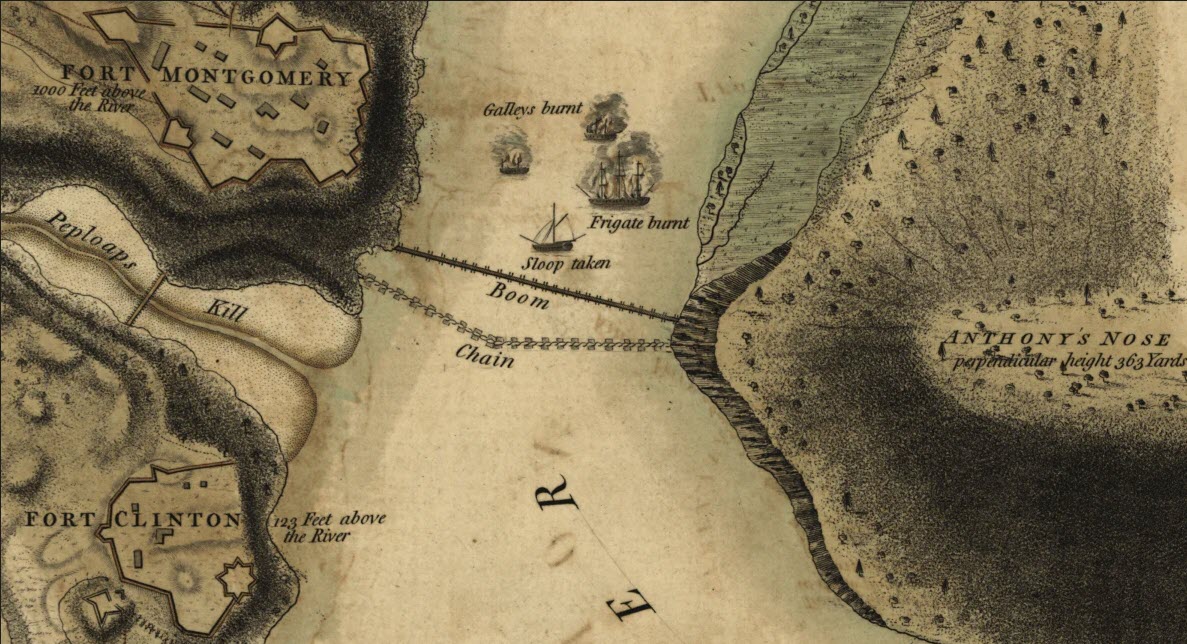

Plan of Attack on the Forts Clinton and Montgomery as drawn by John Hill, Engineer in the British Arrmy

Plan of Attack on the Forts Clinton and Montgomery as drawn by John Hill, Engineer in the British Arrmy

At dawn on the 6th of October, leaving only about four hundred to hold Verplank's Point on the east shore, the British troops were landed at Stony Point on the west shore of the river, under cover of a heavy fog.

Major Logan returned to George Clinton that morning at about nine o'clock and reported the British had landed a considerable force, but he could not estimate numbers because of the fog. As soon as this information was received, Governor Clinton dispatched Lieutenant Paton Jackson and a small detachment on the Haverstraw Road, but Jackson got only as far as Doodletown when he encountered British troops and there was an exchange of musket-fire.

From British accounts of the battle, it is known that this advance guard of five hundred regulars and four hundred provincials, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Mungo Campbell of the 52nd Regiment, with Colonel Beverly Robinson of the Provincials under him, began its march to occupy the pass of Dunderberg. This advance guard, after it had crossed the Dunderberg, and gotten to Doodletown, proceeded around the west side of Bear Mountain and fanned out in the rear of Fort Montgomery.

Meanwhile, General John Vaughan, with twelve hundred men, continued to march from Doodletown toward Fort Clinton. Major-General William Tryon, with the remainder, made up the rear-guard, to guard the pass at Dunderberg and maintain communication with the fleet.

George Clinton sent out detachments on the road to Doodletown, south of Fort Clinton, and on the road to the Forest of Dean, west of Fort Montgomery, but they were able to do little to slow the approach of the British.

The attack on the forts began at two o'clock in the afternoon and continued, with few intervals until about five o'clock, when Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell approached Fort Montgomery under a flag of truce, demanding surrender of the fort. The Americans refused, and Colonel Campbell was killed as soon as fighting was resumed. The battle continued until dusk, when the British "forced the works on all sides" and captured both forts. Many of the Americans escaped under cover of darkness. Governor George Clinton managed to escape by boat to the east side of the river. General James Clinton, although he had received a bayonet wound, also managed to escape.

Attack on Fort Montgomery

Attack on Fort Montgomery

Sir Henry Clinton described Fort Clinton in these words: .. "a circular height, defended by a line for musketry, with a barbette-battery in the center (of three guns), and flanked by two redoubts; the approaches to it through a continued abatis of four hundred yards, defensive every inch, and exposed to the fire of ten pieces of cannon."

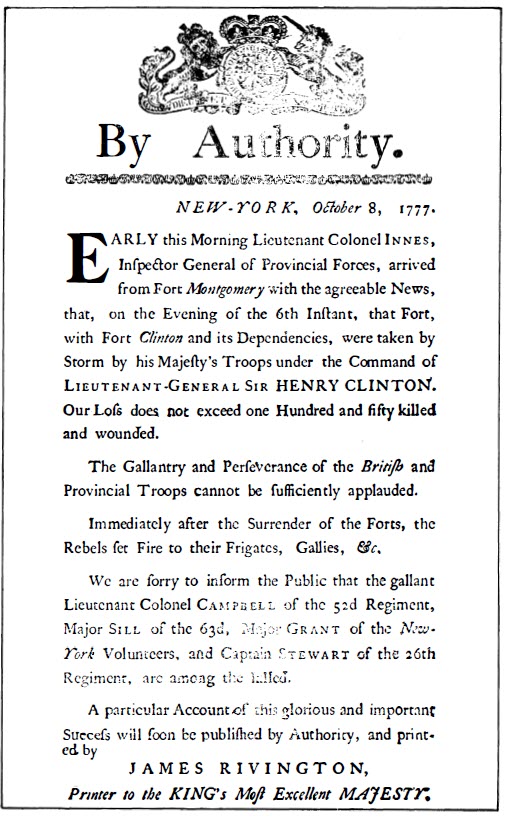

Two days after the battle, James Rivington, New York City printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty, published a poster or broadside, announcing what the British called "this glorious and important Success." In the words of the broadside: "Early this morning Lieutenant Colonel Innes, Inspector General of Provincial Forces, arrived from Fort Montgomery with the agreeable news, that, on the evening of the 6th Instant, that Fort, with Fort Clinton and its Dependencies, were taken by Storm by his Majesty's Troops under the Command of Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Clinton."

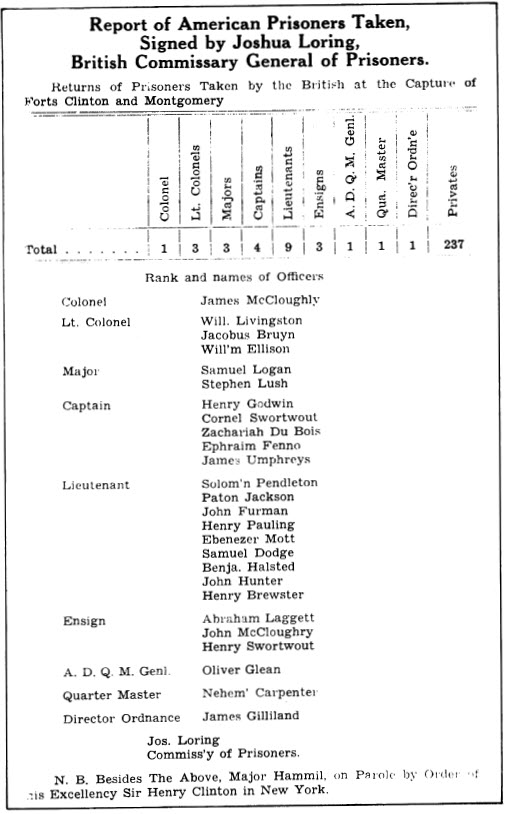

The British reported that about one hundred Americans were killed, and two hundred and sixty-three were taken prisoner (26 officers, 237 rank and file). The British casualties totaled one hundred and eighty-eight. Forty were killed (7 officers, 3 sergeants, 30 rank and file). In addition, Count Grabowski was killed. He was a Polish nobleman acting as aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Clinton. One hundred and forty-two were wounded (11 officers, 4 sergeants, 1 drummer, 126 rank and file). Five were listed as missing (all rank and file).

The Americans lost sixty-seven cannon and large quantities of other military stores. Two American warships, the Montgomery and the Congress, were burned by the Americans to prevent capture by the British. These two frigates had been built at Poughkeepsie as New York's quota of the thirteen ordered by the Continental Congress.

Two American galleys were burned also by their own crews, and one armed sloop, of ten guns, was captured by the British. After the battle, British engineers dismantled the Fort Montgomery chain and boom. Commodore Hotham said the construction of both gave "strong Proofs of Labour, Industry and Skill."

As previously mentioned, it was Lieutenant-Colonel Mungo Campbell, of the 52nd Regiment, who led the column which stormed Fort Montgomery, and was killed at the head of his troops. George Clinton tells the story in this way. The British began the attack about two o'clock in the afternoon, and continued until about five, when a British officer appeared with a flag of truce. Lieutenant-Colonel William S. Livingston, a prominent young aristocrat, who probably had the finest horse and best uniform, was sent out to meet the British Officer, who identified himself as Col. Campbell, and said that he came to demand the surrender of the fort. Young Livingston arrogantly replied that he had no authority to deal with him but, if the British would surrender themselves prisoners of war, they might depend upon being well treated; and if the British did not choose to accept these terms, they might renew the attack as soon as he, Livingston, had returned within the fort, the Americans being determined to defend it to the end.

The British renewed the battle, and Col. Campbell was killed in the first attack, probably by some local woodsman with a well-aimed bullet from his squirrel rifle. And what happened to the brash young Colonel Livingston? The British captured him and held him prisoner until he escaped some time later. He wrote to George Clinton and said: "In the Fort I lost my Horse, Saddle, Great-Coat, Sword and Pistols, and where I can replace them I know not. Walk to the Regiment, I cannot. I must have a Horse or Stay at Home." Then he proceeded to imply that the local residents were horse-thieves. "The Enemy I am confident took no Horses down to York with them, so that I am persuaded the People in that Neighborhood must be in possession of mine." Then he added what we might call his punch line: "As soon as I can purchase a Horse or find a Tory who I can, with propriety, take one from, I hope to see you."

Not all of the regiments were typical British redcoats. One was the 26th Regiment of Cameron Highlanders. It is possible to imagine this regiment going into battle to the accompaniment of the skirl of the bagpipes.

On Tuesday, October 7th, the day after the battle, Sir Henry Clinton and Commodore Hotham sent a flag of truce up the river to Fort Constitution to demand the surrender of the small garrison stationed there but the British truce party was met with gunfire and returned to Fort Montgomery.

On Wednesday, October 8th, the British sent a sizeable force to attack Fort Constitution but found it had been destroyed by the Americans and abandoned. Sir Henry sent a marauding party to Continental Village, back of Peekskill, and destroyed large quantities of American supplies, and barracks for fifteen hundred men. He sent Sir James Wallace and General Vaughan up the river. They encountered resistance at Kingston and burned the whole town with the exception of one house.

Burgoyne at Saratoga, hopelessly surrounded so he could neither advance nor retreat, surrendered his entire army on the 17th of October. Nine days later, Sir Henry destroyed all that remained of the Highland Forts and returned to New York. He had held the Highlands for twenty days.

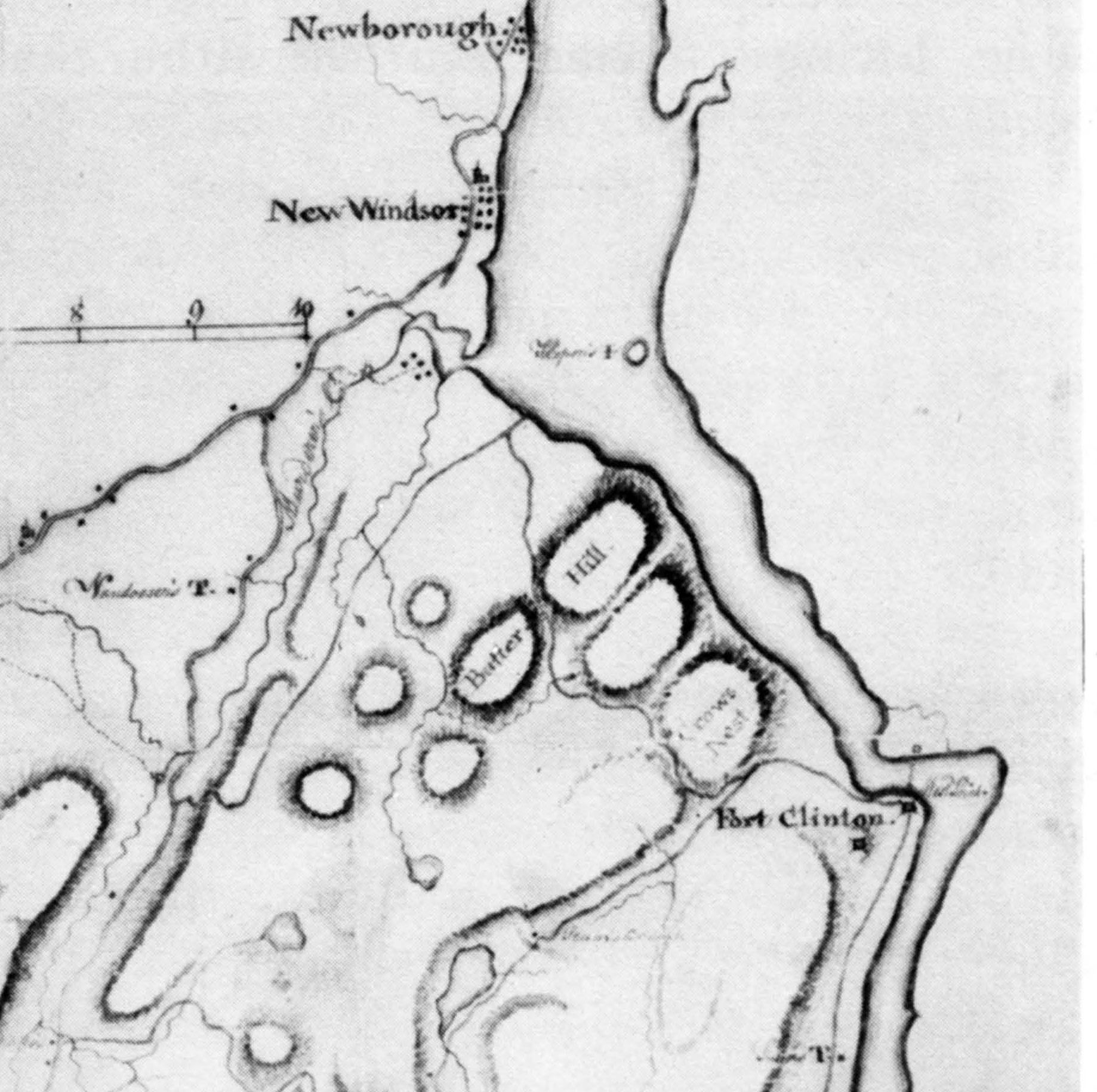

Early in 1778, the Americans occupied West Point and fortified it for the first time, and placed the second Hudson River chain across the river from West Point to Constitution Island.

Portion of a map titled "Plan of the country contiguous to West Point, Smith's Clove, ...", survey by Robt. Erskine, 1779. Showing the 'new' Fort Clinton (on the point), Fort Putnam (the black square under the 'o' in 'Clinton', and the 'new' chain across the river.

Portion of a map titled "Plan of the country contiguous to West Point, Smith's Clove, ...", survey by Robt. Erskine, 1779. Showing the 'new' Fort Clinton (on the point), Fort Putnam (the black square under the 'o' in 'Clinton', and the 'new' chain across the river.

West Point became a fortified stronghold, and was never challenged by British forces. In July of 1779, Anthony Wayne used the Fort Montgomery area as a base of operations for his spectacular attack on the British at Stony Point.

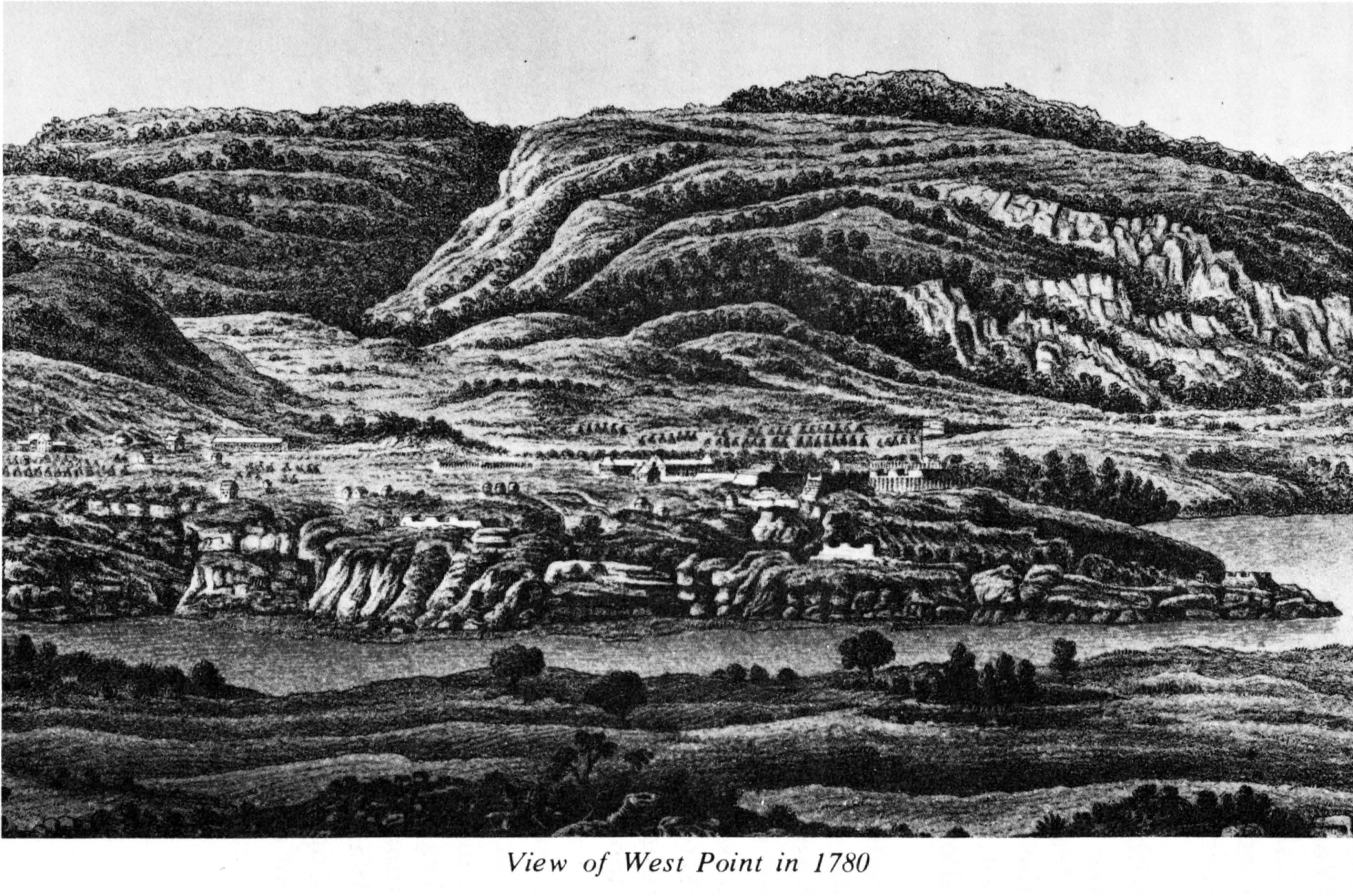

West Point in 1780 showing rows of tents

West Point in 1780 showing rows of tents

The war dragged on, but for all practical purposes, it ended with the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781. However, the definitive Treaty of Peace did not take effect until 1783. Meanwhile, Washington had his headquarters at Newburgh and the final encampment of the American Army was at New Windsor. In June of 1783, most of the soldiers were furloughed and allowed to go home.

On the 25th of November 1783, the last British troops left New York City and General Henry Knox marched in to keep order as the British left. Governor George Clinton transmitted the formal thanks of the council and General Knox responded by letter dated at West Point, the 22nd of December 1783: "I have received your Excellency's favor of the 18th instant enclosing an Act of the Council, expressive of their thanks to myself and the officers and men of the Continental troops who have lately been upon duty in the City of New York."

The British troops were gone. American independence had been secured. George Clinton continued as Governor of New York for many years, then was elected Vice-President of the United States and, while serving in that office, died in Washington, D.C., in 1812. It may not be an exaggeration to say that George Clinton was to the State of New York what George Washington was to the nation. And the Hudson Highlands, no longer echoing the sound of gunfire, became a favorite subject for artists and printmakers.

Next Issue of Journal!

The Next Issue of the OCHS Journal is now accepting articles for consideration.

Authors

More guidelines for authors

Classics from the Journal

NEW!! The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part I

by Michael S. McGurty

NEW!! The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part II

by Michael S. McGurty

NEW!! Orange County Militia During the American Revolutionary War

by Alan Aimone

George Washington's Masonic Activities in Orange County

by Andrew J. Zarutskie

Prisoners of War in Goshen

by Harold J. Jonas

John Robinson of Newburgh

by Margaret V. S. Wallace

The Battle of Fort Montgomery

by Donald F. Clark

Role of Regional Revolutionary Women

by Michelle P. Figliomeni

Robert R. Burnet (1762-1854)- The Last Continental Officer

by Alan C. Aimone and Barbara A. Aimone

The Revolutionary Soldier in Washington's Army

by Edward C. Cass

Technical Communication in the Amercan Revolution

by Carol Siri Johnson

New Windsor Cantonment

by E. Jane Townsend

Sidman's Bridge

by Kenneth R. Rose

Corridor Through the Mountains

by Richard Koke

Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck and "The Sybil"

by Amy Kesselman

The Store at Coldengham (1767-1768)

by Jay A. Campbell