NEW WINDSOR CANTONMENT AND THE TOWN OF NEW WINDSOR

Two Communities Co-Exist in 1782-1783

E. Jane Townsend

[Editor's Note: This article appeared in the 1996 Issue of the Journal of the Orange County Historical Society. It is being republished on the website as part of the ongoing activities surrounding the 250th Anniversary of the Revolutionary War. The footnoted version is contained in the 1996 Journal which is available for purchase. JAC]

Introduction

"We are busily completing our Town. It will I suppose contain of Honest men - women...and the progeny of both, ten thousands soulds."

So Tench Tilghman, aide-de-camp to George Washington, described the Army's cantonment that was taking shape behind Snake Hill in the Town of New Windsor in the fall of 1782.

Today, New Windsor cantonment is popularly known as the final encampment of Washington's army. It was here that Washington issued his ceasefire orders, effective April 19, 1783, to bring the eight-year-long war to an end. And above all, the Cantonment is remembered as the site of Washington's March 15th, 1783 meeting with his officers and the Newburgh Addresses.

While Tench Tilghman called the Cantonment a town, the Marquis de Chastellux, on his visit in early December, marveled at this community of log barracks he saw being constructed in regular rows on the hillsides. Here at New Windsor, 7,000 soldiers, together with some 500 women and children - camp followers - established a winter cantonment that would be known as the best throughout the war.

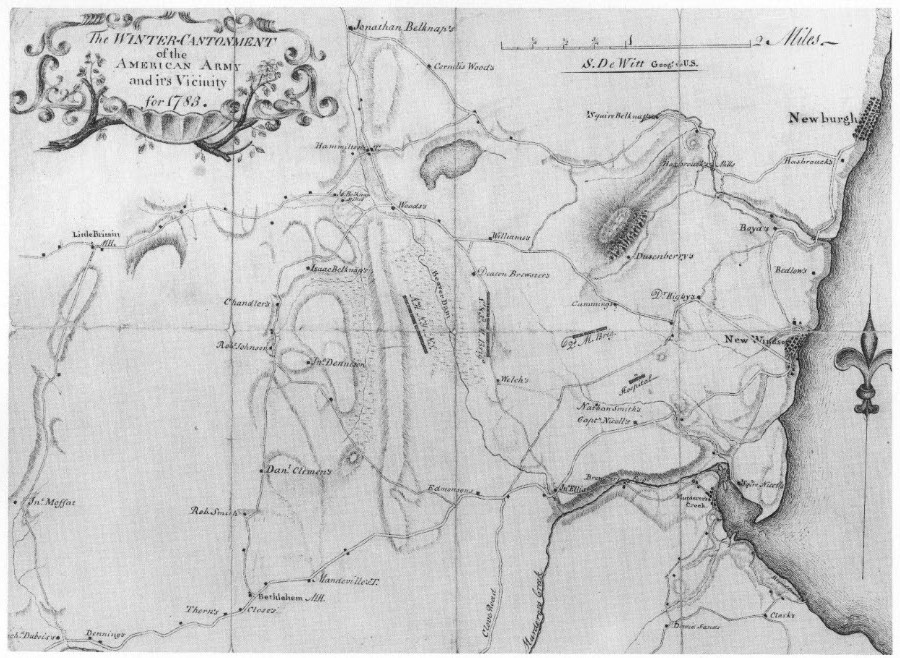

The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity for 1783, S. DeWitt, See digital collections of the NYHS. www.bit.ly/dewitt-map

The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and its Vicinity for 1783, S. DeWitt, See digital collections of the NYHS. www.bit.ly/dewitt-map

Valley Forge and Morristown served as encampments over the winter months of 1777-78 and 1779-80 respectively until the campaign season began again in the spring. At New Windsor, the Cantonment lasted almost a full eight months, from October, 1782 to late June, 1783 when the last troops were furloughed home.

For the 1130 people living in New Windsor, the new Windsor Cantonment was the community's last and most significant contact with the continental Army. Almost from the very beginning of the war, Army units or personnel encamped in New Windsor or marched through. The climax came with the establishment of this large and long-lived Cantonment behind Snake Hill in 1782.

This paper will address the question of how the two communities - the people of New Windsor Cantonment and of the Town of New Windsor interacted socially and economically; in effect, how they co-existed.

Ostensibly, New Windsor Cantonment and the Town of New Windsor were two separate and disparate communities. In fact, there were many points of contact. Beyond the army's utilization of physical resources - land for hutting, woodlots providing logs for building the huts and firewood for heating them, meadows for forage and pasture for the Army's horses and private homes for housing officers - there was a full range of exchange of goods and services and of social amenities between them.

Social and economic contact between the two is seen especially among the high-ranking officers who billeted in homes of the more affluent residents. Junior officers dealt with their civilian counterparts and the trades people of the New Windsor and Newburgh area. Enlisted men's activities in the community were minimal and generally extra-legal.

The daily life of junior officers and their activities is illustrated by the daybook of Lt. Benjamin Gilbert. A preliminary study of merchant/miller John Ellison and his brother, shopkeeper William Ellison shows how their economic and business interests were affected by the war. In this paper, both Lt. Gilbert and the Ellisons are examples of the interaction between the two communities, the cantonment and the Town of New Windsor.

The Physical Setting

New Windsor, on the Hudson River, is just north of the Hudson Highlands that were so strategically important throughout the Revolutionary War. West Point, ten miles south, became the principal fort on the river in 1778, and 50 miles further south, New York City remained under British occupation.

One of the principal documents for the study of the New Windsor Cantonment is the map of the Cantonment drawn by Geographer to the Continental Army, Simeon DeWitt. "The Winter Cantonment of the American Army and it's [sic] Vicinity in 1783" locates this military enclave of nearly 600 huts, encompassing some 1600 acres of woodlots and meadow land, three miles from the main village of New Windsor on the waterfront. The three principal encampment areas are denoted: the New York, New Hampshire, New Jersey and Maryland troops encamped on rising ground to the west of Beaver Dam (also known as Silver Stream); the 1st and 3rd Massachusetts Brigades east of the stream; and the 2nd Massachusetts Brigade en- camped further east opposite the Army's hospital.

Roads going north to Newburgh, west to Little Britain and Goshen, and south through the Highlands linked the Cantonment with the community of New Windsor. While the town's center was on the waterfront, there were houses, taverns, and churches along the roads and at crossroads radiating out from the village

Thirty-five structures on the DeWitt map, each indicated by a small square and each identified with the owner's name, have proved to be significant to the Army in some way, as quarters for officers, as taverns that the Army frequented or simply as homes of the more prominent inhabitants, many of whom supplied wood, straw or foodstuffs to the Army.

Housing for officers, for example, was provided by William Edmonston for Major General Arthur St. Clair, head of the New York, New Jersey, New Hampshire and Maryland lines; by Deacon Samuel Brewster for Major General Robert Howe, head of the Massachusetts brigades; by merchant/miller John Ellison for Major General Horatio Gates, Commandant of the Cantonment. Squire Abel Belknap's in Newburgh was used by Major General William Heath on first arriving in New Windsor and used again on his return from his leave in Massachusetts when he succeeded Gates who left in the spring. Dusenbury's was used for some of the medical personnel earlier in the war, and, also earlier, Squire John Nicoll's housed Dr. John Cochran, Director General of the Medical Department.

In Newburgh, Commander-in-Chief George Washington and his military family used Jonathan Hasbrouck's from April, 1782 until August, 1783, except for a three month period in 1782 when he was encamped with the army at Verplanck's Point, near Peekskill.

As for some other houses, Robert Boyd, Jr.'s is identified as well as Dr. Moses Higby's. Boyd, an important blacksmith and a member of New Windsor's Committee of Safety, supplied muskets to New York's provincial congress in 1775 and furnished supplies for the Army's smith shop at the Cantonment and for the West Point garrison in 1783. Doctor Higby is now remembered for his role in apprehending a British spy after the fall of Forts Montgomery and Clinton. He administered an emetic to the suspect that yielded up a silver bullet containing a secret message intended for General Burgoyne. Two taverns near the Cantonment, Mandevilles and Hamiltons, are also on the DeWitt map, identified with a "T" following their names.

The Cantonment Begins: Order is Established

"It is with sensible pain the General finds the country covered, and the Farm houses, crowded with soldiers who are committing wanton instances of plunder and outrage, to the great inconvenience and injury of the Inhabitants ... "

–- G .Washington,General Orders, October 30, 1782

Soon after his troops made the 2 1/2 day march from Verplanck's Point, in late October, 1782, General Heath reported to Washington that it was done "in the best order and with great regularity." With the arrival of the right wing, led by General Gates, their immediate task lay before them: to establish the Army settlement of huts before the approach of winter and to ensure order and discipline within the Cantonment and its immediate environs.

Quartermaster General Colonel Timothy Pickering issued the hutting orders. By Christmas, the huts were completed and satisfied everyone's expectations. Washington was pleased by the "present comfortable and beautifull (sic) situation of the troops..." Food rations, now provided under contract, were regular, if not gustatory fare. Markets were established so the local townspeople could come into the Cantonment to sell provisions. George Washington took satisfaction in knowing the troops were better fed, housed and clothed than ever before.

An additional concern was the need to maintain Army discipline. Throughout the war, Washington tried to ensure that the Army would not be a scourge on its own people. Without "Order, Regularity and Discipline," an army "is no better than a Commissioned Mob," Washington wrote in 1776, soon after assuming command of the Continental Army at Cambridge, Massachusetts when the army seemed to him more like a rabble in arms.

In the 1777 campaign season, incidents of the Army's plundering local inhabitants on the pretext they were Tories were strongly condemned by Washington as "a disgrace to all Armies, much more to one which is raised for the express purpose of preserving American liberty and property." And in 1778, for example, he had hoped the Army would be as little "burthensome" as possible. Now four years later as the Army was establishing its winter cantonment at New Windsor, Washington once again confronted his army's looting and pillaging. From his nearby headquarters in Newburgh, Washington dealt summarily with the Army's excesses in three general orders from October 30 to November 19, 1782.

In the first, finding the "country covered, and the Farm houses crowded with soldiers committing wanton instances of plunder and outrage", Washington forbade these "unsoldierly practices" and called upon officers to put a stop to them by "prompt and exemplary punishment to be inflicted on the Guilty." Two weeks later, Washington issued stronger orders to deal with "the enormities which have been committed... are scandalous beyond description and a disgrace to any army. .. " Allowing soldiers to "ramble" about the country had to stop, the issuing of passes would be restricted, and no soldier was to be away from the camp after the beating of retreat.

Furthermore, rolls were to be called at irregular hours during the night. These orders were to be read at three successive evening roll calls so that every soldier would be aware of them and could not plead ignorance. He ordered General Gates, general officers and commanding officers of brigades to meet at Gates' headquarters the next day to review the situation in the camp and establish picquets and guards and order patrols to sufficiently control the troops within "proper bounds."

November 19, in his third general orders, Washington wrote again of "marauding" troops that so "scandalously prevailed." Spot roll calls he had ordered October 30 were now to be called at any time but at least four times in every twenty-four hours. Should any commanding officer of a regiment suspect his soldiers absent at night "marauding" he was to issue a catchroll turning all the men out on the parade. Those absent were to be punished at the troop beating.

Furthermore, passes allowing noncommissioned officers and soldiers to go beyond the limits of the camp would be issued solely by generals and officers commanding the respective regiments. Finally, a patrol was to be formed to apprehend those without passes and to administer punishments of up to 100 lashes on the spot. Any soldiers found with goods taken from local inhabitants were to be tried for their lives by a General Courtsmartial.

An examination of courtsmartials compiled from three orderly books of regiments at the Cantonment and from Washington's general orders suggests that the most frequent crimes were desertion and theft. These were followed by assault and abuse, absence without leave and absence from roll call, mutinous behavior, disobedience of orders, neglect of duty, attempted murder, drunkenness, fraud, overstaying furloughs, vandalism and mischievous conduct, plundering citizens, and disorderly conduct.

When the soldiers were brought up on charges involving the local inhabitants, these were incidents of stealing and disorderly conduct. For example, in November, two soldiers of the 1st New York Regiment were convicted of leaving camp and killing an ox belonging to a civilian, and were sentenced to 100 lashes each.

In late January, at a courtsmartial, Robert Chase and Willam Waddle of the 1st New York Regiment were convicted of plundering an inhabitant and sentenced to receive 100 lashes each and to have half their pay stopped until the amount of five dollars was reached. Two days later another courtsmartial found ten soldiers of the Light Infantry Company of the 1st Massachusetts accused of killing a cow, stealing fowls and 11 geese. They were found guilty only of stealing the geese. Three were to receive 100 lashes each, the others 75 lashes. All had their pay stopped until the amount of $15 could be paid to Jonas Williams, owner of the geese.

In early spring, Michael Smith, Jonas Newell, John Blake, and Nathan Curtis of the 1st Massachusetts Regiment were charged with breaking open the house of James Munnell, insulting and abusing the occupants, attempting to kill Captains James Frye and Benjamin Ellis and robbing them of a hat. The soldiers were acquitted of all charges.

Once the blatant "marauding" ended, the camp fell into a routine in which further incidences occurred sporadically. For the most part, the Army remained in its enclave, regulated by police units within the Cantonment and regular patrols outside it. But here, too, fine tuning was necessary.

In early December, it was decided that army patrols could no longer stop at any houses unless a search for deserters was being made and if so, it was to be done under the direction of commissioned or non-commissioned officers. This would prevent patrols from committing "irregularities" when they entered civilians' houses.

In January, enterprising soldiers were found to be cutting and selling wood to the townspeople in New Windsor. Washington ordered the practice stopped. Another soldier was courtmartialed on charges he had taken an Army axe into the countryside to sell. He was acquitted. In a letter to Governor Clinton in February, Washington reported how he had "taken much pains to prevent the violation of private property by the Troops." He also sought Clinton's help in having the New York legislature prohibit civilian purchases of public property, ie. Army goods, with violations punishable by fine.

While it was desirable to have the army physically isolated from the main village of New Windsor, civilians did provide services to the Cantonment. Tailors and seamstresses were welcomed into the Cantonment to sew. Country people were encouraged to sell fresh provisions - vegetables and roots - to supplement the daily ration provided under the contract. When reports of them being "maltreated and plundered" reached Washington, he reacted. Such behavior was "not only scandalous, in itself but injurious to the Army as well as the Inhabitants."

Consequently, market areas were designated in certain locales and guards assigned for protection. Any soldier who abused or defrauded the vendors or attempted to purchase goods before they arrived at the designated area would be punished. Two days after this order, a Corporal McLean went before a regimental courtsmartial charged with "suffering a Markett man to be plundered in his presence." Found guilty, he was reduced to a private.

The New York Packet in February carried the Quartermaster General's announcement of three market areas at the Cantonment, one each for the three main lines of troops, and advised that market people would be able to come into camp without interruption and that an officer with a guard was to attend each marketplace daily. Later the three were reduced to two and held on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

In the spring, Washington ordered that regimental gardens be planted, believing they would contribute to the soldiers' health as well as provide amusement. Trusty soldiers were given passes to go into the country to collect seeds. The Quartermaster General's office also advertised for people to bring in garden seeds to his office for distribution to the soldiers.

Sutlers, that is merchants, selling goods to the soldiers were another group of civilians with access to the Cantonment. Not long after the troops arrived at New Windsor, Washington learned that some sutlers banned from West Point because of improper conduct were coming to New Windsor and building huts. For better control, Washington asked General Gates, in consultation with the commanding officers of the brigades, to decide on the names and numbers of sutlers. Licenses would then be issued by the Quartermaster General's department. Any sutler selling liquor to the soldiers without a license would have it seized and confiscated, and his hut, if built, "pulled down." The officers responded promptly, submitting their recommendations to Gates. Brigadier General John Patterson, head of the 1st Massachusetts Brigade, recommended a sutler who had been with the brigade several years, had "behaved well," and was owed money by the Army. Colonel Henry Dearborn of the First New Hampshire Regiment recommended a Ruben Daley as a sutler.

Francis Lusk, from the community of Little Britain on the road to Goshen petitioned to be approved as a sutler to the Jersey line, stating he had "a considerable quantity of butter, cheese, and good liquors." He also intended to keep for sale a large quantity of vegetables. (Lusk later purchased twelve ox yokes and two lots of harness at the Army's public auction of goods in September, 1783.)

Another merchant was Nathaniel Sackett from Fishkill who obtained Washington's permission to "suttle" to the Army in the spring of 1782. Sackett received a note of thanks by Washington's staff for the cheese he sent Washington in the fall.

Subsequently, general orders, issued in March, 1783, tightened regulations. Only one sutler would be allowed per brigade; the quality and prices of the sutler's stores were to be examined weekly or more often to correct any abuses; no mixed liquors could be sold; and sutlers not licensed would have to leave within twenty days. Individual regiments imposed further restrictions on the selling of liquor.

In March, the 2nd Massachusetts banned anyone in the regiment from selling cider, it "proving injurious." In April (1783) sutlers for the 1st New York Regiment were forbidden to sell soldiers liquor in quantities that would intoxicate them and, if they did, they would be "turned off the Ground."

This last was perhaps in reaction both to the Washington's General Orders of March 3 respecting the sutlers and what only can be described as general delirium that erupted in camp in late March to the unofficial news that a peace treaty had been agreed to. The soldiers had cause to celebrate, and celebrate they did. They "caroused" all night and the next day continued "marching, huzzaing (sic) and drinking all day," according to the diary account of junior officer Benjamin Gilbert.

The Community of New Windsor and Newburgh from a junior officer's perspective - Lt. Benjamin Gilbert

“The 22d Thursday. Afternoon Doctor Finlay. - Lawton, Ens. Wing & I went to N Windsor, where we drank wine & punch in plenty."

-- Daybook, B. Gilbert, May 22, 1783

Throughout the winter, rumors of a coming peace treaty circulated; it was becoming increasingly unlikely that there would be another campaign season in the spring. From his headquarters at Hasbrouck's, Washington wrote to General Heath on leave in Massachusetts that he was "without amusements or avocations . . . spending another Winter . . amongst these rugged and dreary Mountains." Nevertheless, to keep the Army well trained and its spirit high, he hoped to "turn their duty into an Amusement, by awakening again the spirit of Emulation and love of Military Parade and glory, which was so conspicuous the last Campaign."

Many officers, within the numbers allowed, opted for furloughs, staying away from camp as long as permitted. One who stayed was Lieutenant Benjamin Gilbert (1755-1829) of the 5th Massachusetts whose daybook and letters chronicle his activities during this period.

Gilbert arrived at the Cantonment in early December in time to help put lathing to his hut, after serving on the lines with the light infantry of the 5th Massachussetts Regiment. Subsequently, he transferred to a regular infantry company within his regiment. Gilbert complained of the tedium of the winter camp. In the spring of 1783, when the provisional peace treaty and Washington's ceasefire orders were announced, it was not known when or who would be furloughed or discharged. Gilbert wrote to his father, "... time never passed more disagreable than it does at present" and to his brother-in-law, "I spend my time in idleness under a continual agjutation (sic) of mind, praying for a speedy desolution of the Army."

Activities, official and unofficial, were found to while away the winter hours in and out of camp. A fox hunt was promoted in early December. Promising "plenty of game", "pleasant" sport, and "elegant entertainment", officers and inhabitants of Orange and Ulster counties were invited to rendezvous at Woods for the hunt on December 23. Woods, a popular tavern, was located just north of the Cantonment.

Despite personal concerns, Gilbert also managed to have some good times in camp "moving" country dances and taking grog in fellow officers' huts ("drinking Saturday night's health," occasionally drinking too freely, and on occasion having to be "hung out on the line to dry.")

After arriving at the Cantonment, Gilbert helped a newly commissioned lieutenant "wet his commission" in late December and drank grog with a friend who was resigning his in early January. In January, too, he began to explore more fully the New Windsor and Newburgh communities. He went for a "high caper" or a "civil" dance, ate and drank at local taverns, visited with some of the local townspeople, and had an occasional shopping excursion. He attended a "civil dance" with three other junior officers at a Captain Colman's in Newburgh (which left him with a severe headache the following day) and was at another home in Newburgh "acting the part of proper Helions all night" before returning to camp early the following morning. He also attended a meeting in New Wmdsor one Sunday in early February and on his way back, it being "severely cold,"called at Dr. Higbies ... to warm …”

Two social visits were also paid on him at camp in winter. A Mr. Merritt from Collaburgh, present day Croton Landing, whom he knew when he was stationed at Soldier's Fortune in 1779, visited him at the Cantonment. And he met the Holme's (or Homes?) family when Mr. Holmes and his family, including three daughters, came into camp to sew and stayed to drink tea and "move a number of country dances" in his hut. He saw the Holmes' two more times, the first within a few days of their visit to the Cantonment.

Gilbert, accompanied by two friends, visited them and spent the night "very agreably," getting back to camp before roll call. A week later, he was again at Holmes', met with a kind reception and arrived back early in the morning to his hut. This is the last time his daybook mentioned the Holmes, for he had discovered Wyoma's, a brothel somewhere in the vicinity of Newburgh, and he began to have "enjoyable" times there. Soon he and one or two of his friends established a routine, going to Wyoma's for a night's recreation and returning to camp in the early morning hours in time for the morning roll call and resumption of duties.

From this point on, Gilbert's social life, except for two parties at a townperson's -- one described as a genteel dance with the ladies of that place, was Wyoma's. His daybook places him there 15 times in April and May; about twice a week. He last mentioned Wyoma's on June 20. He "drank tea with the Girls and staid all night."

On June 23, Gilbert, now a member of the reorganized 3rd Massachusetts, was ordered to West Point.

Establishments such as Wyoma's and local taverns thrived during the time the Army was at New Windsor. Gilbert enjoyed cake and methiglon (a spiced mead drink) at Van Deursen's, a "house of entertainment" at the Sign of the Confederation in New Windsor opened eight months earlier. He promised good accommodations for man and horse and had a variety of entertainments, including cricket, chess, 9-pin alley and bindy wicket.

Sarah Hamilton's tavern (located on the DeWitt map), was "the scene of more army life of a given character than any of the numerous hostelries of the town .... " according to E.M. Ruttenber. Army personnel took advantage of the food, drink, and sociability that taverns provided, occasionally to excess.

At Smith's tavern a fight occurred in March, 1783 between Sergeant Niles and Isaac Reed of the 8th Massachusetts Regiment, both of whom were courtmartialed and subsequently found guilty of being out of camp without leave and behaving in a "riotous manner."

Shops and stores also did a good business with Army personnel. One shopkeeper, John Currie, advertised in The New York Packet of having received a large and elegant assortment of dry goods and stationery goods suitable for both army and country for sale at the house of Mr. William Ellison in New Windsor. Currie would dispose of these "at the lowest price for cash, bank notes, honourable Robert Morris' Notes, Contractors due Bills, Subsistance notes or any kind of country produce."

Lt. Benjamin Gilbert patronized Currie's shop. On February 1, accompanied by two fellow junior officers, Gilbert went to New Windsor and bought of Mr. Curry (sic) a piece of Britannia for 4 1/3 dollars and a pen knife for 3 dollars. Currie advertised in the Packet that among the stationery goods were penknives and razors "of all sorts." Gilbert's diary recorded only this one shopping trip to Currie's.

In late June, he was en route to West Point and to an eventual discharge. Gilbert's path crossed with the Ellisons only that one day when he shopped at John Currie's store at the William Ellison house.

In their Midst: The Army from the Inhabitants' Perspective --John and William Ellison of New Windsor

“I have a very good bedchamber in a warm Stone House where you would not be so uncomfortable as you were in old Yorke. The rest of my Quarters are tolerable and Dining room better than at York …”

-- Gates to his wife, Jan.17, 1783 from John Ellison's house

Like others in the Hudson Valley whose livelihood depended upon commercial and mercantile ties to New York City, John (1736-1814) and William Ellison (1739-1810) of New Windsor had to adapt to the changes war brought. For nearly 35 years, Ellison family sloops had plied the Hudson, carrying wheat and flour, the latter ground at John Ellison's mill, to their family dock in New York City for city and overseas markets, and then returned bringing goods for sale at William Ellison's New Windsor store. The war years in effect ended what had been a lucrative interlocking family enterprise.

The Ellison family's rise to prominence that made it one of the most influential and prosperous families of Ulster/Orange County in the 18th century and early 19th centuries had its beginnings with John Ellison I (d. 1724) who emigrated to America in 1688. He was a carpenter and did well, eventually owning a wharf on the west side in today's Whitehall section of lower Manhattan, and he invested in other real estate in and outside the city in the precinct of the Highlands.

In 1723, his son, Thomas Ellison, Sr. (1701-1779), then 22 years old, moved from New York to New Windsor and built a house, wharf and warehouse on the Hudson River on lands his father purchased for him. In 1739, Thomas, Sr. purchased land on Silver Stream, not far from the river and, two years later, built a grist mill. From this a successful milling business and carrying trade developed that ultimately extended beyond New Windsor and New York City to England, Spain, and the West Indies.

In 1754 Thomas Ellison, Sr. contracted for a stone house to be built near his mill on Silver Stream. His son John and John's wife Catherine moved into the stately Georgian-style house in about 1760. While John managed the mill, his brother William kept the store and ran the sloops while the third Ellison brother, Thomas, Jr., served as the family's agent in New York City. His letters, for most of the 1760s up to the war, kept his father and brothers in New Windsor informed of commodity prices, especially wheat and flour, whether or not prices were "dull" or "quick," and would they hold, rise or decline.

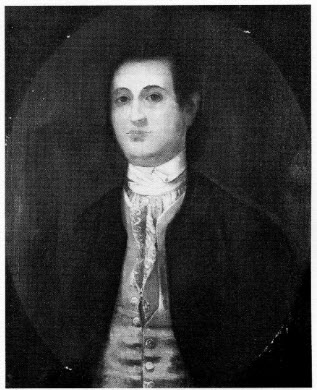

Colonel Thomas Ellison, artist unknown, Courtesy of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site.

Colonel Thomas Ellison, artist unknown, Courtesy of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site.

As relations with England deteriorated, he wrote of the city's response, legal and extralegal, to trade restrictions, such as the Stamp Tax and non-importation agreements. Once the war broke out, communication between Thomas Ellison, Jr. and his New Windsor relatives stopped - at least there are no extant letters - until 1787 when their correspondence resumed.

During the war, John and William Ellison in New Windsor and their father, Thomas, Sr., until his death in 1779, retrenched and focused their business activities locally. In addition to their various land investments, the presence of the Army in New Windsor at various times during the war must have provided another economic resource for them.

From the flour that John Ellison supplied, to "100 big trees" for the fortifications at West Point, both John and William Ellison depended to some extent on the Army. Their land, along with others, was used for hutting the troops, timber cut from their woodlots supplied fuel, and their homes housed officers. George Washington stayed in Thomas Ellison Sr.'s house for a month in late June through late July, 1779 (William Ellison inherited the house on the father's death in 1779) and again from November, 1780 to June, 1781 while planning the Yorktown campaign.

The Colonel Thomas Ellison House by J.L. Morton. John Ludlow Morton (1792-1871), a member of the National Academy, shows the waterfront house as it may have looked in June-July of 1779 when Washington made it his headquarters. The view looks south toward the north gate of the Hudson Highlands with Butter Hill (now Storm King Mountain) rising on the right and Breakneck Mountain on the left. The house was destroyed in the 19th century. Morton married Emily Ellison, a great-granddaughter of Colonel Ellison. Courtesy of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site.

The Colonel Thomas Ellison House by J.L. Morton. John Ludlow Morton (1792-1871), a member of the National Academy, shows the waterfront house as it may have looked in June-July of 1779 when Washington made it his headquarters. The view looks south toward the north gate of the Hudson Highlands with Butter Hill (now Storm King Mountain) rising on the right and Breakneck Mountain on the left. The house was destroyed in the 19th century. Morton married Emily Ellison, a great-granddaughter of Colonel Ellison. Courtesy of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site.

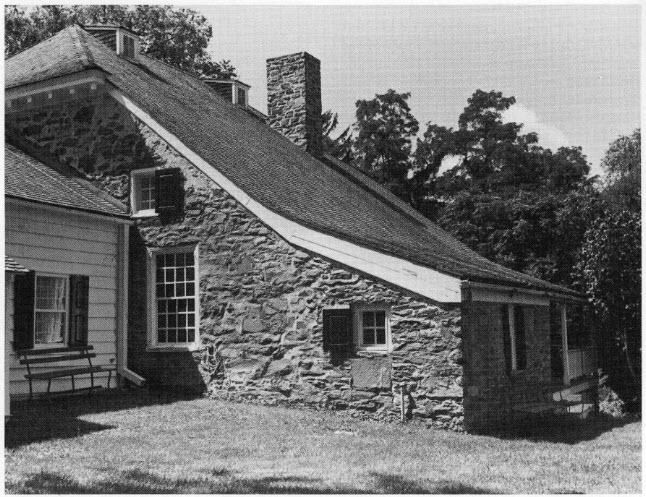

The John Ellison house became home to several Continental Army generals and their staffs, including Nathanael Greene, Henry Knox, and Horatio Gates. This house is now a New York state historic site known as Knox's Headquarters for MajorGeneral Henry Knox who billeted there on four different occasions in the war.

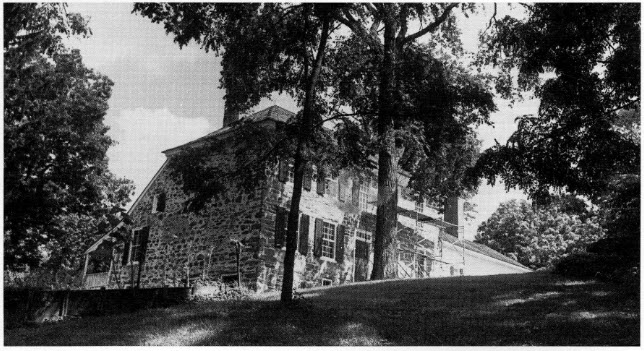

Two contemporary views of the 1754 John Ellison House, (Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site). A portion of the King's Highway from New Windsor to Goshen originally ran in front of the house.

Two contemporary views of the 1754 John Ellison House, (Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site). A portion of the King's Highway from New Windsor to Goshen originally ran in front of the house.

Beginning in June, 1779, Knox and Quartermaster General Nathanael Greene and others in Greene's department occupied three rooms for five weeks.

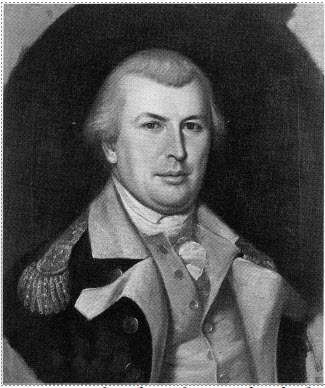

Major General Nathanael Greene by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy of Independence National Historic Park.

Major General Nathanael Greene by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy of Independence National Historic Park.

Knox used three rooms in the fall of 1779, two rooms for about eight months from November, 1780 to July, 1781 when the Continental Army's artillery park was located nearby, and one room for his final stay at Ellison's from May through September, 1782 before assuming command of the West Point garrison. Gates would subsequently use Ellison's for his headquarters.

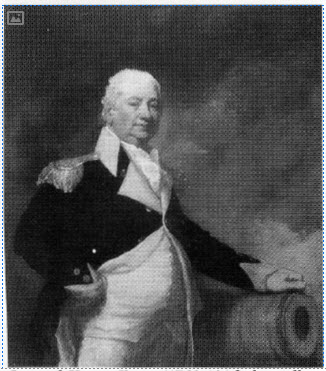

General Henry Knox (1750-1806) by Gilbert Stuart. Painted by Stuart c. 1805, a year before Knox's death. Deposited by the City of Boston. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

General Henry Knox (1750-1806) by Gilbert Stuart. Painted by Stuart c. 1805, a year before Knox's death. Deposited by the City of Boston. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In 1782 when Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering went in search of an appropriate hutting ground for the winter cantonment, he found it on land owned principally by John and William Ellison, Dr. Evan (?) Jones and Samuel Brewster. Pickering reported on his search to General Washington. From the east side of the Hudson River, his party consisting of Colonels Henry Swift, Henry Jackson, and David Cobb crossed to the Newburgh side and looked at six tracts of land. "Not satisfied with any of the ground," they went on until they came to the former artillery huts of 1780-81 used by Knox's artillerists "to view the Ellison's lands."

Going to the west through the woods, he found "an excellent grove of trees" that would be sufficient for hutting two brigades. Described as southward from Deacon Brewster's and on the road from Ellison's to the Little Britain road, this land became the hutting ground for the 1st and 3rd Massachusetts Brigades. Another brigade (the 2nd Massachusetts from the DeWitt map) could be placed to the rear of the artillery huts in William Ellison's woods, Pickering reported, and additional timber could be procured on the adjoining land owned by Jones.

It was also Pickering's task in 1782 to find housing for the officers, a challenging assignment as comfortable accommodations were scarce. The use of John Ellison's house was fiercely contested by General Gates and Dr. John Cochran, Director General of Hospitals, with each arguing his case to Quartermaster General Pickering. Cochran had stayed at Ellison's in December, 1780 and Pickering had built a "small place" for Cochran's servants and for his kitchen. Cochran was looking forward to taking up residence again, and indeed, had moved in.

Meanwhile Gates was temporarily using William Edmonston's down the road, as it had been promised to Major General Arthur St. Clair. There was no easy solution. Cochran refused to budge from Ellison's unless other quarters were found for him. Pickering knew of none except for Esquire Nicholl's, and Pickering reported " .. Esq. Nicholl does not chuse him for an inmate ... What shall be done? I will send to some houses in the Clove road to see if any can be found admitting of quarters for the director.”

Dr. Cochran was enraged that no quarters had been arranged for him prior to his arrival and ended a long letter to Pickering giving his side of the case, concluding he would give "any satisfaction you may demand, where Pen, Ink and Paper are not concerned." Gates took matters into his own hands and wrote directly to Washington informing him that he was without permanent quarters and that “.... Your Excellency's Dog kennel at Mount Vernon is as good a Quarter as that I am now in." Before another day passed, Gates had Ellison's and Dr. Cochran took quarters across the river.

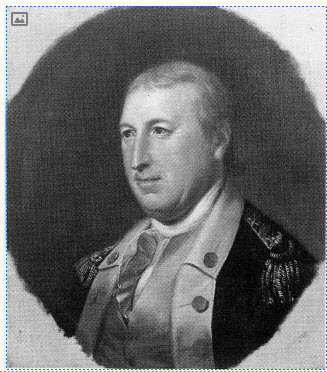

Major General Horatio Gates by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy of Independence National Historical Park.

Major General Horatio Gates by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy of Independence National Historical Park.

While the Ellisons were compensated for the Army's use of rooms in their house, there were probably other benefits, too, from housing officers. Certainly an element of prestige was associated with having Army personages at your house. The Ellisons joined Deacon Brewster, Squire Nicholl, Squire Belknap and other prominent people in the community whose houses were also used by the Continental Army. And unlike Trynte Hasbrouck who had to surrender her entire house for Washington and his official family to be adequately accommodated at Headquarters Newburgh while she lived elsewhere - and not surprisingly she reacted to the news in "sullen silence" - John and Catherine Ellison only gave up some of their rooms in their spacious house to the various generals and their staffs. "Hosting" Henry Knox and Horatio Gates may indeed have improved Ellison's standing in the community, for John Ellison's loyalties to the American cause have been considered suspect. Some have felt his position of leadership and prestige declined during the war and was not regained later because of what could at best be called his wartime neutrality.

Ellison's name was conspicuously absent from the 1775 Pledge of Association for the Town of New Windsor, and his sister Betsy was married to Cadwallader Colden, Jr., son of the former Lieutenant Governor (whose home in New York City was attacked by an angry mob) and a loyalist who served over a year in jail before being paroled. Citing Betsy Ellison's marriage to Colden, Jr., Dempsey, in Washington's Last Cantonment, states that the "Ellisons were known to have Tory leanings and connections," but that their prominence in the community saved them from harassment."

Before the war, John Ellison was an important figure in the community. He served as town supervisor five times from 1768 to 1774. During the war, from 1775 to 1780 he held no position, and, in 1781 he held a minor post as one of seven highwaymasters. In 1783 and 1784 he was one of two overseers of the poor, and in 1787 a collector.

If his loyalities were suspect, it was an adroit move on Ellison's part to have his house used by the military. At the same time, the Ellisons may well have shared in the good times the various officers brought to the house. During Knox's command of the Artillery Park from November, 1780 to July, 1781, he was joined at Ellisons by Lucy and their two small children. Lucy was 24 years of age, vivacious, inclined to stoutness like her husband, and both enjoyed parties.

According to local tradition, John Ellison's home was the scene of dinner parties and social evenings. At one party, given in honor of the Washingtons who were staying at the Thomas Ellison house, it is said a young French officer was so taken with three young ladies present that he wrote their names with his diamond ring on the window glass. The pane of glass is now in the collections at Knox's Headquarters.

From the few references to the Ellisons in the Knox's papers, it appears they got along well with their military guests. From Dobbs Ferry, Henry Knox wrote Lucy wondering if she were going to make any stay at "our friends Ellisons at New Windsor."

Providing wood and forage to the hardpressed Continental Army was an additional service - and produced some income for both John and William Ellison along with others in the community. John Ellison's lands provided timber for the army's use as early as 1777. Compensation was awarded him for 2000 cords of wood in 1777 and 1778, and for 4050 cords for 1779, 1780 and 1781.

In 1782, the General Hospital in New Windsor, formerly Knox's artillery park of 1780-1781, was of special concern to Quartermaster General Pickering who needed to provide firewood for this Army complex made up of 32 huts burning 45 fires. The local inhabitants who helped supply firewood in the spring of 1782 included William Ellison.

On March 7, he was paid $8 and 1/2 for two loads of wood, 8 1/2 cords, carried to the hospital huts. Again, on March 28, he was paid $72 for "carting wood" to the General Hospital. The Ellisons' nearby neighbors also provided services. Receipts are in Squire John Nicoli's name, whose house was located on the river near Murderer's Creek (the Moodna) for transporting sick to the hospital, receiving $1.00 in payment.

William Edmonston, whose land abutted John Ellison's, transported a load of provisions from Fishkill to the Flying Hospital, receiving $1.00. In August 1782, Benjamin Case, apparently in the employ of William Ellison, transported seven loads of sick soldiers from New Windsor to the General Hospital and was paid in money and a bushel of corn.

Once it was determined that the troops were to be cantoned in New Windsor for the winter of 1782-83, Pickering directed that repairs be made to the artillery huts to "make them more comfortable for the sick." Wood, straw and special provisions were needed "so numerous are the sick and so long will they remain there." A few days earlier he directed the woodcutters to cut wood on both the lands of John and William Ellison, near the hospital huts. Two weeks later, Pickering was able to assure Washington that every arrangement had been made on hutting the troops and that the sick in the General Hospital would be supplied with wood and straw.

Firewood was also needed for officers residing in private homes - for the Washington's headquarters at Hasbrouck's, for Gates at Ellison's, for General Howe at Brewster's, among others. According to Dempsey, 600 cords of wood were brought to Hasbrouck's. During the time General Gates was at John Ellison's, William Edmonston helped supply the wood.

It was always difficult to have enough forage for the Army's horses and exceedingly difficult at the Cantonment due to a severe drought of the previous year. Local inhabitants helped provide forage in the spring and fall of 1782. Pickering also tried to get hay by paying for it in salt, an item the farmers wanted. Washington spent part of his Christmas Day, 1782 writing a letter to Pickering, venting his wrath for the "bad state of affairs" in Pickering's department. Conditions were so bad, he wrote, that his own horses had been four days without a handful of hay and three of his horses without a mouthful of grain. Officers were not attending meetings at Headquarters, he wrote, because their horses were too weak to carry them.

General Gates took matters into his own hands and had his and his aide-decamps' riding horses pastured at William Edmonston's "to prevent them from Starving." In the note he wrote Pickering was enclosed Edmonston's bill which could be paid in bar iron, salt or cash, whichever was more convenient.

Gates left his command of the New Windsor Cantonment early to return to his home in Virginia where his wife was terminally ill. General Heath replaced Gates, assuming command by mid-April 1783 and quartered at Squire Belknap's in Newburgh. The Ellisons had seen the last of their military guests, at least officially. Colonel Walter Stewart, Inspector General to the Northern Department and former aide to Gates, wrote Gates in May (1783) giving his best wishes for the recovery of Mrs. Gates and telling him that his wife and her sister were "now at Camp" with him and "experience every attention from the good Ms. Ellison they could wish. "

At the End

“An extra ration of liquor to be issued to every man tomorrow to drink Perpetual Peace, Happiness to the United States of Independence and America.”

-- George Washington, General Orders, April 18, 1783

This winter encampment at New Windsor proved to be the final one of the Revolutionary War.

News of the provisional peace treaty arrived in late March, and Washington issued the cease-fire orders effective April 19, 1783.

Pickering's quartermaster department began preparing for the Army to leave. Furloughs were drawn up, surplus army equipment disposed of, and restitution made to those whose property had suffered damages during the Army's stay. There were also many complaints against the Army. Stolen fence rails had to be replaced at the Reverend Close's. A Mr. Hopper complained that he was being kept out of the hut built near his house because Lt. Crane refused to turn it over to him. General Howe's staff was burning too many fires at the general's former headquarters at Brewster's house, a situation Samuel Brewster termed "abominable." Benjamin Walker, an aide to Washington, requested Pickering to get an old tent for "an old faithful soldier" who had served in company and could get work in Newburgh but needed a place to put his family. "It is a deed of charity to lend it to them till the poor fellow can make some other provision," Walker wrote. Seemingly, there was a myriad of details to attend to as Pickering dismantled the sinews of war built up over eight years.

Many goods were sold privately to various Army personnel as they prepared to leave and members of the community. The first of four large public sales took place on May 26 at 4 PM with "upwards of Ninety dragoon horses in good order with their saddles and bridles."

The actual furloughing of troops was effected in June without incident. A small contingent remained for Washington did not quit Hasbrouck's until mid-August. Some of Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering's department also stayed on, selling equipment and settling accounts well into 1784. Arrangements had to be made to continue pasturing the horses needed by Headquarters and Pickering's staff. David Wolfe, Assistant Deputy Quartermaster General wrote Pickering in July that Mrs. Hasbrouck's meadow was being used, and "This good lady has not sent for her money and consequently remains unpaid ... " In August payments were made to her, and to Samuel Brewster and William Smith whose meadowland was rented to August and to October, respectively. Samuel Wood and John Ellison were also to be paid $120 and $70 respectively for their meadow in August.

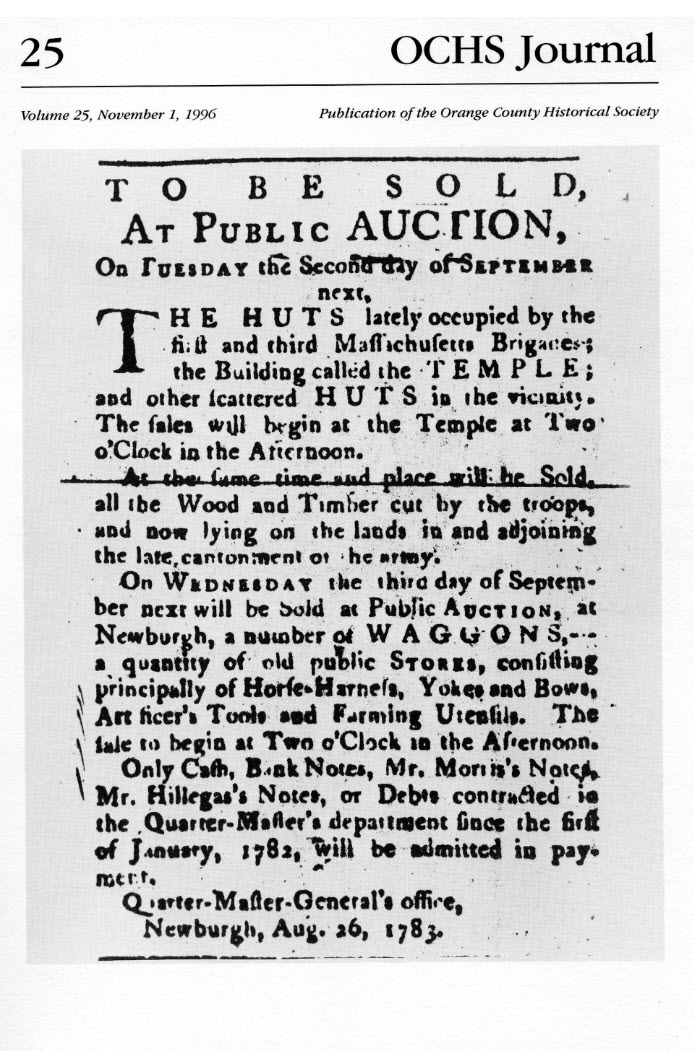

Two public auctions took place in the fall. The New York Packet announced an auction of huts of the 1st and 3rd Massachusetts Brigades, the Temple building and miscellaneous huts and all the unused wood and timber cut by the troops scheduled for September 2 at the Cantonment's Temple Building. The following day, wagons, tools, harnesses and various equipment and sundry public stores were sold in Newburgh.

Cantonment Auction Notice of the sale of buildings, goods, etc. The New York Packet, August 1783.

Cantonment Auction Notice of the sale of buildings, goods, etc. The New York Packet, August 1783.

David Wolfe's Daybook records payments received by his department's sale of Army goods from April 15, 1783 through the following March. Of approximately 200 entries involving sales, close to one-quarter were receipts for goods, principally horses, sold to officers and staff as they prepared to leave the Cantonment. The remainder were for goods - huts, equipment, batteaux, tents, blacksmithing items - purchased by civilians.

Robert Boyd, Jr., purchased some huts, Deacon Samuel Brewster bought a whole line of huts near his house, and William Edmonston paid $12 for a cow left at his place the year before. There are no sales receipts to John Ellison. Brother William, however, purchased a Franklin stove and a spar for a pettyauger (sic) ie. pirogue, making final payment in April, 1784. By this time, the Army had long since departed. The former Lt. Benjamin Gilbert was back home in Brookfield, Massachusestts prior to settling in Otsego County. Storekeeper John Currie at Ellison's had dissolved his partnership. The Ellisons themselves and the community were adjusting to peacetime conditions. And the Cantonment, itself; much of it decimated woodlots, would slowly revert to meadow and farmland.

Next Issue of Journal!

The Next Issue of the OCHS Journal is now accepting articles for consideration.

Authors

More guidelines for authors

Classics from the Journal

NEW!! General Richard Montgomery - Hero of Two Nations

by Marc Newman

NEW!! Joseph Brant and the Battle of Minisink

by Donald F. Clark

NEW!! John Hathorn - American Patriot

by Richard W. Hull

The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part I

by Michael S. McGurty

The New Windsor Artillery Park, 1780-1781 - Part II

by Michael S. McGurty

Orange County Militia During the American Revolutionary War

by Alan Aimone

George Washington's Masonic Activities in Orange County

by Andrew J. Zarutskie

Prisoners of War in Goshen

by Harold J. Jonas

John Robinson of Newburgh

by Margaret V. S. Wallace

The Battle of Fort Montgomery

by Donald F. Clark

Role of Regional Revolutionary Women

by Michelle P. Figliomeni

Robert R. Burnet (1762-1854)- The Last Continental Officer

by Alan C. Aimone and Barbara A. Aimone

The Revolutionary Soldier in Washington's Army

by Edward C. Cass

Technical Communication in the Amercan Revolution

by Carol Siri Johnson

New Windsor Cantonment

by E. Jane Townsend

Sidman's Bridge

by Kenneth R. Rose

Corridor Through the Mountains

by Richard Koke

Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck and "The Sybil"

by Amy Kesselman

The Store at Coldengham (1767-1768)

by Jay A. Campbell