The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781

By Michael S. McGurty

Part I - "answered a very good purpose"

[Editor's Note: This article appeared in the 2008 Issue of the Journal of the Orange County Historical Society. It is being republished on the website as part of the ongoing activities surrounding the 250th Anniversary of the Revolutionary War. The footnoted version is contained in the 2008 Journal which is available for purchase. JAC]

====================

Introduction

During the siege of Yorktown, Virginia, in the fall of 1781, Major General, the Marquis de Lafayette, impressed by the performance of the Continental artillery proudly remarked to Major Samuel Shaw, aide de camp, to the artillery commander, Brigadier General Henry Knox: “Sir you fire better than the French. On my honor it’s the truth. Everyone know[s] the progress of your artillery is one of the wonders of the Revolution.” Even after taking into account the French penchant for flattery, this development was truly remarkable.

Mortar at Yorktown Battlefield. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service.

Mortar at Yorktown Battlefield. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service.

Formed just six years before from militia companies, like the Providence [Rhode Island] Train of Artillery, the artillery matured into the most effective arm in the Continental service. At Yorktown, the effectiveness of the American artillery combined with the equally capable performance of the French gunners, so suppressed the British that they “dare not show a gun.” Overwhelmed by the iron storm that mercilessly poured its destruction on their works, the British surrendered. When told of the surrender of General Cornwallis’ Army, at Yorktown, British Prime Minister Lord North exclaimed repeatedly: “Oh God! It is all over!”

Had anyone the year before opined that in the next campaign America would secure its independence with a decisive victory, he would have been thought mad or at best chimerical. Prior to Yorktown, the situation for the United States, if not desperate, was far from optimistic. The Revolution had reached its nadir the previous year. In May 1780, the American southern army, trapped inside Charleston, South Carolina, surrendered to British forces. Another force, sent by General Washington to retrieve American fortunes in the south, was routed at Camden, South Carolina, in August. Following that victory, the British were poised to overrun the entire southern half of the country. The treason of Benedict Arnold, discovered in September, shook what little faith Americans still had in their leaders. The bitter recriminations of financial impropriety between the American representatives, in Europe, delighted the republic’s enemies and chagrined her friends. “The revelation of widespread corruption in the federal service at home also left a residue. It contributed heavily to the perilous demoralization of the country…., when the American cause seemed on the verge of disaster.”

The American people were not blameless. Gone were the republican virtues of sacrifice and suffering for the common good, nostalgically recalled as “the spirit of 1776”. Among them a spiritual rot had set in. Major General Nathanael Greene lamented that: “The loss of morals and the want of public spirit leaves us almost like a rope of sand.” The United States’ finances were in a ruinous condition and the growing number of mutinies showed that the legendary American soldier perseverance in the face of adversity was starting to waver.

Possibly most disheartening, was that the entry of France, into the conflict, in 1778, had not been the panacea that Americans expected it to be. Initially filled with strategic promise, the alliance had produced little, but discord, which resulted from the botched attacks made by the combined French and American forces at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1778, and Savannah, Georgia, in 1779. The following year, an French and American attack, on New York City, never got beyond the planning stage. Despite these disappointments, Washington knew everything depended on the French. With no other choice than to watch and wait for their often-less than cooperative ally, the Northern Continental Army encamped around West Point, New York, during the winter of 1780-1781, and prepared for the next campaign season. The heaviest burden fell on the Continental artillery soldiers at New Windsor, New York.

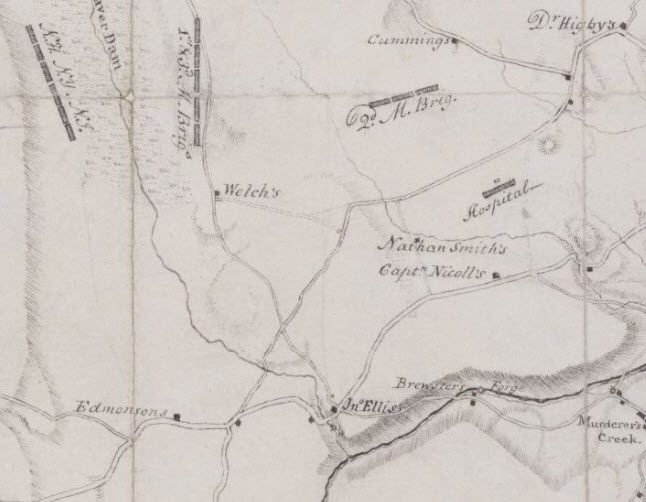

A portion of a Simeon Dewitt Map – “The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity

for 1783.” The hospital building shown served as artillery huts in 1781. General Knox made his headquarters,

south of the camp, at the house marked “Jn Ellis” (John Ellison). New Windsor and the Hudson River are to the right of this map, Snake Hill is just to the north. New-York Historical Society Digital Collection. Click on image to enlarge.

A portion of a Simeon Dewitt Map – “The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity

for 1783.” The hospital building shown served as artillery huts in 1781. General Knox made his headquarters,

south of the camp, at the house marked “Jn Ellis” (John Ellison). New Windsor and the Hudson River are to the right of this map, Snake Hill is just to the north. New-York Historical Society Digital Collection. Click on image to enlarge.

They were given the responsibility for assembling and preparing the heavy train of artillery, without which, attacking the heavily fortified New York City, would not be possible.

In the beginning of December 1780, over 300 soldiers from the 2nd and 3rd Continental Artillery Regiments began constructing an artillery park in New Windsor, New York, behind the protective shield of the Hudson Highlands and West Point. Both regiments sent eight of their companies to New Windsor. The other four companies from each regiment were at West Point. There was a handful of men from the 4th Continental Artillery as well - owing to a pique among the officers of the 4th over rank that was temporarily resolved by attaching two of their companies to the 2nd. Washington ordered this ended because: “... as [Colonel John] Lambs regt. [2nd] has two Companies more than the establishment allows, and [Colonel Thomas] Proctors [4th] wants two to compleat it.”

In January, the artillery regiments were reduced to 10 companies. The 2nd Continental Artillery had soldiers from New York, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and from what is now known as Vermont. The 3rd was from Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The 4th came from Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maryland. This does not mean that one would not find soldiers from elsewhere, but generally they were from the states credited to the regiment.

The Continental Army fielded four artillery regiments during the war. The authorized strength of an artillery regiment was 729. The regiment consisted of one colonel, one lieutenant colonel, one major, a surgeon and surgeon’s mate, one sergeant-major, one quartermaster-sergeant, one fife-major, one drum-major and twelve companies.

Each company consisted of one captain, one captain lieutenant, one first lieutenant, three second lieutenants, six sergeants, six bombardiers, six corporals, six gunners, two drummers and two fifers and 28 matrosses. Bombardiers prepared the artillery shells and fuses and serviced the howitzers and mortars that fired them. Matrosses assisted with sponging, loading and firing the guns. “They also man[ned] the dragropes affixed to hooks at the end of each axle to move the field artillery on the battlefield.”

Given the difficulty of recruiting the army to levels anywhere near full strength, Congress, on October 3, 1780, reduced the size of the artillery regiments to 9 companies of 65 non-commissioned officers and matrosses. The tenth company, however, was retained at the request of General Washington. Also, the onus for filling the 2nd was given exclusively to New York and for the 3rd entirely to Massachusetts. The reorganization took effect on January 1, 1781.

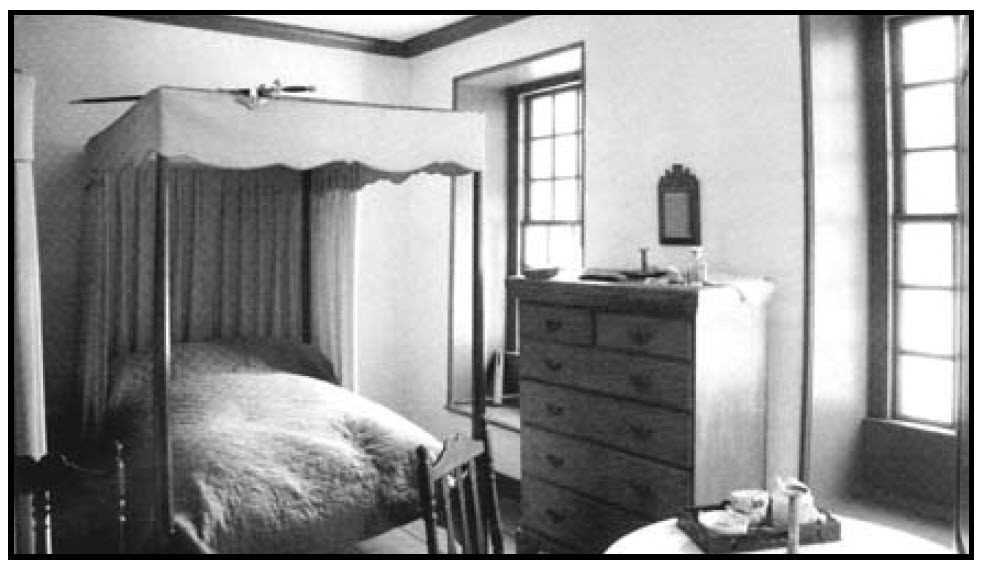

Continental Artillery commander Brigadier General Henry Knox established his headquarters nearby, at the elegant 1754 stone house, of merchant miller John Ellison.

The guest bedroom at Knox’s Headquarters.

This room and the one in the hallway, which no

longer exists, were probably the two rooms rented

by General Knox. Major Shaw probably stayed in

the small room in the hallway. Knox’s Headquarters

State Historic Site, New York State

Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

The guest bedroom at Knox’s Headquarters.

This room and the one in the hallway, which no

longer exists, were probably the two rooms rented

by General Knox. Major Shaw probably stayed in

the small room in the hallway. Knox’s Headquarters

State Historic Site, New York State

Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

Shortly thereafter, his wife Lucy joined him, along with their young daughter Lucy and infant son Henry. Approximately six feet tall and tipping the scales at 280 pounds, Knox was “very fat, but very active, and of a gay and amiable character.” Underneath that bulky façade was also an indefatigable spirit, affability and lead by example style that inspired subordinates.

Brigadier General Henry Knox, a copy after

Gilbert Stuart by Albert Nemethy, 1962 - A

Boston bookseller before the war, Henry Knox

learned artillery theory by reading the latest treatises

on the subject in his shop. He became one of

Washington’s most able and loyal lieutenants.

New Windsor Cantonment State Historic

Site. New York State Office of Parks, Recreation

and Historic Preservation.

Brigadier General Henry Knox, a copy after

Gilbert Stuart by Albert Nemethy, 1962 - A

Boston bookseller before the war, Henry Knox

learned artillery theory by reading the latest treatises

on the subject in his shop. He became one of

Washington’s most able and loyal lieutenants.

New Windsor Cantonment State Historic

Site. New York State Office of Parks, Recreation

and Historic Preservation.

Head of the artillery, since November 1775, Knox was described by General Washington as: “one of the most valuable officers in the service” who after “combatting almost innumerable difficulties… placed the artillery upon a footing that does him the greatest honour.” The Chevalier de Chastellux, a French major general and author of Travels in North America in 1780, 1781 and 1782 concurred with the belief of Washington and others that the artillery “could not have been placed in better hands.”

Sometimes called by his detractors, the Philadelphia nabob, because of his notorious appetite for the finer things in life and lavish manner of entertaining, Knox fitted his headquarters with a suite of furniture that one would have expected to encounter in the homes of the first families of the nation. At his winter headquarters, near Morristown, New Jersey, over the winter 1778-79, Knox received : “8 mohackny chairs, 1 D[itt]o arm D[itt]o, 1 D[itt]o close stool, 1 D[itt]o Breakfast Table, 1 D[itt]o washand stand”, brass mounted fireplace implements, and various bedding. The actual bedstead, with its reinforcing iron rods to support Knox’s weight, was left behind in New York. Knox was reminded however, that the artificers, skilled tradesmen in the artillery corps, could easily make up another one. The furniture was placed in storage when the Army was in the field.

Though he found much to like about Henry Knox, Chastellux was not as charitable in his description of Lucy. Confiding in the privately-printed edition of his journal, Chastellux described Lucy Knox’s pathetic attempt to ape the latest European fashions and coiffures: “Her attire was ridiculous without being neglected; she had made of her black hair a pyramid which rose a foot above her head; this was all decked out with scarves and gauzes in a way that I am unable to describe.” Vivacious and just as heavy as her husband, Lucy was estranged from her affluent Tory family, who had fled the country at the outbreak of the war.

Major Samuel Shaw, from Colonel John Crane’s 3rd Artillery, was Knox’s aide de camp. Shaw spent part of the winter, in Boston, on furlough. Two soldiers were transferred from companies elsewhere to complete his military family; one served as the General’s waiter while the other’s wife tended to Mrs. Knox “pour convenience de la femme.” He had a guard of six that was increased to twelve in February. Knox stayed at his “friend Ellisons” several times during the war.

Prior to the move of the artillery to its winter cantonment or encampment at New Windsor, Washington ordered the head of the quartering party, Lieutenant Colonel Ebenezer Stevens, of the 2nd Artillery, to:

look out for a convenient piece of Ground for hutting the Number of Officers and Men who will be attached to the Park this Winter... In doing this, you are to pay particular attention to the dryness of the soil; sufficiency of Wood for Building and firing, and conveniency of water. The position to be as near New Windsor as the circumstances of Ground, Wood and Water will permit. Having pitched upon the position, you will set the men to cutting Logs of proper lengths for building, and splitting Shingles.

Lieutenant Colonel Ebenezer Stevens, 2nd

Continental Artillery by Edward Savage. Commander,

of the artillery, for the Northern Department,

in 1776, he participated in the Saratoga campaign

the following year. He was commander, of

the artillery park, during the absence of 2nd Artillery

commander Colonel John Lamb and 3rd Artillery

commander Colonel John Crane. Collection

of the New-York Historical Society.

Lieutenant Colonel Ebenezer Stevens, 2nd

Continental Artillery by Edward Savage. Commander,

of the artillery, for the Northern Department,

in 1776, he participated in the Saratoga campaign

the following year. He was commander, of

the artillery park, during the absence of 2nd Artillery

commander Colonel John Lamb and 3rd Artillery

commander Colonel John Crane. Collection

of the New-York Historical Society.

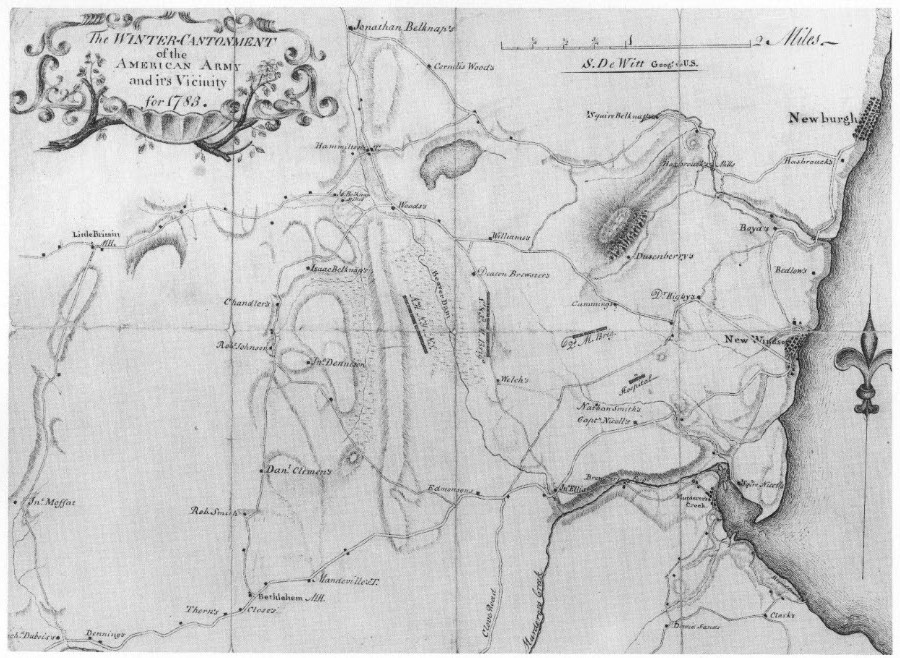

The Simeon Dewitt Map – “The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity

for 1783” by Simeon Dewitt, Geographer to the Continental Army. The artillery huts were later

made into the hospital shown in the eastern section of the map. General Knox made his headquarters,

south of the camp, at the house marked “Jn Ellis” (John Ellison). Washington’s headquarters was located

at the Thomas Ellison house in New Windsor. Belknap’s Mills that produced the boards for the officer

huts and the artillery carriages was located 2 1/2 miles northeast of the artillery camp.

Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Click to Enlarge.

The Simeon Dewitt Map – “The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity

for 1783” by Simeon Dewitt, Geographer to the Continental Army. The artillery huts were later

made into the hospital shown in the eastern section of the map. General Knox made his headquarters,

south of the camp, at the house marked “Jn Ellis” (John Ellison). Washington’s headquarters was located

at the Thomas Ellison house in New Windsor. Belknap’s Mills that produced the boards for the officer

huts and the artillery carriages was located 2 1/2 miles northeast of the artillery camp.

Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Click to Enlarge.

First settled in the late seventeenth century, New Windsor was a thriving community of approximately 1,300 when the Continental artillery established its cantonment. This number included slaves and refugees from British occupied areas. Located on the west side of the Hudson River, just south of Newburgh, New Windsor was astride the trade routes heading into New England and those via the water to Albany and New York City. It had the only glass manufactory in the county. To the west of the village, along rolling hills, there were farms, orchards and woodlots. The terrain is dominated by Snake Hill, the granite eminence that rises more than 200 feet above the surrounding countryside. Several gristmills and at least one sawmill were located along the many streams in the vicinity. Brewster’s Forge, on Murderers Creek, made the large iron clevises that held together the links of the great chain at West Point.

Numerous soldiers had moved through the town before, but this was the first time any appreciable number had stayed for any length of time. Captain Thomas Machin, from the 2nd Artillery, began the construction of an artillery battery, in New Windsor, at the end of 1776, to over-watch the huge cheaveaux de frise spears sunk in the river to obstruct the passage of British ships. The following year, the British Navy worked its way around the incomplete obstacles and then proceeded to burn Kingston. British soldiers stayed long enough in town to ransack several houses.

Amidst the bustle and confusion that always accompanied a major move of the army, Knox was ordered to “ready such [artillery] pieces of your park as are most proper to annoy shipping and cover a body of troops in their passage across a river.” Not content to end the campaign, without attempting one final attack, Washington set his sights on the exposed British positions at Kingsbridge, where a bridge spanned the Spuyten Duyvil, connecting Manhattan with the Bronx. The artillerymen were to “manage the Artillery in the Enemy’s Works”, turning the cannons on their former owners.

King’s Bridge, New York, August 1778. This view looks past the Town, over Harlem Creek, towards the

Hudson River. From Simcoe, A Journal of the Operations of the Queen’s Rangers, (Exeter [1787]) in The

American Revolution in Drawings and Prints A Checklist of 1765 – 1790 Graphics in the Library

of Congress, Donald H. Cresswell, comp., Library of Congress, 1975. The siren call of New

York inexorably beckoned Washington. Having nearly lost more than half of his Army in the defense of

Long Island and subsequently driven out of Manhattan, in 1776, he doggedly pursued its recapture.

King’s Bridge, New York, August 1778. This view looks past the Town, over Harlem Creek, towards the

Hudson River. From Simcoe, A Journal of the Operations of the Queen’s Rangers, (Exeter [1787]) in The

American Revolution in Drawings and Prints A Checklist of 1765 – 1790 Graphics in the Library

of Congress, Donald H. Cresswell, comp., Library of Congress, 1975. The siren call of New

York inexorably beckoned Washington. Having nearly lost more than half of his Army in the defense of

Long Island and subsequently driven out of Manhattan, in 1776, he doggedly pursued its recapture.

Chastellux, visited the camp at Preakness, New Jersey, during preparations for the attack and he remarked that: “the artillery was numerous, and the gunners, in very fine order, were formed in parade, in the foreign manner, that is, each gunner at his battery and ready to fire.” Compromised by the unexpected presence of British vessels in the Hudson River, Washington abruptly called off the attack.

Disappointed, the artillery made the journey north to New Windsor. Lieutenant Colonel Stevens dismissed the levies who had augmented the artillery during the campaign season. Faced with a dearth of volunteers, for the Continental Army, it was common practice to draft soldiers from the state forces, called levies. “Want of cloathing rendered them unfit for duty.” The army also needed to divest itself “of every mouth that” they “could do without.” Had they not adopted this expedient “want of Flour would have disbanded the whole army.” Many of the levies could have been enlisted in the Continental service “for the sake of Cloathes, [and they would] have dispensed with the Money Bounty” for the time being.

Despite the favorable impression made on Chastellux, at Preakness, New Jersey, Knox was not as sanguine about his situation: “The soldier, ragged almost to nakedness, has to sit down at this period, and with an axe - perhaps his only tool, and probably a bad one - to make his habitation for winter. However, this, and being punished with hunger into the bargain, the soldiers and officers have borne with a fortitude almost super-human.”

Not happy with Stevens’ choice for the artillery’s hutting ground, Knox moved it to a woodlot on the southern side of the Clove Road between the fork of two small streams. The artillery park was 1¼ miles due west of General Washington’s headquarters, along the Hudson River, at the house of Thomas Ellison, the father of John Ellison. With their commands exposed to the elements, the officers were ordered to ensure that the soldiers do not burn any wood “that will answer for hutting.”

General Washington’s Headquarters by John Ludlow Morton - The Thomas Ellison House.

Constructed by merchant Thomas Ellison, in New Windsor, on the Hudson River, in the 1720s, this

house served as a headquarters for General Washington. He used it for a short time during the summer of

1779 and again over the winter of 1780-1781. The house was demolished in the nineteenth century.

Knox’s Headquarters State Historic Site, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic

Preservation.

General Washington’s Headquarters by John Ludlow Morton - The Thomas Ellison House.

Constructed by merchant Thomas Ellison, in New Windsor, on the Hudson River, in the 1720s, this

house served as a headquarters for General Washington. He used it for a short time during the summer of

1779 and again over the winter of 1780-1781. The house was demolished in the nineteenth century.

Knox’s Headquarters State Historic Site, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic

Preservation.

The enlisted soldiers’ huts were to be built first and in a uniform fashion. A fatigue party of four men who knew the “mode of getting shingles to be turned” made the materials for the hut roofs. On December 12, Lieutenant William S. Pennington of the 2nd Artillery wrote: “This Day we finish’d Covering two hutts for the men, being only the Sixth Day Since we began them, they are very Convenient with good chimnies and one twenty feet square. The wether being very moderate for the Season of the year help’d to feciliate the Work.”

Soldier huts. The huts at the New Windsor artillery

park were similar to these huts, reproductions

of those built by the Continental Army, in Jockey

Hollow, at Morristown, New Jersey, the year before.

Morristown National Historic Park. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service.

Soldier huts. The huts at the New Windsor artillery

park were similar to these huts, reproductions

of those built by the Continental Army, in Jockey

Hollow, at Morristown, New Jersey, the year before.

Morristown National Historic Park. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service.

The bleak hut interior of a soldier hut. Morristown

National Historic Park. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service

The bleak hut interior of a soldier hut. Morristown

National Historic Park. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service

The officers fixed the dimensions of their huts: “Uniformly of a size: The length 26 & the width 20 feet in the clear.... except the two Hutts on the flanks which are to be two feet longer on account of the Off[ice]rs of two companies living together.” To make the officers stay as comfortable as possible, a sawmill was engaged for the purpose of cutting a “sufficiency of boards.” Besides working in the sawmill, soldiers were also making lime and charcoal. They stayed in tents and probably attached field stone fireplaces and chimneys to them while the work progressed. The wedge shaped common tents, usually occupied by the enlisted soldiers, generally held four to six men, depending on whether they were the smaller English or larger French style. By December 20th, the men had “mostly got into their Huts.”

Lieutenant Pennington did not move into his hut until January 5. Though not yet furnished it was “much comfortabler than [the] linnen walls” of his marquee tent. Lieutenant Colonel Stevens hut was “to have a large hall in it for dancing.” By the following summer, Stevens wrote to Captain Gershom Mott of his regiment: “If you are disposed to come on to this Quarter, I have an Excellent House and Garden at your Service and I’m convinced Mrs. Mott might make herself very comfortable here.” When the camp was later turned into a hospital there was a total of thirty-two artillery huts reported. There were probably originally more, because the huts of the companies that marched to West Point, in the spring, were ordered “immediately torn down and made use of as Firewood.”

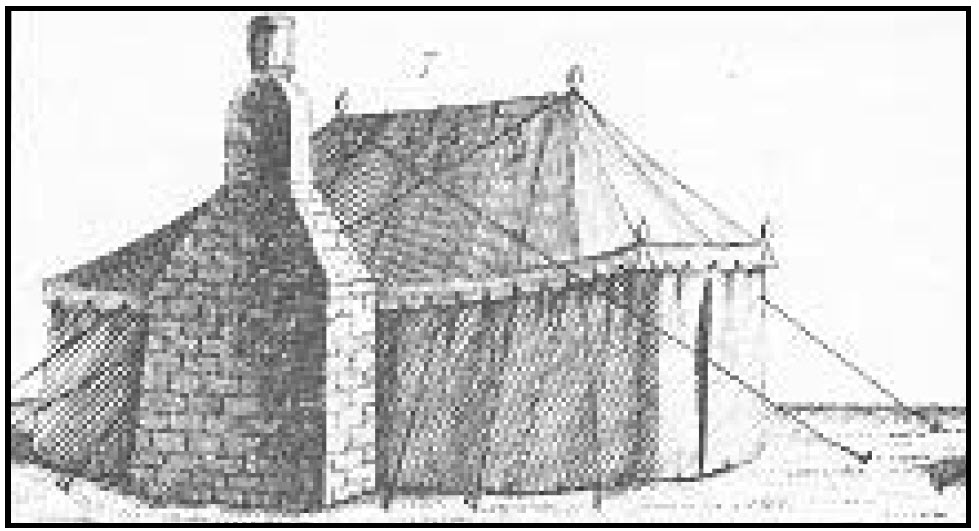

Officer marquee tent with attached fireplace and

chimney. The officers did not move into their huts

until the ones for the enlisted men were finished.

“Modern Tents” Plate 1, Francis Grose Military

Antiquities respecting a History of the

English Army, from Conquest to the Present

Time. 2 vols. (London, 1801).

Officer marquee tent with attached fireplace and

chimney. The officers did not move into their huts

until the ones for the enlisted men were finished.

“Modern Tents” Plate 1, Francis Grose Military

Antiquities respecting a History of the

English Army, from Conquest to the Present

Time. 2 vols. (London, 1801).

Captain William Stevens, late of the 2nd Continental Artillery, published an artillery manual in 1797 in which he described the general formation of an American artillery park during the Revolution:

In the following order, the guns, howitzers, and mortars in the first line, placed thus: two 24 pounders on the right, two twelve pounders on the right, two twelve pounders on the left, and the six pounders next on the right, the three pounders next on the left flank; the mortars in the center, and the howitzers divided equally on the right and left of them; and the rest of the heavy pieces divided next to them, and the flag of the park hoisted in center of the first line; the limbers form a second line, three paces behind their respective pieces; and the ammunition waggons and tumbrels form a third line, ten paces in the rear of their respective pieces. The spare ammunition of the artillery and army, form the next line, at fifteen paces in the rear of each line. The next, the artificers’[skilled tradesman such as carpenters, blacksmiths and wheelwrights] waggons, with their tools, &c. The next line, at fifteen paces, is the baggage waggons of the artillery, artificers, &c. ... The regiments of the artillery encamped about fifty paces in the rear of the park, with their front to the park... The tents of the non-commissioned officers and matrosses were pitched in two ranks, with an interval of six paces between the ranks... The captains and subalterns [lieutenants and ensigns] tents are to be in one line, twenty feet from the the rear of the men’s tents... The field officers are to be in one line, thirty feet from the line of officers.... The kitchens are to be dug behind their respective companies, forty feet from the field officers’s tents. The sutlers’ [licensed civilian vendors] tents are to be behind the kitchens. The commissaries of military stores encamp on the left of the officers, in a line; the artificers encamp on the left of the artillery; the horses belonging to the park are to be placed in a line twenty feet behind the kitchens....

In vivid contrast to the previous winter, when New York Harbor froze over, the weather was remarkably mild. During December, the height of hut building, the only appreciable amount of snow was three or four inches on the 3rd. Several days in the middle of the month, the soldiers enjoyed the “pleasant, remarkable weather for the season – snow all gone.” With few exceptions, this trend would continue throughout the winter. “Considerable rain fell early in the morning” on January 10th which carried off all of the snow. In January, rain fell on nine days, equal to the number in which snow fell. Cold spells lasted only a few days. Dr. Samuel Adams, from the 3rd Artillery, enjoyed a sleigh ride on March 8th, when five inches fell, the last appreciable amount for the season. Snow fell for the last time in early April. The spring weather was fair with the typical mixture of clouds and sun.

At the Morristown, New Jersey encampment the year before, the soldiers struggled against the worst winter of the century. Untaxed by the moderate temperatures of this winter, some of the soldiers devoted their energy to more treacherous pursuits. “Tickets in the 4th class of the United States Lottery” were “to be sold at the pay office in New Windsor”, in December.

In New Jersey, the soldiers of the Pennsylvania Line were soon to play for much higher stakes. On the first of January, emboldened by too much holiday cheer, they mutinied, because of the long standing dispute with authorities, over their pay, clothing, food, the conditions in camp and their terms of service. Over 2,000 strong, Washington hesitated to send the army against them. He let state officials negotiate an end to the crisis.

The events in New Jersey were a stark contrast to the New Year’s celebration, of the officers, at the artillery park. Dr. Adams wrote in his journal: “Dined at General Knox’s [Ellison’s], as did most every officer in the [Artillery] Brigade - excellent dinner, everything conducted with harmony...”

Major General William Heath, commander of West Point, noted in his journal, on January 7, that General Knox had left for the eastern states to “represent the alarming situation and sufferings of the army” to the state legislatures to shame them into providing some measure of relief. Heath himself would be sent on the same fool’s errand in May.

When the much smaller New Jersey Line, encamped at Pompton, New Jersey, followed the lead of the Pennsylvanians, Washington ordered Major General Robert Howe to crush the insurrection. Mutiny was a contagion that must be quickly contained, lest it affect the entire army. The mutineers expected Congress to cave into their demands like it did for the Pennsylvania Line. They were sadly mistaken.

A detachment from the artillery park accompanied Howe. After he quickly put down the uprising and executed two of the ringleaders, Howe waited to see if the British on Staten Island would try to take advantage of the situation. The British made no moves, but the New Hampshire detachment and artillery were retained in the area to prevent further unrest.

Knox prepared detailed lists of supplies for the upcoming campaign:

Artillery Proper for a Siege 6 13 inch mortars 30 24 pounders 20 18 do 20 brass Howitzers 8 inch These may be brafs or iron, there being but little difference in the weight of battering cannon of these calibre if iron the metal ought to be excellent. The above calibers supposed to be English measure.

Most of the guns, at West Point, could not be included in the estimate, if the campaign was switched from New York to the lesser objectives of “Charleston, [South Carolina], Savanna[h, Georgia] [or] Penobscot [Maine].”

In February, Knox refined the composition of the siege batteries and identified specifically where they were to be placed around New York. After identifying the requirements, Knox listed the whereabouts of the known siege guns and whether the states or the continent owned them.

Additional artillerymen headed the long list of deficiencies as “the regiments of Artillery are extremely reduced.” The regiments were only manned at about half of their authorized strength. When the states did forward new recruits, few of them were able to perform the duties of a soldier. “Boys of a yard and a half long [were] paraded for muster, absolutely incapable of sustaining the weight of a soldier’s accoutrements.” Many were sent back, but necessity forced the retention, of some, of the unqualified recruits, who “yet may in a campaign or two be in some degree serviceable.”

The enlistment, of foreign deserters, was forbidden, because in the event of amnesty being offered by their old units, they might return and possibly take others with them. 2nd Artillery recruiting officer Captain Thomas Machin had secured fifty recruits, in the spring, who were enticed to join because of the substantial cash bounty being offered, but he could not obtain clothing for them. There was neither “blue nor Scarlet Cloth nor trimmings” which the clothing purveyor would “be obliged to get from Philadelphia.”

The soldiers were subsisting for “some time on a scant allowance of bread, ... [and with] no fresh meat upon hand ...” [they were] “fed upon what little corned and salted meat... [that had been] laid up for spring use.” A guard had to be placed on the oxen in camp that were being used to move the guns and wagons, not only to prevent them from wandering off, but also to keep them from being eaten. When there was a pressing need for supplies, the quartermasters worked closely with local officials. The usual expedient, to make up shortfalls in the commissariat, was to levy supplies on the farmers in the region. Even though the demands were apportioned by the local magistrates and sheriffs according to the owner’s ability to sustain the loss and that redeemable commissary certificates were given as receipts, there were limits to how much could be seized from the populace. “Coertion both legislative and military have been so frequently employed, that the people have not only lost all confidence in public credit, but are extremely impatient under any exertions of authority to force their property from them.” No where was this more evident than in New York, where the discontent was “serious and embarrassing”. By the middle of April, the flour available in New York and New Jersey would not carry the Army “beyond the beginning of the next month.”

Switching to a quota system, in February 1780, Congress divided the army’s requirements for beef, pork, flour, rum, salt and other necessities among the states. The states, considerably backward in meeting the quotas, pled poverty. There was no lack of resources in the country, but the states lacked the cash for purchase. In the fall of 1779, when the amount reached 200 million dollars, Congress stopped printing money, but that still left huge numbers of depreciated notes in circulation. Though indispensable in financing the war, American paper currency had become synonymous with worthlessness, giving rise to the phrase “not worth a Continental.”

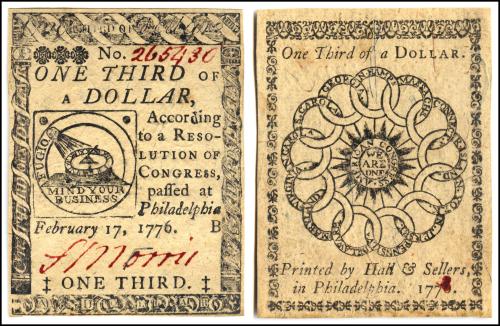

Continental Currency – In the fall of 1779, when the amount reached 200 million dollars, Congress

stopped the presses. It depreciated the old currency and approved a new emission of paper with strict controls

over the amount in circulation.

Continental Currency – In the fall of 1779, when the amount reached 200 million dollars, Congress

stopped the presses. It depreciated the old currency and approved a new emission of paper with strict controls

over the amount in circulation.

To exact some control, Congress created a new emission of currency with a limit of 10 million dollars. An ambitious program was started, in March 1780, to redeem the old currency for new notes at 40/1, thereby reducing the national debt from 200 million to 5 million dollars. After deducting the five million dollar debt remaining from the currency depreciation, Congress would still have another five million available for additional expenditures.

The old currency was supposed to be taxed out of circulation, by the states, and then turned in to Continental officials. The states would receive one dollar, of the new currency, for every 40 dollars of the old. Many Americans, especially in the most active war zones, held Army quartermaster and commissary certificates and paid their taxes with them instead. Often given out for goods seized at the exigencies of the moment, there were countless numbers of these certificates and no reliable estimate of the amounts expended. Consequently, the states had few old bills in their coffers to exchange for the new ones, so they lacked the funds to purchase the supplies levied by Congress.

Rivington’s Gazette, published in British occupied New York City, lampooned the demise of the Continental currency. “The Congress is finally bankrupt! Last Saturday (May 7, 1781) a large body of the inhabitants with paper dollars in their hats by way of cockades, paraded the streets of Philadelphia, carrying colors flying, with a DOG TARRED, and instead of the usual appendage and ornament of feathers, his back was covered with the Congress’ paper dollars.”

With their financial scheme undone by their failure to comprehend the extent to which certificates had been used, Congress muddled through with foreign loans, by wresting what it could from the states, by increasing the number of contracts with private firms and by authorizing their agents to impress any deficiency. When supplies were obtained, lack of transportation and improper storage resulted in considerable wastage. “In the article of flour particularly, which is most subject to waste, the fault in a great measure originates with the Miller who is shamefully careless of the make and security of the Casks.”

Inevitably, there were also cases of fraud. The “United States are charged with much larger quantitys than have been actually supplied, whereby an unrightious advantage has been obtained by individuals to the injury of the Publick.” Not every misrepresentation of the amount of goods supplied was done with criminal intent. When impressment was necessary, some agents, ashamed by the necessity of forcing people, overstated what was delivered to give the owners a better chance of recovering something for their loss and to lessen the amount subject to seizure in the future.

Congress exhorted the states from Pennsylvania north to New Hampshire to remit their share of the $879,342, comprising six months pay for the army. While Congress waited to see how far the states would comply, if at all, Dr. Adams bitterly complained that the condition of the army was that of: “poor miserable dogs without a single shilling in our pockets.”

In addition to pay, officers and soldiers were supposed to receive monetary notes to compensate for depreciation, but like the pay, the depreciation certificates were normally late. Despite the magic worked by the new Superintendent of Finance, Philadelphia merchant Robert Morris, army supply and pay would continue precarious throughout the remainder of the war.

The clothing situation was not any better. Lieutenant Colonel Stevens “procured cloth sufficient to make the Coats for the [2nd Artillery] Regiment, it is not of so fine as quality he cou’d wish, however it will answer the Purpose.” Though regimental tailors were making up the men’s coats, Captain Doughty of the 2nd Artillery wrote to Governor George Clinton of the “great want of every article of Cloathing.” Despite this, soldiers had to be warned about selling their newly issued clothing. The soldiers, in the 2nd, were threatened with severe punishment, if they were base enough to sell the “Regimental Buckles lately issued.”

Old tents were made into covers for the tin camp kettles, because when they were carried the soot stained the uniforms. The clothing situation was so galling to General Washington because:

Ten thousand compleat suits [were] ready in France, and [were] laying there because our public Agents cannot agree whose business it is to ship them; [a quantity has also lain in the West Indies for more than Eighteen Months owing probably to some such cause.] ....There is Cloathing enough lately arrived in private Bottoms to supply the Army. This, my dear Sir [Major General Benjamin Lincoln], is only tantalizing the naked; such is the miserable state of continental Credit, that we cannot command a yard of it; some of the States may, and I hope will, derive an advantage from it, [ in which case I hope they will attend to the colors proper for their Uniforms.] I informed them all, very lately, to what miserable condition their troops would be reduced, except they would lay themselves out for Cloathing.

A deserter notice placed in The New York Packet gives some details on the style of artillery uniforms at this time:

Four Thousand Dollars Reward Deserted from Captain Nath. Donnell’s company third regiment of artillery, commanded by Col. John Crane, When on command at Dobb’s Ferry, John Jacob Moder, gunner, 23 years of age, five feet eight inches high, born in Germany, brown complexion, brown hair, blue eyes, had on a short blue coat, red cuffs and cape, pewter buttons took with him a new red watch-coat, Whoever will secure the above deserter, and bring him to his company, shall receive the above reward. NATH. DONNELL Capt, 3rd regt. artil, West-Point, May 11 [1781]

Officers were expected to maintain the semblance of being gentlemen. The following kit was recommended to a young officer joining the 2nd Continental Artillery, in 1781:

Clothing &c., necessary for a young campaigner: - Beaver hat, .... 15 Coat, faced and lined with scarlet, – white vest and breeches, – plain yellow buttons, – (super-fine [*defined in notes] will be cheapest), .... 60 3 white linen vests and breeches, .... 25 6 ruffled shirts and stocks, .... 60 4 pairs white cotton or linen hose, .... 10 Boots, .... 10 Sword, .... 20 ———— Silver dollars, .... 200

Drawing by French officer Antoine de Verger

showing American soldiers around 1781, including

an artilleryman on the extreme right, who holds a

lint-stock with burning match, ready to fire a piece

of artillery. Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection,

Brown University Library.

Drawing by French officer Antoine de Verger

showing American soldiers around 1781, including

an artilleryman on the extreme right, who holds a

lint-stock with burning match, ready to fire a piece

of artillery. Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection,

Brown University Library.

Lieutenant Colonel Stevens wrote to Captain Gershom Mott of his regiment:

I send you also by the Bearer Serjt Reins, one Hat, one pair of Boots, one pr of Shoes, two pair of Hose, three Yards of Dowlass, three Yards of Rateen, four Shirts, two Black Stocks, one pair of Drilling Breeches and two and a half Yards of Blue Cloth – the whole are of a very course Quality, but I assure you, they are the Best the Store afforded, and I thought tho course, they wou’d be acceptable to you.

Mott’s coat would be considerably more modest than those heretofore worn by the artillery officers. The Continental Congress, angered by the extravagance and waste in procuring the elegant trappings desired by many army officers, finally forbade their use altogether, in February 1781. Unless approved by Congress or Washington, officers were not to “imitate the Enemy in any respect…, especially to wear the uniform of the Enemy’s army or navy” or “wear on his cloaths any gold or silver lace embroidery or vellum, on pain of being cashiered”.

This resolve could have been intended to specifically admonish the artillery officers whose fancy uniforms differed little from their British counterparts. The resolves were to take effect the following year.

The following rebuke given to Major Sebastian Bauman, from the 2nd Artillery, seems to suggest that they were allowed to retain their gold lace. Bauman complained to General Knox, in August, that he was reprimanded for not having a “gilded coat, agreeable to the Established Custom of the Regiment.”

Some thick woolen watch coats were available for soldiers doing extended duty outdoors to prevent the debilitating effects of cold weather illnesses and injuries. They were however, more inured to the rigors of service than their counterparts from earlier in the war.

There were no deaths in this camp of mostly veteran soldiers. The weak had long since died or quit the field. There were the usual maladies to keep doctors like Samuel Adams busy. He inoculated soldiers as well as civilians for the highly contagious and deadly small pox.

Colonel Stevens’ children were among those inoculated. Anyone living in proximity to the army encampments needed to go through the painful process. The serum was introduced into the body by a quill through a scratch or puncture. Though the patients became quite ill, the overwhelming majority recovered and wore the scars left behind by the vesicles for life.

Made from early stage smallpox vesicles, the serum was probably obtained from local physician Moses Higby, who was lodging at Squire Belknaps, just north of the artillery park. In 1777, Higby administered the emetic which forced out the musketball swallowed by a British spy who was captured in New Windsor. Inside the musketball there was a message to General Burgoyne, at Saratoga, that the British army from New York City was making a diversion in his favor along the Hudson River.

(To be continued)

Next Issue of Journal!

The Next Issue of the OCHS Journal is now accepting articles for consideration.

Authors

More guidelines for authors

Classics from the Journal

NEW!! The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part I

by Michael S. McGurty

NEW!! The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part II

by Michael S. McGurty

NEW!! Orange County Militia During the American Revolutionary War

by Alan Aimone

George Washington's Masonic Activities in Orange County

by Andrew J. Zarutskie

Prisoners of War in Goshen

by Harold J. Jonas

John Robinson of Newburgh

by Margaret V. S. Wallace

The Battle of Fort Montgomery

by Donald F. Clark

Role of Regional Revolutionary Women

by Michelle P. Figliomeni

Robert R. Burnet (1762-1854)- The Last Continental Officer

by Alan C. Aimone and Barbara A. Aimone

The Revolutionary Soldier in Washington's Army

by Edward C. Cass

Technical Communication in the Amercan Revolution

by Carol Siri Johnson

New Windsor Cantonment

by E. Jane Townsend

Sidman's Bridge

by Kenneth R. Rose

Corridor Through the Mountains

by Richard Koke

Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck and "The Sybil"

by Amy Kesselman

The Store at Coldengham (1767-1768)

by Jay A. Campbell